Will Holman on the intersection of Engineering and Aesthetics with Evan Roche and Harrison Tyler

In 1981, Tracy Kidder won the Pulitzer Prize for The Soul of a New Machine, which profiled a group of engineers at Data General racing to put out a new mini-computer. The book became a foundational brick in a hacker mythos that has now built a culture more powerful than anyone could have imagined back then.

Once technology emerged from the damp, beady-eyed basement of Kidder’s book and landed in everyone’s pocket, all bets were off. Engineers became rock stars, sitting for lavish profiles in serious magazines and planning corporate campuses that would make presidents blush. But Kidder, in his year embedded with the team, saw through the cutthroat business tactics. “Engineers are aesthetes,” he said, years later, in a piece in Wired magazine. “They want technological symmetry.”

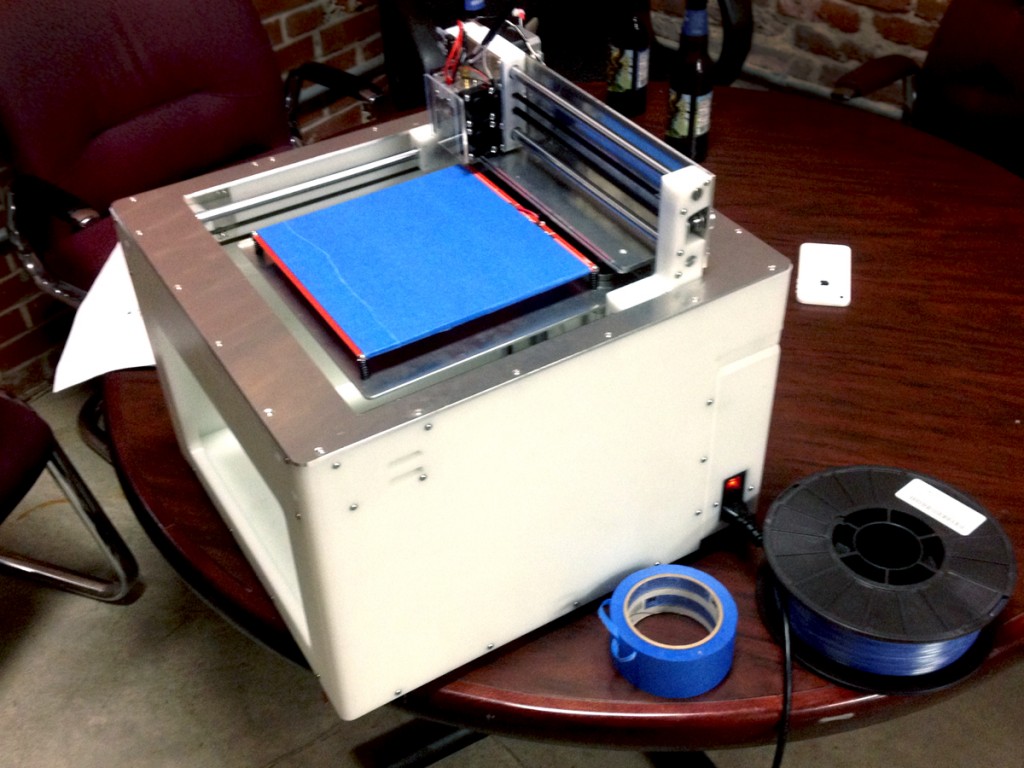

Evan Roche, 22, and Harrison Tyler, 23, are two-thirds of Jimmi Research, a project that sits squarely (and searchingly) at the intersection of engineering and aesthetics. Together with Lucas Haroldsen, 24, they designed and built a 3D printer in 2014 for their senior thesis project at the Maryland Institute College of Art. Conceived on top of open-source software, machined at MICA’s dFab studio, and populated with parts from all over the Internet, the Jimmi Research printer is in itself a portrait of our time.

The hardware business is littered with insurgent upstarts challenging the behemoths that currently dominate our phones, screens, and eyeballs. But the Jimmi crew is no dorm-room startup racing towards a stock offering; they see their machine as just a tool for asking questions.

“We all majored in inter-disciplinary sculpture,” they told me recently over drinks. Growing up in Vancouver, British Columbia, Roche was fascinated by car design, but ultimately found the idea of art school more appealing. He started MICA in 2010 as a painting major. “I was just figuring stuff out,” he said. “But I wanted something not so career-specific.” For Tyler, attending an arts magnet high school in Lake Worth, Florida, the initial interest was industrial design. But, struck with the absurdity of deciding a career path at 17, he too drifted towards generalism. Throughout our conversation, the two of them batted ideas back and forth, Roche playing the laconic straight man to Tyler’s amiable intensity.

