Rowan Fulton on Coordinated Disregard, a Group Exhibition at Terrault Contemporary

The notion of “coordinated disregard” in art is appealing, because it suggests a harmony between chaos and order. One could argue that this balance is present in all artistic endeavors, however I think the notion is particularly appealing when paired with the wild, off-kilter works in the group show of the same name recently featured at Terrault Contemporary and curated by Amy Boone-McCreesh. While individual works tend to falter, what’s most compelling about this exhibit is the concession that even the most expressive works which seem unbound by any rules do indeed follow their own systems of logic, as well as the affirmation that these works represent both work and play.

Agnes Martin once said, “Behind and before self expression is a developing awareness, [called] ‘the work.’” The strength of Coordinated Disregard as an exhibit is that it seeks to combine a number of playful mostly abstract works, which depend on some kind of self-imposed system (not unlike Martin’s own restrictive grids), a tight structure unique to each artist within which spontaneity and improvisation can occur. In this show, most find their system by diverging slightly from the familiar frameworks of painting and sculpture, producing interesting textural and chromatic effects through the use of unexpected media.

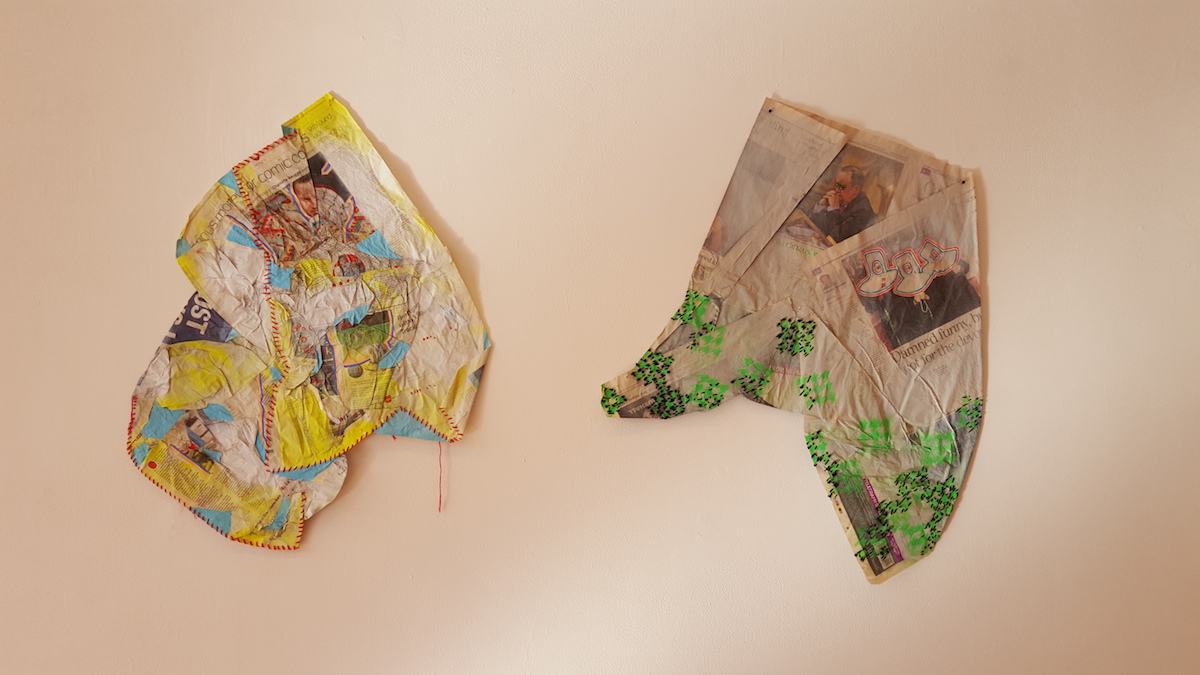

Elissa Levy creates mixed media pieces from newspapers. She starts by folding them, and then responds to the new, three-dimensional form using other materials and processes, including embroidery, marker, and gel pen. In the process, she brings the content of the newspaper, and its actual sculptural form, to an equal plane.

