Pearls On a String: Artists, Patrons, and Poets at the Great Islamic Courts at The Walters Offers Models for Cross Cultural Enlightenment By Cara Ober

Sometimes the economic and social problems currently facing the United States appear to be inevitable, the result of a relatively new social experiment we call multi-culturalism. It is assumed that ours is the first time in history that so many different people from so many different places have tried to live together in one country and the inequality, racism, xenophobia, and violence that we face as a nation are a natural byproduct. However, history proves this to be untrue.

I was thrilled to visit Pearls on a String, the current exhibit at the Walters, because it confirms my conviction that art and culture make a pluralistic society stronger, kinder, and smarter. The exhibition presents three Islamic empires that flourished during historical periods of rapid innovation, focused around the stories of three dynamic individuals who elevated art, poetry, and craft. In their own way, each helped to build advanced societies where multiple religions, races, and nationalities were not only respected, but valued.

What’s particularly significant about this exhibit is the simultaneous occurrence of deep investment in the arts with stretches of peaceful prosperity. Although we can’t claim causality, in terms of the economic means to invest in the arts or the enlightened values it supports, the correlations within the three distinct Islamic societies (Mughal, Safavid, and Ottoman) presented in Pearls are consistent and present an obvious answer to so many of the ugly truths we currently face in the United States.

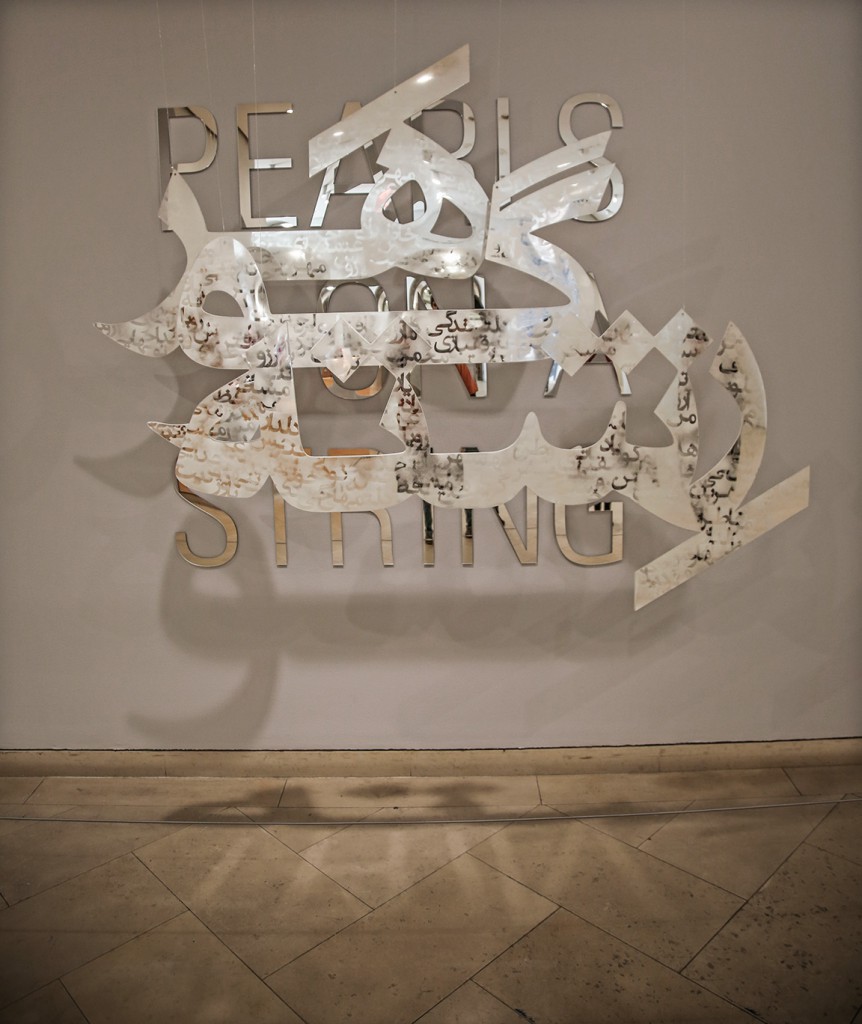

Original site-specific wall sculpture by Sara Shahabi depicting the title of the exhibit in English and in Farsi

