On April 12th, West Baltimorean Freddie Gray was arrested, manhandled, and packed into a paddy wagon. Amateur video of the scene shows him screaming, legs dragging limply on the ground. After undergoing surgery on his spine, he lapsed into a coma and died on April 19th. Protests began immediately. On April 25th, altercations between drunken Orioles fans and protestors spiraled into violence. Two days later, public transportation was shut down, stranding hundreds of school kids at Mondawmin Mall, a major transport hub. Bricks and bottles began to rain down on officers, and the situation spiraled into fires, looting, and widespread violence.

As I write this, on April 30th, the city is on a 10 PM curfew. A massive (peaceful) march has ended at City Hall, with thousands chanting for change. The Jones Falls Expressway, out my window, is eerily quiet, normal traffic noise replaced by the thwack-thwack of helicopter blades. National Guardsmen line the streets. The Orioles played the White Sox to an empty stadium yesterday. The city feels like it is on a war footing.

I write for Bmore Art about design, architecture, and urbanism, which, at their core, are all political issues. The popular press doesn’t often think of them that way, instead treating them like a set of passing fancies trotted across our screens as an amusing diversion. Oh, do tell — what color of iWatch Band will #trending this holiday season? But as the drumbeat of national attention hammers on our heads like the downdraft of police copters, Baltimore the butt of John Stewart barbs and Rand Paul racism, it bears explaining that what happened to Freddie Gray was not a set of rogue actions — it was a designed structure of exclusion. And as those distant voices mock this town, remember that these structures, though not as strong as they once were, still stand in Chicago, St. Louis, Buffalo, Cleveland, Oakland, Detroit, and elsewhere.

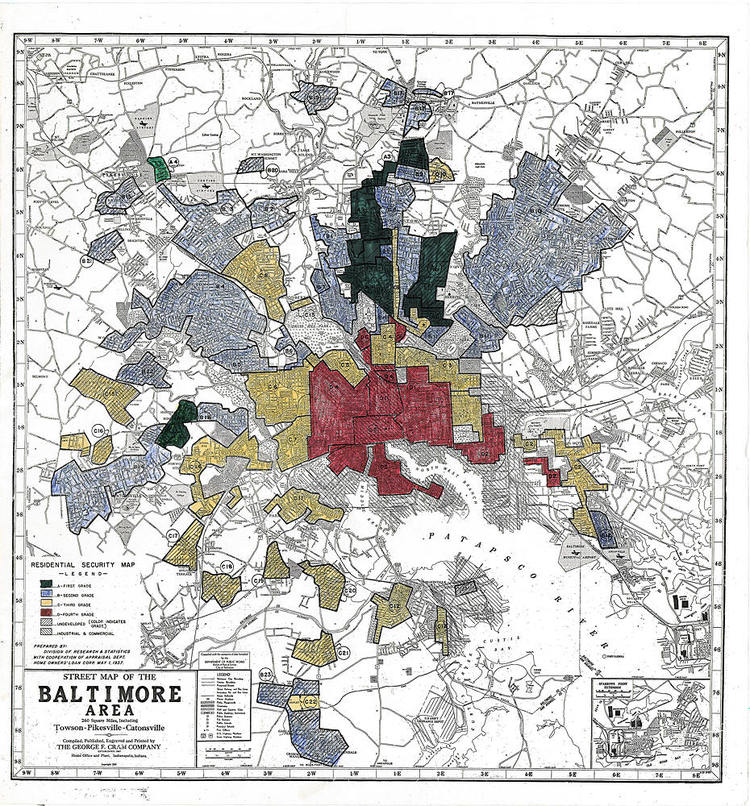

Between 1870 and 1900, Baltimore’s population doubled to 500,000, swelled with Confederate war veterans, Eastern European immigrants, and southern African-Americans looking for work in the shipyards, railroads, and steel mills. Coinciding with a national recession, which put a crimp in housing prices and supply, this period sowed the seeds for a century of housing segregation. In an era when most mortgages were provided by ethnic savings-and-loans associations, most African-Americans were denied access to credit, keeping home ownership below 1%. Official segregation ordinances were passed in 1910, preventing even those with money from crossing racial borders.

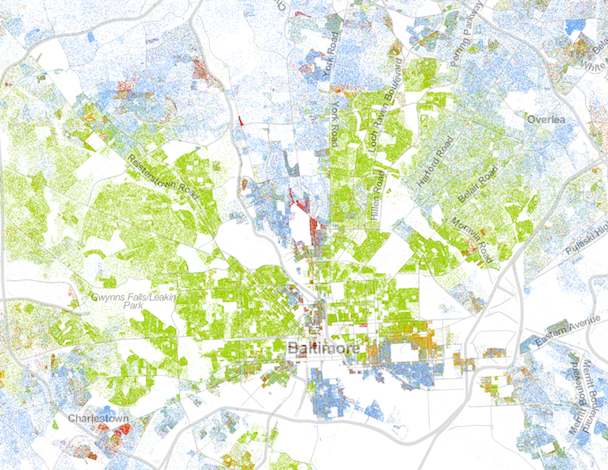

In 1917, that ordinance was struck down by the Supreme Court, which shifted segregationist practices to a de facto basis. In the 1930’s, the Federal Housing Administration tackled Depression-era housing problems in a starkly racialized manner, refusing to loan in “redlined” (African-American) districts. After World War II, the city aggregated “slum” blocks through eminent domain and built high-rise low-income housing, which concentrated poverty and reinforced de facto segregation. Only in 1968, with the passage of the Civil Rights Act, were these practices all explicitly banned, schools fully desegregated, and African-Americans given full access to credit mechanisms. But the damage had already been done, and Baltimore remains one of the most segregated big cities in the United States, with a dissimilarity score of 64.3 (anything over 60 is considered remarkable).

