A couple of weeks ago, I was listening to a longtime educator describe the trajectory of her career. She summarized her years as a fledgling instructor in the early 1990s, invoking what might be called a typically abstract academic interest in American history – and then she paused. “And then I saw,” she said, “Mining the Museum.”

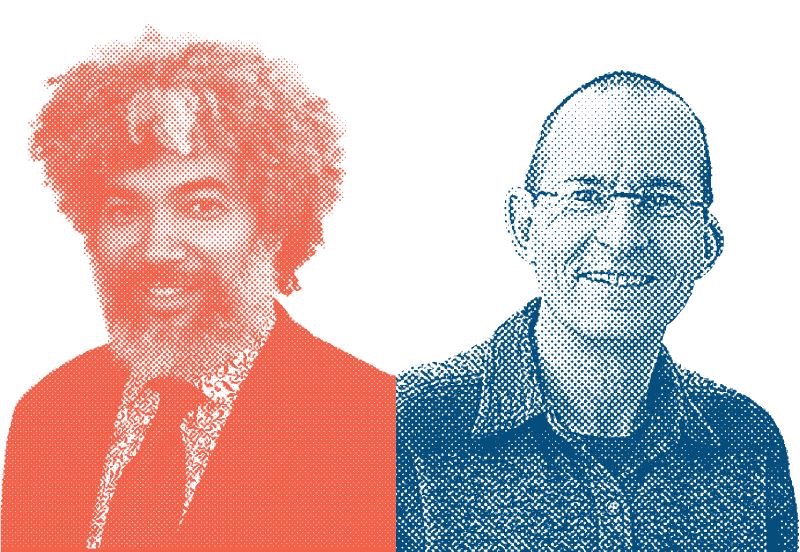

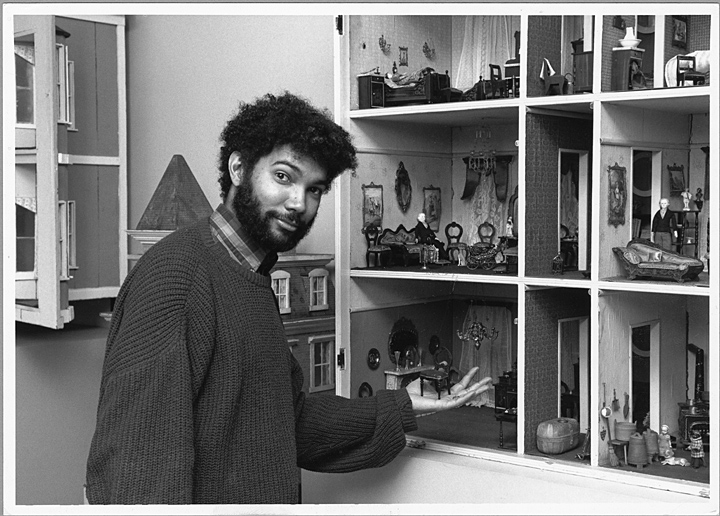

The influence of Fred Wilson’s seminal 1992 intervention at the Maryland Historical Society (now, the Maryland Center for History and Culture) is at once easily summarized and remarkably complex. Working with objects in the collection of the MHS, Wilson unsettled the museum’s comfortably white, upper-class narrative by juxtaposing silver repoussé vessels and elegant 19th-century armchairs with slave shackles and a whipping post. Texts, spotlights, recordings, and objects traditionally consigned to storage drew attention to the local histories of blacks and Native Americans, effectively unmaking the familiar museological narrative as a narrow ideological project.

The result was profoundly unsettling–especially given the eruption, a mere week after the show opened, of street violence in Los Angeles following the acquittal of four white officers accused of beating Rodney King. Sure, reactions varied, but they were almost always intense. Nancy Martel, the MHS’ education assistant, found herself unable to stop talking about Wilson’s work. Attendance at the museum surged. A 62-year-old retired dentist from Easton breathlessly exclaimed, in an exit survey, that the show “has the ability to promote racism and hate in young blacks, and was offensive to me!!” And the professor with whom I was speaking began to emphasize more ambitiously, in her work, the lives of African-American women, and the place of source documents and material culture in her research.