Original site-specific wall sculpture by Sara Shahabi depicting the title of the exhibit in English and in Farsi

The exhibition’s title, “Pearls on a String,” is an Islamic phrase used to denote strength in plurality, the idea that one gleaming pearl is made exponentially greater when placed in context with others. This concept is reinforced even before you enter the exhibition in a site-specific wall sculpture by Sara Shahabi, a MICA graduate and graphic designer. The artist, based in Washington, DC, wanted to emphasize the importance of relationships between individuals in promoting artistic productivity, so her mirrored, laser cut surfaces of the Persian phrase “Reshte Gohar” (pearls on a string) are layered over the English version and embellished with additional phrases in Farsi.

As you enter the exhibition, you are greeted by architectural details, manuscript paintings, sculpture, luxury items, and textiles from The Walters’ own collection of Islamic art combined with borrowed items from the Victoria and Albert, the British Library, the Aga Khan Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the National Gallery and Smithsonian. Accompanying text is dense in this exhibit, but well worth your time, as it deepens your understanding of individual works and also how seemingly disparate works relate and coalesce.

Rather than presenting each Islamic empire holistically, curator Amy Landau focused on historical narratives surrounding one exceptional individual central to cultural production from each empire: the writer and historian Abu’l Fazl from the 16th-century Mughal court of Akbar the Great, the imperial artist Muhammad Zaman from the 17th-century Safavid court of Shah Sulayman, and Sultan Mahmud I, the 18th-century Ottoman ruler who lavishly patronized invention, art, and architecture. The exhibition’s title, Pearls on a String, refers specifically to these men: each is seen as a valuable contribution–a pearl–to a much larger, exponential sphere of influence.

Abu’l Pazl Presenting the Akbarnama to Akbar, from the Book of Akbar (attributed to Govardhan, ca 1600-03)

Abu’l Pazl Presenting the Akbarnama to Akbar, from the Book of Akbar (attributed to Govardhan, ca 1600-03)

In the 16th century Mughal court at Fatehpur Sikri, writer Abu’l Fazl (1551-1602) was instrumental in cultivating strong relationships between the emperor Akbar, a Muslim, and Hindu, Jain, and Christian communities in the area. In his life’s work, the illustrated manuscript, Akbarnama (The History of Akbar), the poet represents the emperor and his peers as a creative, multicultural community that engaged in a variety of intellectual and religious traditions.

Although the writer shaped the narrative aspects of the Akbarnama, the 3-volume work was a collaborative effort with painters and illustrators and produced some of the most dynamic and detailed manuscript paintings from 16th century India. The manuscript spawned a new age of art and production where borrowed motifs from Hindu and Muslim traditions are collaged elegantly together with elements of Jain and Christian symbols.

For example, in Abu’l Pazl Presenting the Akbarnama to Akbar, from the Book of Akbar, you see the emperor seated at the center with his legs posed like a Hindu god. This seemingly insignificant detail was a purposeful homage, extended to assimilate different cultures through visual communication. In addition to images from the Akbarnama, this first section Pearls included architectural details, carpets, and small sculptures–all which elegantly collage and synchronize the stylistic strengths of Muslim traditions with others.

