It took four days after the November 4 election for the presidential race to be called for Joe Biden. At another point in time this might’ve been unthinkable, but in 2020, eight months into a pandemic that has killed more than 235,000 Americans and ushered in the deepest economic depression since the Great Depression of the 1930s, it seems no news story can surprise me anymore. Call it numbness, but trying to locate joy about the Biden victory feels like reaching for the storage space in the cupboard above my fridge—with effort, I can peer into it, and I certainly prefer to have it than not, but it is too small and out of the way to hold anything essential.

Even so, this election was historic for other reasons. Namely, more people participated than ever before: a projected 159.8 million voters to be exact or about a 66.8 percent voter turnout rate among eligible citizens. These numbers are exciting, and progressives have to hope that this is a sign of better times to come, with a more engaged citizenry demanding better and more inclusive policies for all Americans. This pursuit of a better life for “all” citizens has always been the qualified purpose of our democracy, awarded first only to white, property-owning men. Over the course of a few hundred years and in a process that still continues with fits and starts, other groups of Americans have fought for and won these rights.

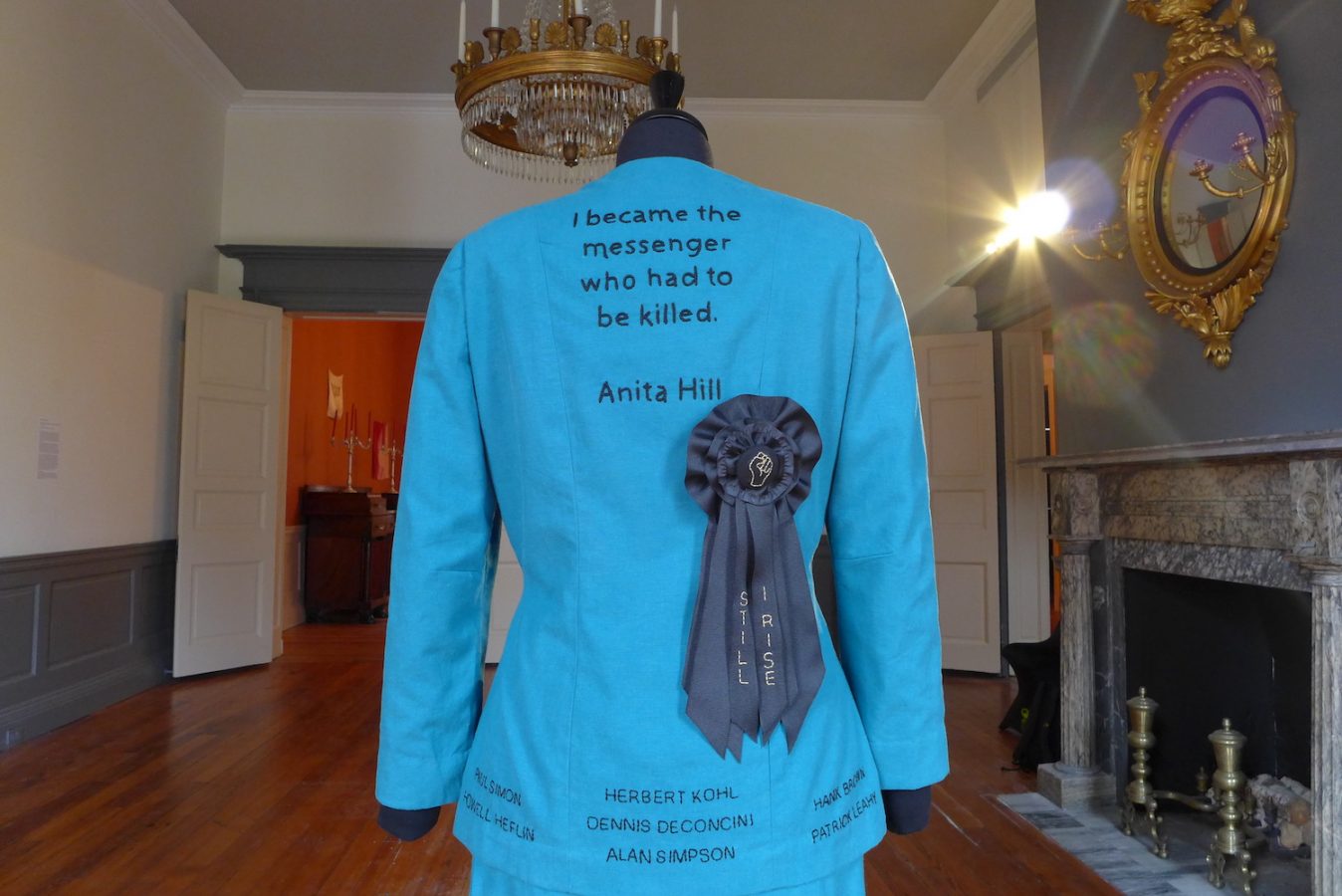

Currently installed at the Peale Museum at Carroll Mansion, the exhibition Rights and Wrongs: Citizenship, Belonging, and the Vote examines the central question of which American citizens have gotten suffrage, when, and how closely their right to vote has been protected. Securing grant funding from The Awesome Foundation and the Maryland State Arts Council, artist and educator Lauren Adams worked with local artists Erin Fostel, Antonio McAfee, and McKinley Wallace III who each worked within archives to create new artworks about the injustices that marginalized people have historically faced in Baltimore.

Fostel used archive sources to create a two-dimensional drawing that viewers can walk around. McAfee has filled a room with his manipulated film-like portraits of African Americans, working at a larger scale than his recent exhibition at the Walters Art Museum. Wallace has created two paintings for the show, which he recently told me about in great detail, that delve into the personal history of Augusta T. Chissell and Margaret Briggs Gregory, two Black Baltimore suffragettes.