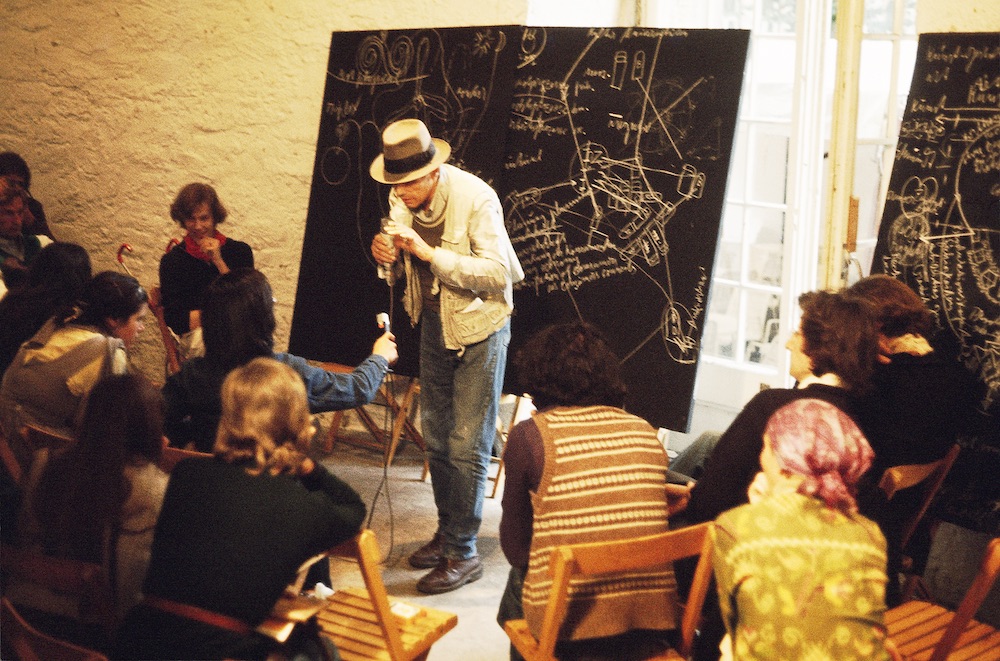

Jo Smail, an exceptional artist, thinker, and teacher who has been based in Baltimore since she left her native South Africa in 1985, is the subject of a retrospective, Jo Smail: Flying with Remnant Wings, that I organized for the Baltimore Museum of Art. The show opened in early March.

Neither Jo nor I ever imagined that a pandemic would interrupt the retrospective just weeks after it went on view. We have known each other since the late 1990s when I included her pink paintings—made after a 1996 studio fire destroyed decades worth of her previous work and loaded with vulnerability despite their minimal compositions—in a show at the University of Maryland, College Park. In a sense, the BMA retrospective was decades in the making, as I observed and admired the inventiveness and optimism of Jo’s ongoing practice. To have the physical encounter at the museum with the gathering of twenty-five years of her work suspended so suddenly and indefinitely was difficult, to say the least. And yet, as always with Jo and her work, there was a consolation.