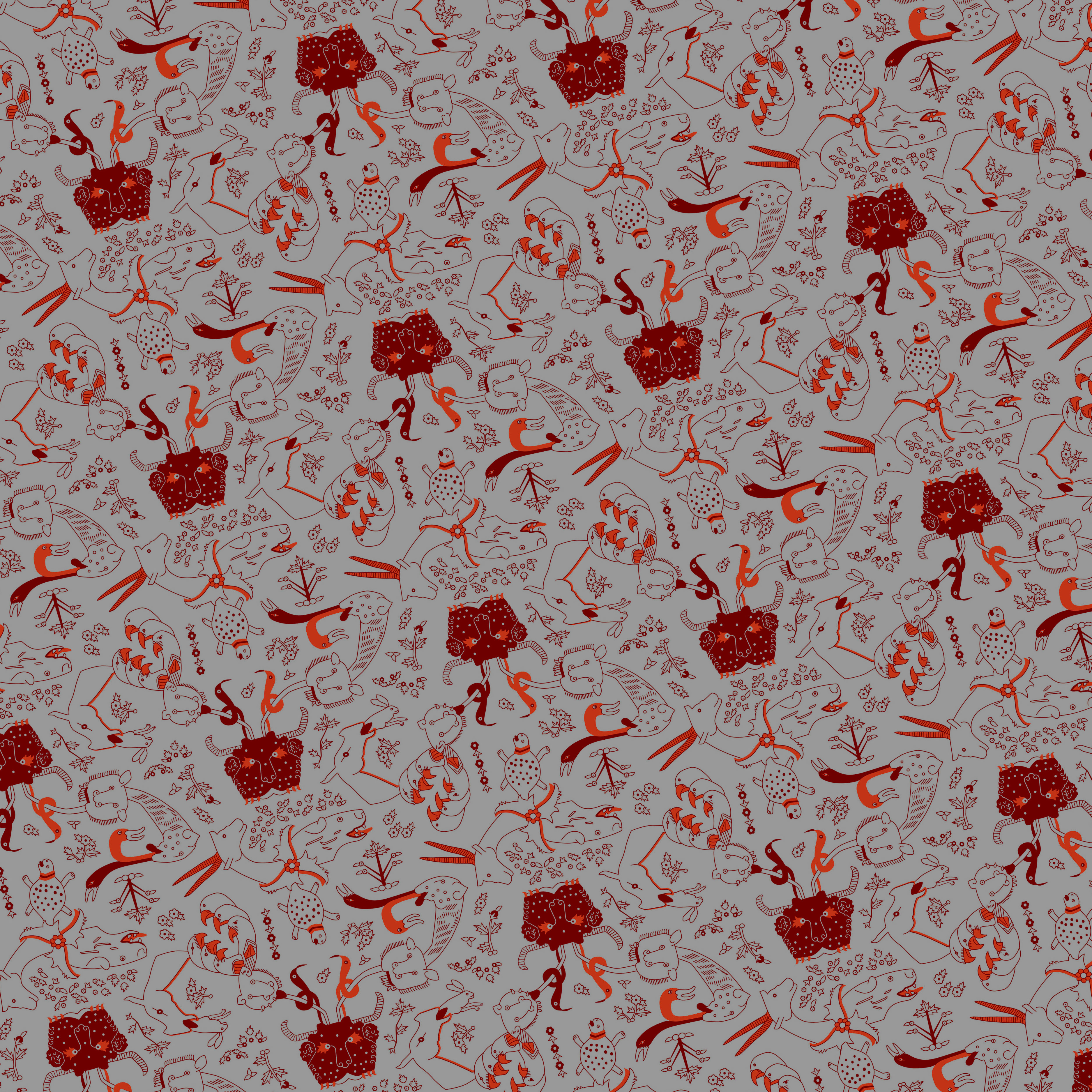

Pattern inspired by a fragment of a carpet with designs of fantastic animals, possibly Fatehpur Sikri, Mughal India, ca 1580-55

Pattern inspired by a fragment of a carpet with designs of fantastic animals, possibly Fatehpur Sikri, Mughal India, ca 1580-55

New products and styles reverberated from the original manuscript source, and The Walters design team took this a step further in creating original textiles based on a fragment of a carpet from Mughal India ca 1580-88. Used in small swatches to cover the upholstered seats throughout the gallery, with two additional designs for each of the adjacent empires, it was this contemporary iteration– an illustrative rendering of fantastic animals in floating designs–which truly galvanizes the spirit of the exhibit and places it into a modern context.

Not only was the pattern compelling from a color and design standpoint, it functions as a subtle mode of visual communication. Whether you understand what you are looking at or merely appreciate it’s bold combination of primal linear shapes, one gains a sense of the values of the culture it represents. Having this cloth be interactive and not under glass makes it even more compelling. (Please sell me a tote bag! I love this fabric.)

Young Woman in a Georgian Costume, 17th Century from the School of Muhammad Zaman

Young Woman in a Georgian Costume, 17th Century from the School of Muhammad Zaman

As you move into the second gallery, the fabric changes to a bird and flower motif to represent images common in Isfahan, Safavid Iran, from the 17th century. This section, devoted to the Safavid Court, centers around painter Muhammad Zaman ibn Haji Yusuf (active between 1670-1700), who completely “Europeanized” the paintings of his time.