However, the striking down of segregation ordinances and the passage of the Civil Rights Act didn’t end exclusionary practices – it merely pushed planners, architects, and politicians to more creative ends. 99% Invisible, a podcast about design, covered these methods in an episode from 2012 entitled The Arsenal of Exclusion. Sam Greenspan interviewed Daniel D’Oca, an urban planner with a New York-based firm called Interboro Partners. On a field trip to Baltimore, D’Oca outlined a book he was working on and used the Baltimore neighborhood of Guilford as a case study for legal methods of segregation.

“Baltimore was once to the invisible wall building industry what Detroit was to the automotive industry—an innovative workshop where creative minds worked to think up, invent, test out, and ultimately export methods of exclusion,” D’Oca said, as he and Greenspan drove north on Greenmount Avenue from 33rd street.

On the east side of the street lies Waverly; on the west, Guilford, sequestered behind a stone wall and insulated from the street by a shallow block of rowhomes. In a 2-mile stretch of street, there are only two crosswalks. Most streets in Guilford are one-way out to the east, both preventing entry from the undesirable side and ejecting intruders who find their way in. One generally has to enter from the west side, which butts up against Hopkins. Street parking in Guilford is permit-only; in Waverly, it is free to anyone. All of these design elements, perfectly permissible by law, combine into an invisible architecture of exclusion. Post-governorship, Martin O’Malley landed in Homeland, one neighborhood north of Guilford, taking his gilded place in the hierarchy.

Public transportation followed a similarly disheartening trajectory – from a democratized, low-cost system of widespread streetcars to a consolidated bus system that is plagued with problems. Cities with high-density public transportation, like New York, exhibit much greater racial integration and job mobility. In Baltimore, resistance to public transportation is usually couched in language about crime, parking, and fiscal responsibility, code words for preventing far eastern and western residents from reaching the city center. That reasoning explains why, 23 years after the Light Rail was built, there is still no stop in Ruxton and residents of Canton are fighting Red Line expansion tooth-and-nail. Hopkins, MICA, and even University of Maryland all run private buses in the city, unwilling to subject their students to the vagaries of the public systems.

Racial segregation goes hand-in-hand with income inequality. Destruction of school districts, decent housing stock, and middle-income blue-collar jobs has stretched the divide between the very rich and those just getting by to historic highs. Income inequality, measured as the ratio of the top 5% of earners to that of the bottom 20%, is 12.4 in Baltimore, 10th out of the largest 50 cities in America. From 1950 to 1995, manufacturing employment dropped from 34% to 8%, replaced largely by service-sector jobs in health care, hospitality, and food service. Eight of the top ten employers in Baltimore are hospitals, which is a microcosm of the inequality picture. Hospitals provide a (relatively large) amount of highly-paid positions for doctors and administrators; a smaller number of middle-class jobs in nursing and clerical work; and a vast bottom layer of janitors, aides, food-service workers, and technicians that work on an hourly basis.

Today the Baltimore City population is majority female, African-American, with a median income of $40,800 and a 26% college degree-attainment rate.

Combined with the historical factors outlined above, this has broad knock-on effects throughout the city economy and educational system. Broadband penetration hovers between 20% and 40%, well below national leaders in that area. City schools are doing poorly, and have been doing poorly for nearly a generation. The city contains at least 16,000 vacant homes, some of which are being demolished and cleared for developers in a manner reminiscent of the mid-century eminent domain battles. African-American neighborhoods are still subject to what has been deemed “The Segregation Tax“, a set of market forces that conspire to depress home values and appreciation rates vis-a-vis their white counterparts.

A century after the first racial covenants, we are reaping what has been in sown in Baltimore. Freddie Gray went to one of the marginally brighter lights of the city high schools; the one closest to the scenes of Monday’s violence just saw its former principal sent to jail on an appalling set of corruption charges. 3 in 4 police officers don’t live in the city limits, and act like an occupying force. Mr. Gray’s neighborhood, Sandtown-Winchester, lags in just about every indicator of community vibrancy.

Baltimore Chop, a longtime local blogger, outlined some of these problems in a recent series of posts A City That’s Hard to Love. He writes: “The time for thinkpieces, hot takes, and scolding Tweets is not today. Even inside the city there are those who would be quick to claim the moral high ground. But in the city of Baltimore there is no moral high ground and there never has been . . . If those cops aren’t indicted and jailed things will certainly get worse before they get better. You may have your opinion about the way things ought to be, but unless you’re living under a curfew this week we don’t want to hear it. We’re not living in the world the way we think it should be, we’re living in the world the way it is.”

This is the story of our city, writ now in blood, sweat, and fear. Most of the mainstream media is focused on the sensational: militarized instruments of state terror deployed in the streets of a major American city for the first time since the Rodney King riots of 1992. But the true story is a darker Faulknerian tragedy, the sort of intimate, relational racism enabled by an architecture of exclusion that makes it easy to self-segregate. It would do well for us all to remember that those unseen walls keeping others out also hem us in.

Design is a political act; it can’t raise Freddie Gray from his grave, it can’t indict those six cops, it can’t calm the anger of a quarter-million unfairly dispossessed, but it can pick apart the culture that got us here, brick by invisible brick.

Once the cameras have gone, and the helicopters have landed, let’s get to work.

Will Holman is a writer, designer, and project coordinator for the Baltimore Arts Realty Company. His first book, Guerilla Furniture Design, is out from Storey Publishing in March, 2015. Follow him @Object Guerrilla on Twitter.

STRUCTURES OF EXCLUSION was originally published at Will Holman’s website, Object Guerrilla.

Top Image by Kris LaRosa.