At MICA, both found the sculpture program gave them the freedom to explore their interests instead of being handcuffed by discipline. The dFab lab, which opened in 2013, gave Roche and Tyler a chance to experiment with new technological territory that was evolving as rapidly as their ideas. They were among the first students to take Professor Ryan Hoover’s Introduction to Digital Fabrication, a survey course that taught the basics of CNC milling, laser cutting, and 3D printing. “I think that class was just perfectly positioned to draw us in,” Tyler said.

Hoover and the former dFab lab director, Andy Ta, took the Jimmi Research team under their wing. Ta had been giving a series of at-cost workshops on how to build simple RepRap printers; Hoover was experimenting with bio-printing at Baltimore Underground Science Space (BUGSS).

“[Ta] was an awesome force to have at MICA,” Tyler said. “But right when we had started making our machine he took a job at Rice University.” Tyler and Haroldsen pooled their money in December, 2013, and built their own simple delta-style printer based on open-source plans.

“It didn’t work very well at all. We realized we had to switch it up and design something way different,” he said. In January, with Ta off to his new job and graduation looming, they asked Roche to join their efforts.

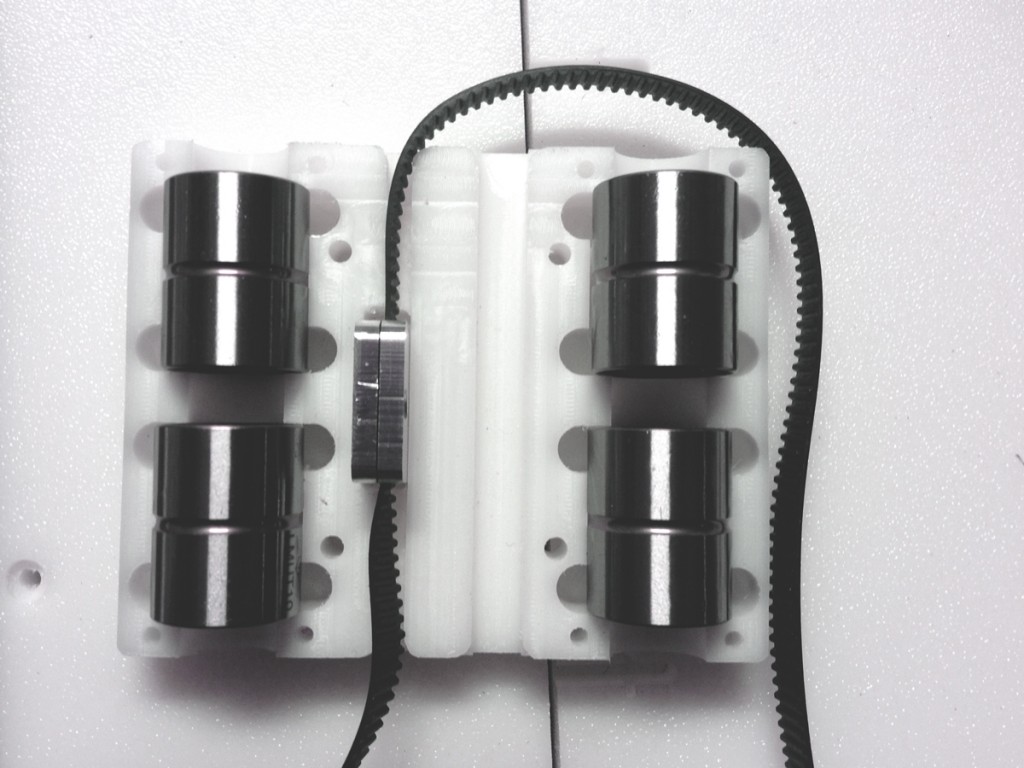

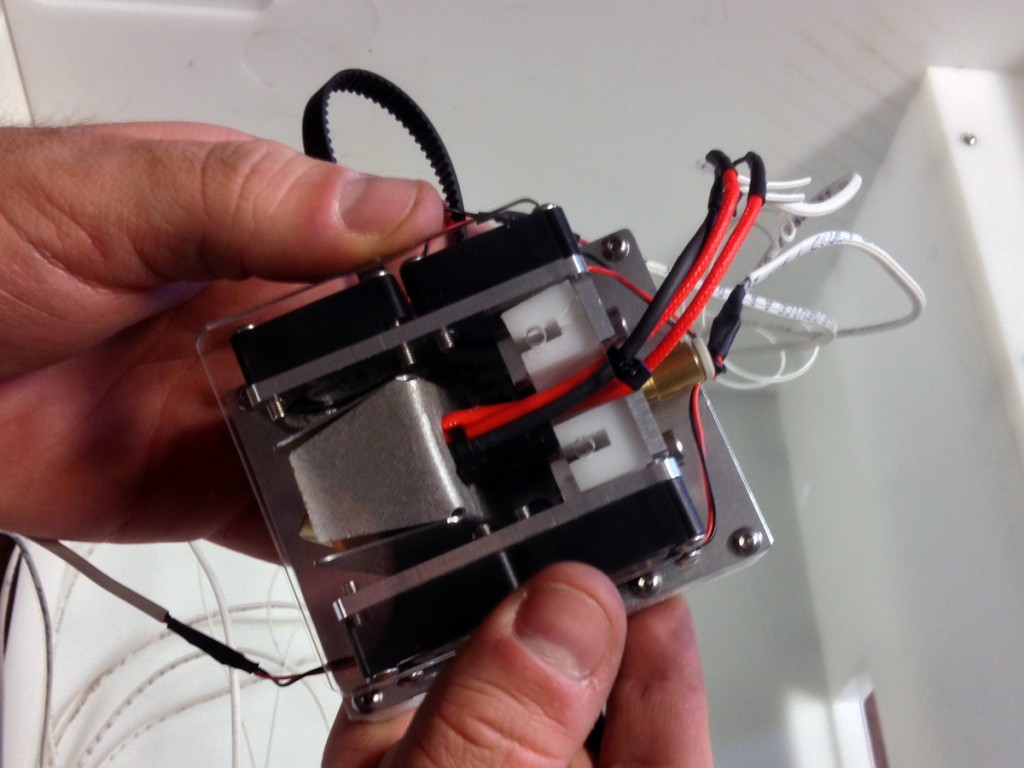

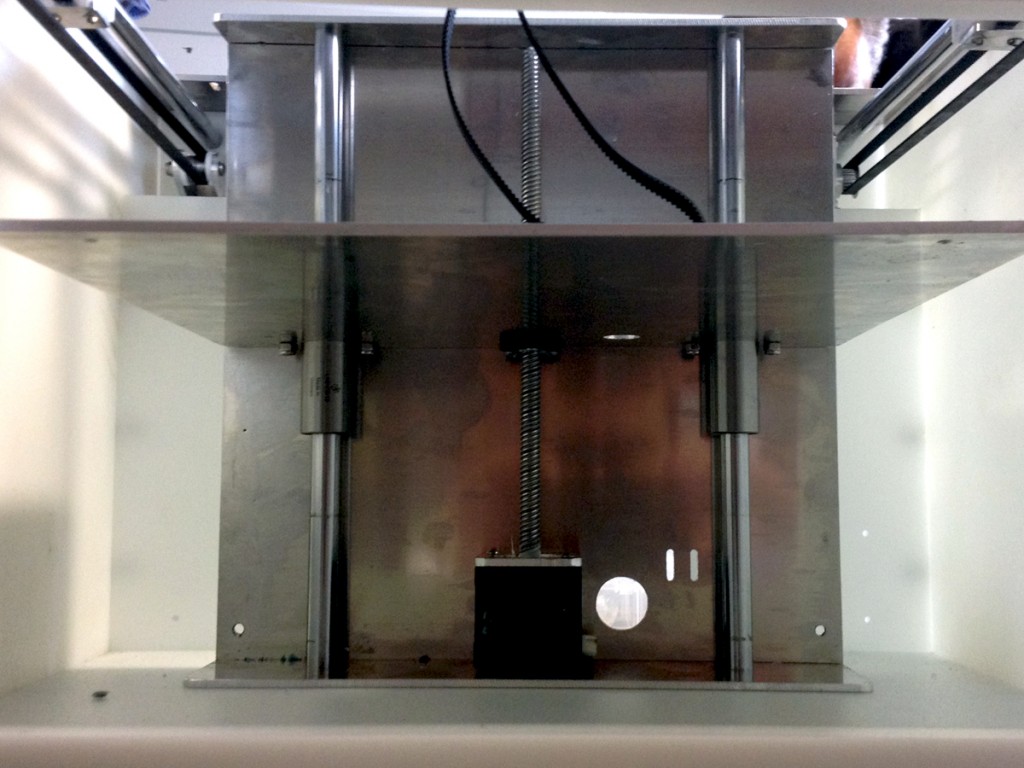

“Lucas made the bed. I made the carriages. Harrison made the frame,” Roche recounted. They designed everything in Rhino, then met up, combined their files, discussed, and edited. The process was iterative, but rapid, driven by the wealth of RepRap knowledge online.