Representing a place and a time where trade and education between East and West flourished, Muhammad Zaman’s paintings radically employ many of the contemporary techniques of Renaissance and European painting, but manage to combine them with traditional Persian miniature painting trophes in such a way that his audience accepted them. The Return from the Flight into Egypt, pictured below, shares more with Botticelli than many of the artists of Iran and was based on a similar composition by Rubens.

The Return from the Flight into Egypt

The Return from the Flight into Egypt

Zaman borrowed three-dimensional shading and modeling techniques, as well as chiaroscuro from European artists of his day. His new style called farangisazi (traslation: European style), was applied to Persian miniatures and poetic illustrations, as well as Biblical scenes and its success at the Safavid court is more significant than its artistic vision.

In a culture that included a network of elite and educated patrons, also merchants and travelers from all over the world, Zaman’s visual experiments represented the values of his day: an enlightened synthesis of East and West for a sophisticated and religiously diverse population, who embraced it.

Jeweled Gun of Sultan Mahmud I, with Writing Implements and Dagger

Jeweled Gun of Sultan Mahmud I, with Writing Implements and Dagger

The third and last section of Pearls centers around Sultan Mahmud I, the 18th-century Ottoman ruler who patronized luxurious items including art, architecture, and inventions. Straight out of Game of Thrones, Mahmud was a short, stout man with a congenital curvature of the spine. When he became emperor in 1730, expectations for his intellect and political prowess were low; he was believed to be easy to control by advisors in his court. However, Mahmud proved all who doubted him to be wrong and his reign, a powerful and purposeful force from 1730-54, was a pinnacle of peace and prosperity in the Ottoman Empire.

Rather than proving his power through war or aggression, Mahmud build vast libraries and commissioned lavish works of art and craft. He was able to build an image of a financially and militarily secure empire through art patronage and Istanbul was widely regarded as a modern cosmopolitan court poised at the crossroads of Asia and Europe.

Detail – Diamond Initials from Jeweled Gun of Sultan Mahmud I, with Writing Implements and Dagger

Detail – Diamond Initials from Jeweled Gun of Sultan Mahmud I, with Writing Implements and Dagger

One of the most innovative pieces in the exhibition is one of Mahmud’s most prized commissions: Jeweled Gun of Sultan Mahmud I, with Writing Implements and Dagger. Not only was the working weapon golden, it was encrusted with silver, nephrite, diamonds, emeralds, and rubies.

It also offered a number of secret compartments for a similarly embellished dagger and a writing set with multiple pens. It is unclear whether Mahmud wanted to communicate that the pen is just as mighty as the weapon, but the loving details, including the emperor’s blinged out diamond initials in a secret compartment at the butt of the gun suggest a playful cultured ruler who valued intrinsic beauty and clever ideas.

Although I had a very good public education (I scored a 5 on the World History AP Test – Thanks, Mr. Richardson!), I will admit that I learned very little, if anything, about historic Islamic cultures in school. Our current political climate, full of inaccurate and fear-mongering information, damages the cultural connections between Christians, Muslims, and Jews every day. Although Pearls on a String is an intelligently curated exhibition and a rare opportunity to view exquisite handmade historical objects, more importantly, this show successfully fills in some of the historic gaps in our collective memory.

The sophisticated objects on display in Pearls reflect the societies that produced them. They exist as proof that art and culture is more powerful than the fear that comes with embracing people from different countries and different religions. These objects, and the ideas behind them, show us how much all societies have in common and how much we owe to cultural ancestors from all religions. Pearls presents decisive proof to the exact opposite of what most of our current government leaders, who cut funding for the arts as extraneous and non-essential, believe: a culture that values and financially supports the arts is simultaneously powerful, prosperous, tolerant of all religions, and multi-cultural.

Author Cara Ober is founding editor at BmoreArt.

The Walters Art Museum will present Pearls on a String: Artists, Patrons, and Poets at the Great Islamic Courts through January 31, 2016. Free.

The exhibition was organized by the Walters Art Museum in partnership with the Asian Art Museum, and will be on view at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco from February 26 through May 8, 2016.