For example, in “Green Eyes” she outlines the grainy, photographed form of the headdresses of nuns using vibrant gel pen, and also employs a loose, free-form embroidery to fill areas of physical tension in the form of the newspaper. In other works, she introduces another three-dimensional element by shredding the paper into thin strips, which hang and waver, creating new kinetic shapes. All the while, Levy keeps the element of the newspaper and specific methods of drawing and cutting oddly constant, yet works intuitively within their boundaries.

The works of fiber artist Alicia Scardetta and painter Curtis Miller share an interest in partitioning vibrant visual content into segments. Perhaps the most rigid system on display here, Scardetta weaves yarn into tight rows, sometimes producing segments by building shapes of bold color, elsewhere by allowing areas of negative space to exist between rows.

Miller’s paintings, on the other hand, illustrate divisions through line and shape. In “Rotten Fruit and Broken Devices,” he separates these vaguely identifiable articulations of objects (I may see a pomegranate and a camera) in stacked, brick-like boxes. In the dark “cement” spaces between the “bricks,” we find even more tiny segments produced by painting delicate white lines; with both organic and geometric edges, they are reminiscent of colorful geographical borders and curiously glue together the fragments which compose this image.

Gabriel Luis Perez creates energetic, abrasive paintings, which utilize a limited yet rebellious lexicon of marks and materials, including spray paint, raw canvas shapes, safety pins, and (yes) glitter. One of these paintings, “Pinecone” catches my eye because of the sense of chaos created through a small semblance of order. Here, Perez builds up a densely layered surface using the canvas pieces and thickly applied gesso. Next comes expressive and seemingly random application of color by way of glitter and spray paint. Then he brings in order through pattern, applying square and circular dabs of white acrylic paint spaced equally apart, if a bit haphazardly. This single decision brings a certain harmony to this otherwise discordant mixed-media surface.

The sculptures of Randall Lear share the vibrant-highlighter-color sensibility possessed by Scardetta and Levy, as well as the thick geometric partitions present in Miller’s paintings, and therefore feel at home in this show. Strongest among Lear’s work are his two small sculptures, “Radiant Rind” (an abstract form evocative of a wedge of watermelon with all the fruit bitten off) and “A Misdirected Unmoved Magpie” (a box in which the negative space is activated with colorful string hanging across the center), which sit atop pedestals of differing heights in the center of the room.

These play with language and color, and connect to one another formally, as the movement of draped string inside “Magpie” echoes the hollowed semicircle smile shape created in “Rind.” I am conflicted, however, when it comes to the pedestals, which are painted in jarring lime greens and electric blues and patterns similar to those in his actual sculptures.

Compositionally, the inclusion of these pedestals makes for a nice show by scattering color throughout the room and giving a sense of visual balance (the other artists show exclusively wall-hung works), however when viewed individually, it is too easy to mistake the bases for components of the sculptures. When the color palette is so well integrated, the sculptures lose some of their power and begin to read as decorative hats on top of pillars.

Sometimes the works hanging in this show complement each other so well that they seem to reach across the gallery walls and embrace one another as friends. United by visual style and color palette, these works clearly belong in the same room. The aesthetic presented is quite popular right now, a deliberately-sloppy-fourth-grade-cool-expressionism which we’ve seen successfully in the work of local artists like Nicole Dyer and Dave Eassa, and the theme of the show and the collective grouping bolsters, where many individual works falter.

Although it’s colorful and playful, I find myself wanting more from most of the work presented. I am bothered by an overall insubstantiality or a deliberate casualism, which arrives after observing a given piece for too long. They’re likable, but these works could demonstrate more adequate levels of coordination and/or disregard and I am unsatisfied by their too early resolutions. Because each offers a system that is relatively loose and their marks are more or less obedient to familiar aesthetics, individual works can come across as small and experimental and I crave more rigor from them. However, this exhibit feels complete when viewed alltogether; lending more depth and subtlety as a group than they would possess individually.

Coordinated Disregard was on view September 4th-26th 2015 at Terrault Contemporary.

Author Rowan Fulton is a Baltimore-based artist and writer.