“You get into deep problem solving,” Roche said. “You change one thing to suit your needs and the thing becomes a great big problem, like a Rube Goldberg machine.”

Besides the engineering challenges, the team was acutely aware that they were roaming on unexplored ground, entering a field broken wide-open by the expiration of key patents in 2013.

“Unlike any other fabrication tradition we learned [as sculpture majors] it had very little tradition to stand on,” Tyler said. “We were building that tradition ourselves.”

By May, they had a working machine. For their thesis show, Haroldsen came up with the idea of naming the project Jimmi Research, after a Japanese Hank Williams impersonator named Jimmie Tokita.

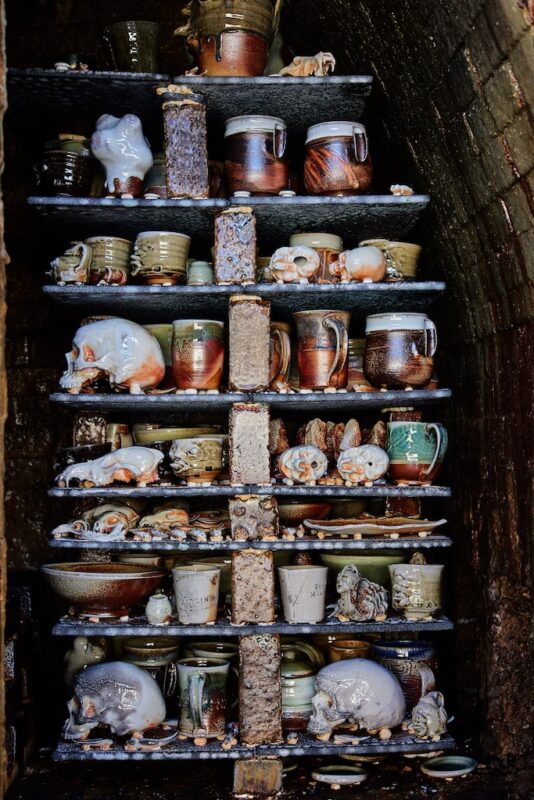

“He [represented] the ultimate visitor, something virtual,” Roche said. “It was miscommunication, or a misunderstanding, that we found value in.” They viewed the printer as a tool for purposely mis-translating form, pushing on the boundaries of architecture, design, and sculpture.