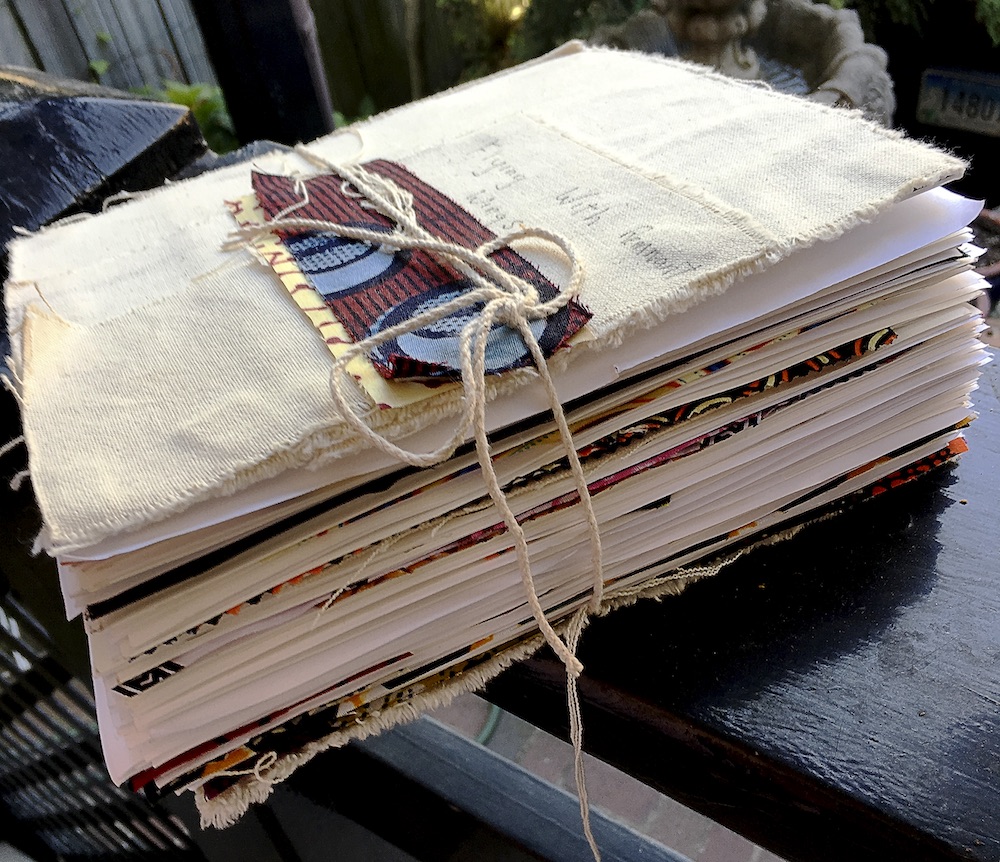

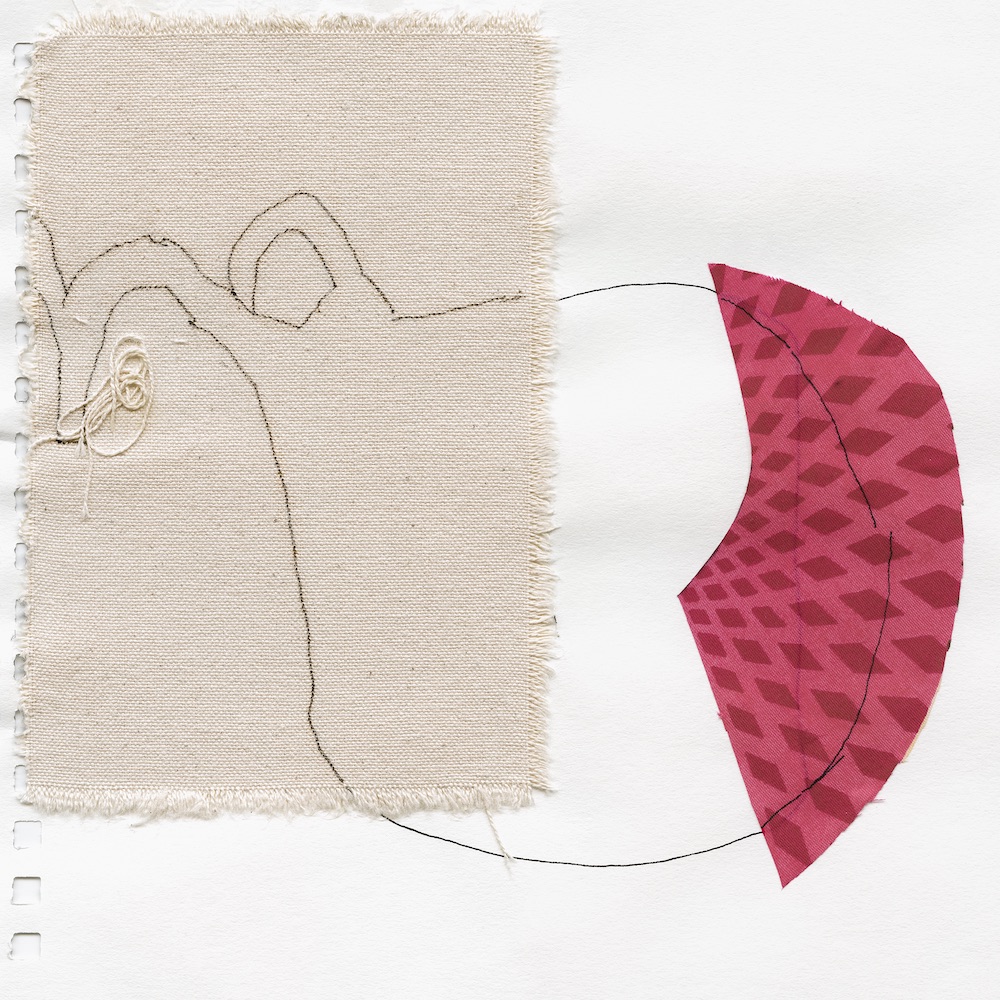

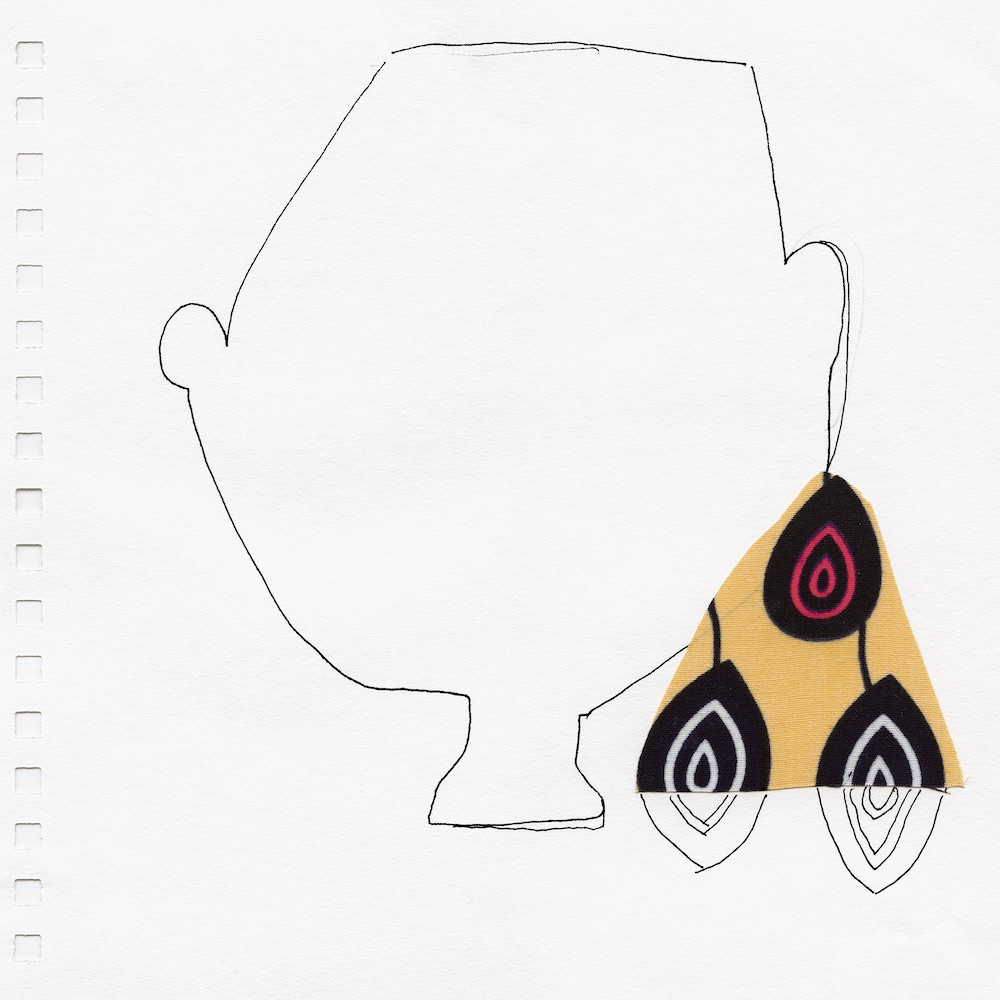

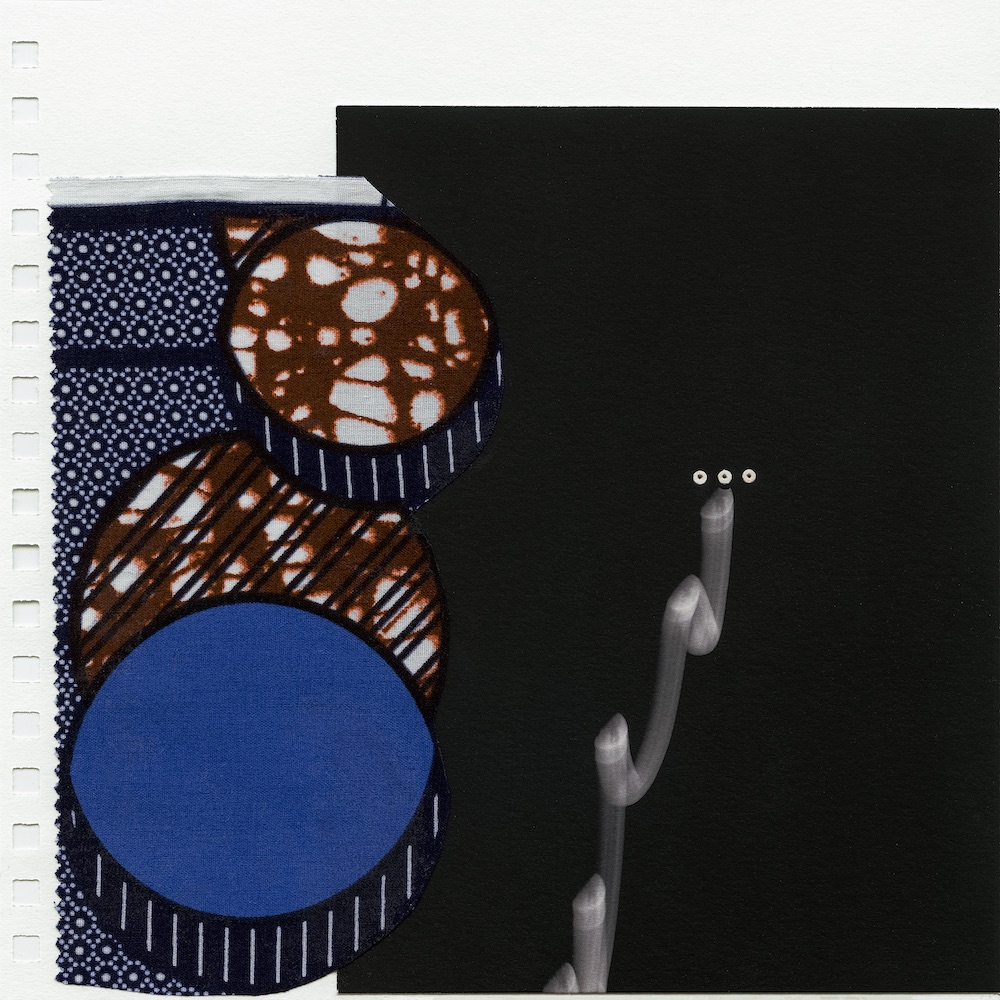

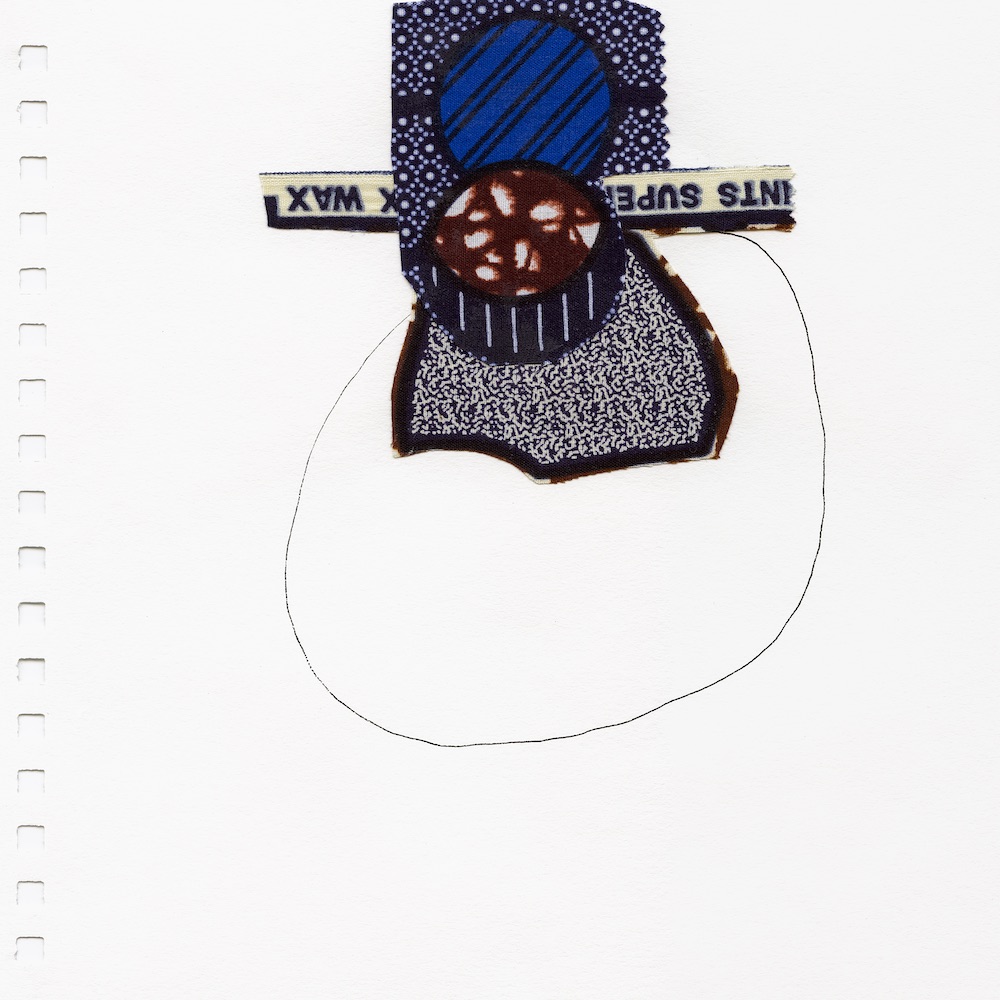

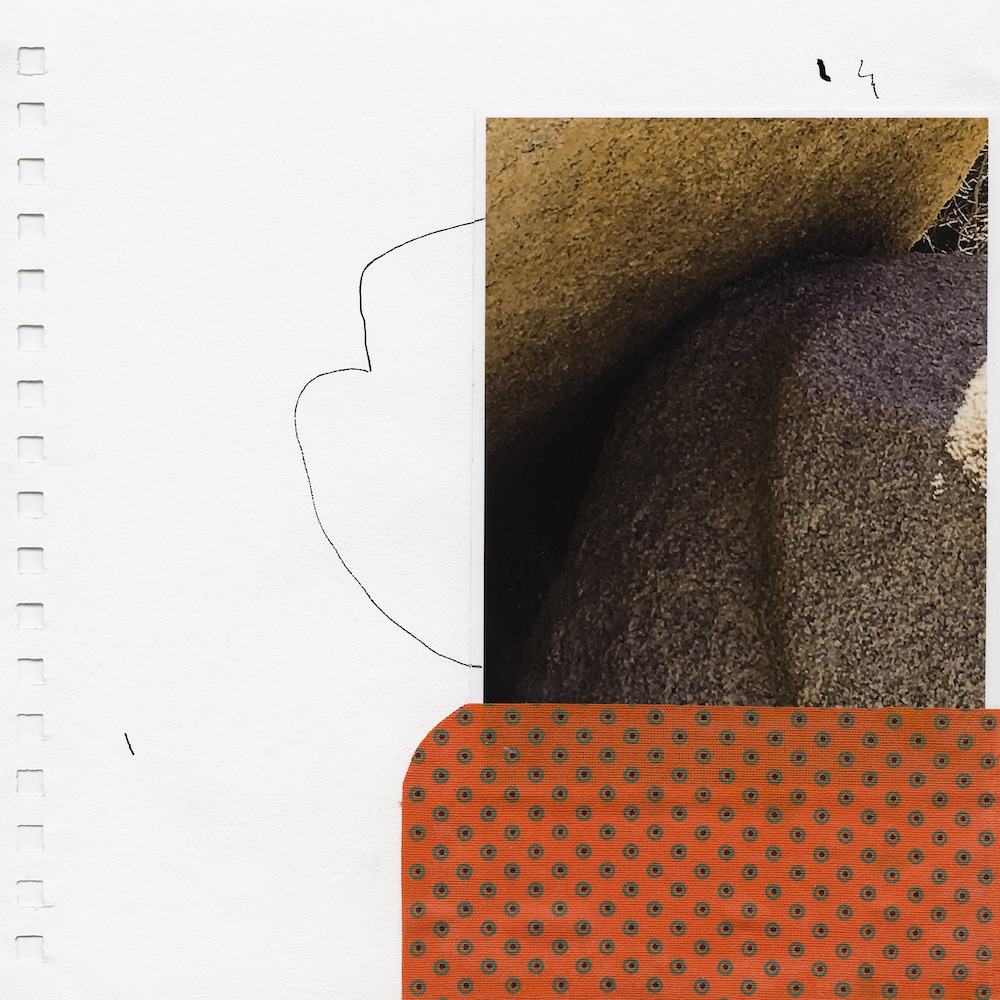