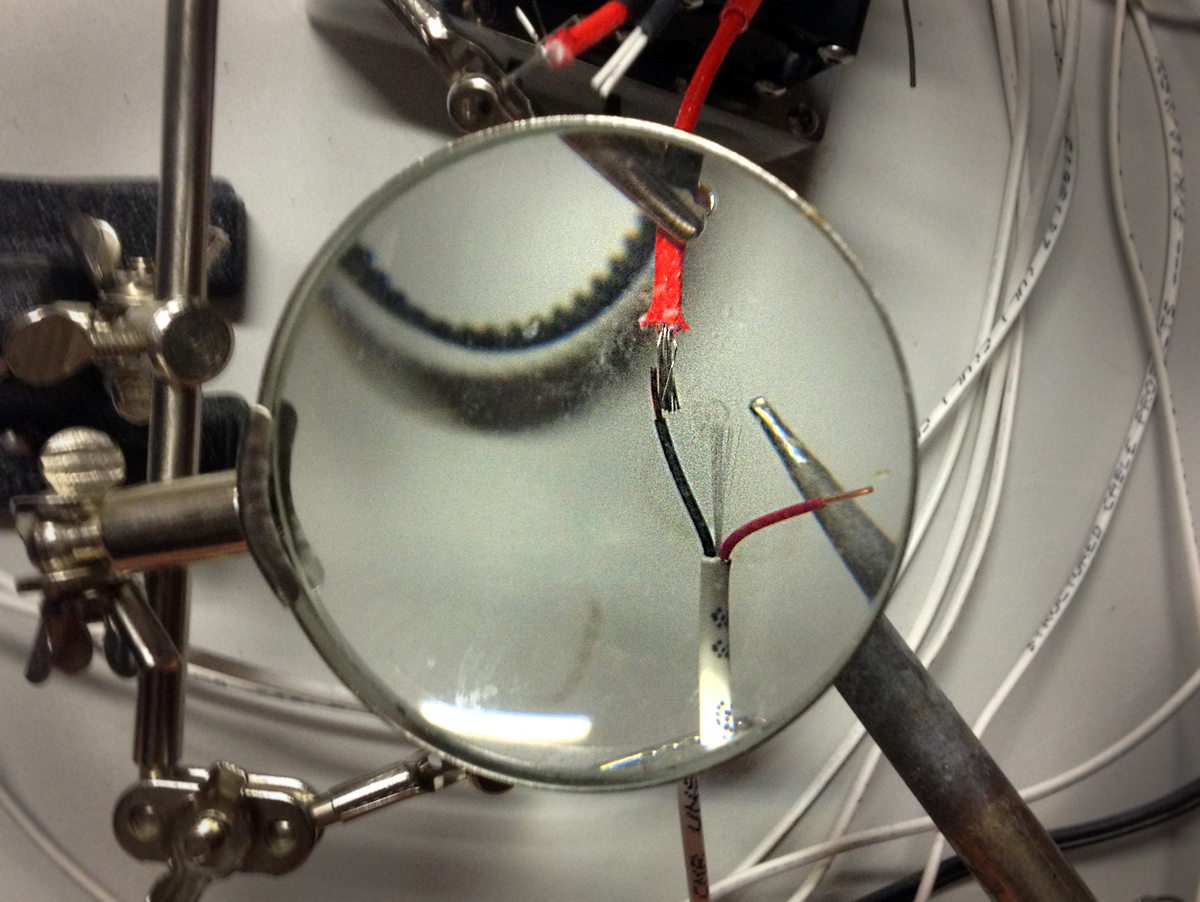

The first iteration of the machine didn’t even use plastic filament, the most common material for 3D printing. Instead, the team adapted a syringe-based extruder first designed by Hoover into a platform for printing nearly any viscous material. “We weren’t concerned with print quality at all,” said Tyler. “We were printing oil paints, adhesives, caulk, ceramics. Totally experimenting.”

Their thesis show, a collaborative effort with several other artists, took the form of a chaotic design studio, scattered with works-in-progress. Each artist was confronting new ways of looking at space and new ways of manufacturing form. “That was a big splatter of parts I’m now picking up and collecting and giving more meaning to,” Roche said.

Soon after graduation, Tyler and Roche were hired on as shop technicians at the dFab studio, and Hoover asked them to teach a build workshop. The classes – two held at MICA, one at Hopkins, and one at BUGSS – have become a way to both raise funds for further design research and a reason to keep improving the machine.

A few weekends ago, I took the latest build workshop. The other participants hailed from D.C., western Maryland, and New York, with design, engineering, and art backgrounds. We were presented with a table full of parts and an Ikea-style assembly booklet, full of wordless exploded diagrams. Roche and Tyler didn’t stand up and lecture like a traditional class; instead they patiently worked the room providing tech support and encouragement.

I had no experience with electronics, soldering, or 3D printing, and was apprehensive about the process. Nonetheless, after a hectic weekend cut short by a snowstorm, I had a dull white box plugged into my laptop. It took me a few more days to get it printing, but there was a moment of pure euphoria when the extruder lurched forward for the first time under my command. I had built it, and it was alive.

That’s exactly what Tyler and Roche were hoping I’d feel – the machine itself becoming almost irrelevant to a process of empowerment. In that sense, the workshops have become performances, a participatory ritual that pierces the veil of magic surrounding the technology and attendant hype.

“I like to think people think we’re in Tyvek suits with hairnets on and anti-static bracelets,” Tyler told me, laughing. “I want 3D printing to be demystified for people.” The machines, made by hand, circle back to the element of craft that first attracted Roche and Tyler to sculpture.

“It demystifies not only the 3D printer but all the things,” Roche added. “There’s more of a difference between the idea of a 3D printer and the making of it than the idea of a table and making it. People think it’s magic and it’s not. You make it with a drill.”

Future plans for the Jimmi Research project, much like its happenstance biography, are fluid. The team plans to continue holding more workshops, including outside of the Baltimore region. Since graduating, both have become more critical of the technology, which at this point has been largely used for printing plastic trinkets.

“Looking into the ‘maker movement,’ it was just so many useless things, Tyler said. “We want to move away from product development and work on an [accessible] material exploration console.” They are eager to explore 3D printing in other contexts, outputting unusual materials, choreographing performances, and creating videos.

Like their namesake, Jimmi Research is transliterating a foreign language, trying to tease out the aesthetic soul of these new machines. As part of an emergent subculture, they seem intent on upsetting the conventional hacker narrative, breaking out of the “maker” identity in pursuit of something more honest, more free, more weird. “We are defying the format,” said Tyler, grinding forward, one white box at a time.

Learn more at Jimmi Research dot com.