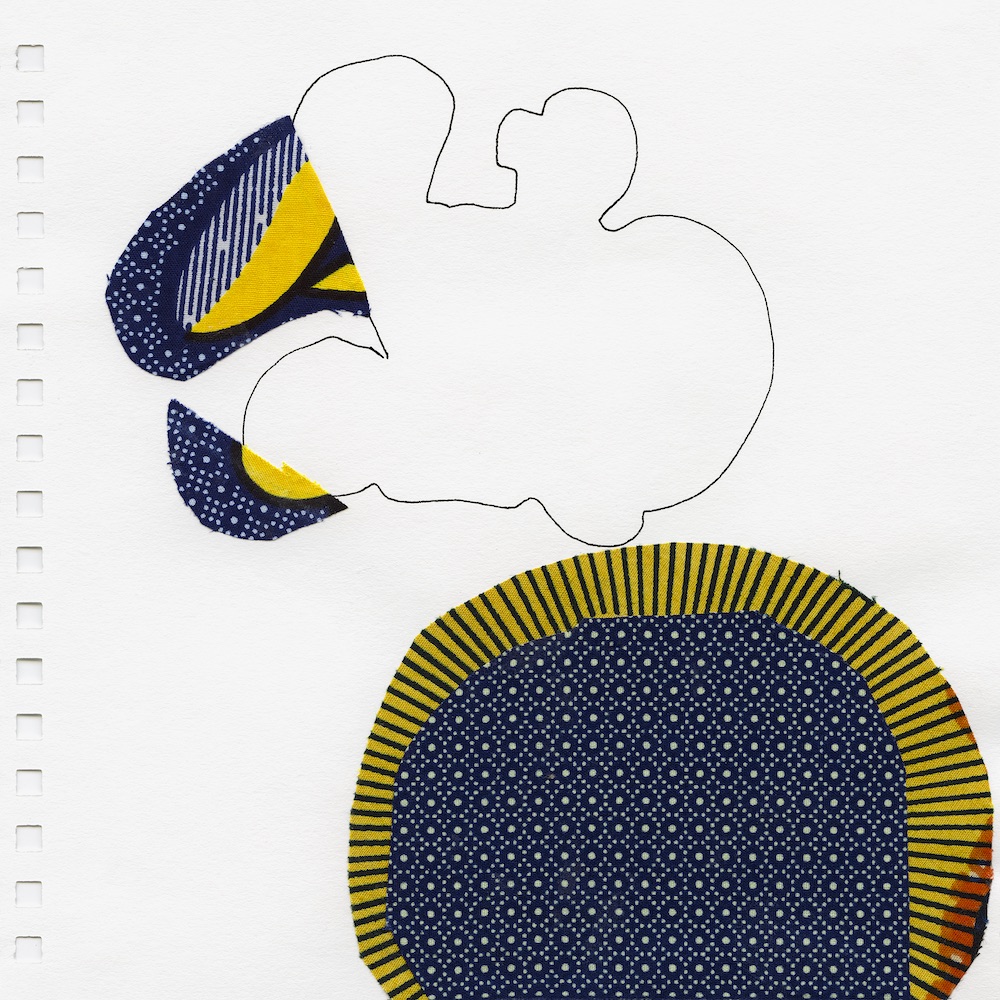

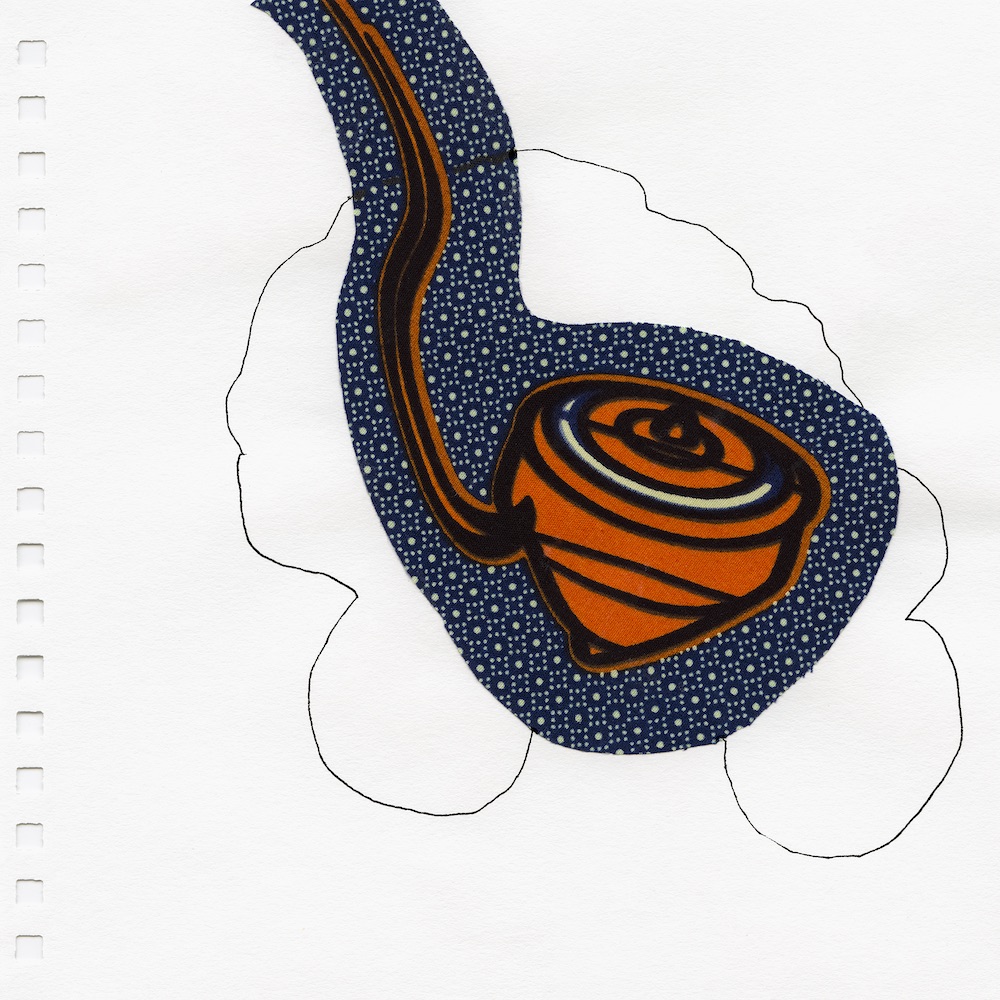

Jo, whose faculty for visual poetry is matched by her perceptive and radiant use of language, had produced an artist’s book. Although it shares its biographically evocative title with the BMA show, the book features collages that have inspired a series of prints now on view in the exhibition Jo Smail: Bees with Sticky Feet at Goya Contemporary Gallery, which published the volume. At a time when many familiar sources of connection and comfort have been cut off, quietly turning Jo’s thoughtfully composed pages has been therapeutic, particularly because the volume addresses the ways in which she has met adversity and flux with unstoppable creativity and an unflinching capacity to love.

Because of the uncertainty of the fate of Jo’s museum exhibition when we were invited to develop an interview for BmoreArt, we decided to focus on this book, which is available through Goya Contemporary and the BMA store. Happily, the BMA has since announced a reopening date of September 30 for its exhibition, which will continue through January 3, 2021. Bees with Sticky Feet is available for viewing by appointment through October 20 at Goya Contemporary.