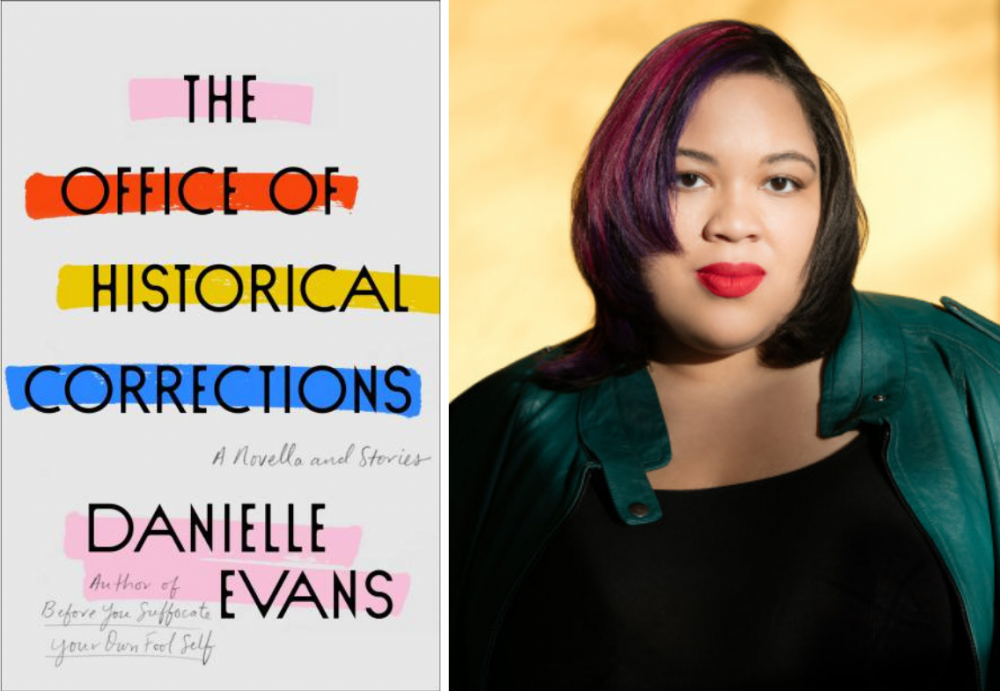

One of the most pertinent lessons throughout many of the short stories is that danger is often familiar… too familiar. Given the multigenerational scope presented throughout the book that arrives with this lesson, could you elaborate further upon any influences, either personally and/or through the Black women literary canon that taught you?

I’ve read a lot about relationships between women and I’ve read a lot about friendships—which is interesting to me because friendships are one of those places where you have to choose it over and over again. It creates an interesting structure for fiction because there is this classic version of a story where there is a marriage plot that has an inherent kind of closure. Either people get married or they don’t. Once you are in a relationship that is defined that way, it takes some doing to get out of it. But friendship doesn’t really require a plot to undo or do. Friendship requires choice.

I’m interested in the ways that you create inherent arriving action or mirrors for different versions of yourself when you compare the point in which you choose your friendship with somebody to the point in which as a different person you are still choosing that friendship, or the point at which you no longer choose that friendship because it is a more dynamic relationship. One of the writers that really captures Black women’s friendships and Black women’s long-term friendships is, of course, Toni Morrison. Sula is the obvious book that explores that most directly, but I also think about the friendship between Violet and Dorcas in Jazz, which is wary and difficult. There is a way in which they see each other that pulls them together in a world where other people don’t see them as clearly.

One of the things that you want to have the freedom to do as a Black woman writer is to write characters who are not warm, and open, and not trying to fix everybody’s life in the way that a lot of the more cliche Black female characters who appear in popular culture are.

I think that how long women, Black women in particular, have been writing about that is both reassuring and it feels like you have predecessors.

One of the fantastic subtle nuances of the book is how you weave complex geographical stories to guide narration. How do you draw the line between placemaking in lieu of crafting fictional stories, but also capturing the essence and experiences of very real locations?

That is a question that I answer differently story-to-story because some stories are set in very real places, some stories are set in fictional places, and some of them are set in hybrid spaces. The answer is different depending on the terms of the story. The question is how I then clear enough in the story where I signal something about the world in which it is happening. I’m interested in spaces because I think that all spaces have an interesting echo of time. Location is an interesting echo for time because space is always what you are seeing right in front of you, but also it has some kind of history, and it has its own history independent of what you remember.

And place usually has some suggestion of what is happening. Are [the spaces] decaying? Are they being rebuilt? Are they shifting in some way? I think I am most interested in space as an echo for how time works, space as a way of thinking about memory, space as a way of thinking about the difference between the version of a character who saw the place for the first time and the character who is seeing it now. And that is how I hugely think about details and how to capture space. Place is very much tied to the character.

So much detail about the physical landscape for me comes from both the sense of time but also a very specific embodied experience of the world. Where is this character comfortable? Where are they on edge? Where are they on guard? And where does this come from?

When creating characters like “The artist” in the story “Why Won’t Women Just Say What They Want,” is the intention for them to be ghoul-like haunting figures? Because that character is still personally haunting me!

I think that was the only story that I’d specifically written that was in response to a topical event. I started the story with the thought of “Oh, this is going to be silly,” but then when I started writing the story, it was less fun than I thought it was going to be. Because I think there is something really absurd about the artist, but there is also something really harmful. That is often a part of the ingenuity of people who are harmful.

Once I’d realized that there’s an engagement with trauma in this story, I wanted to put pressure on the absurdity. The story both escalates in its absurdity but also in its level of emotional intensity, and also shifts in that it starts focusing on this character but then gradually you begin to see around him. It becomes both a very cliche and familiar version of the public apology that I’m poking fun at, but also more of this complicated story of all of the people who exist around the periphery of that apology. And I think that it was important to me to capture not just a terrible man and salient people but the ways in which other people adapt to a world in which people get away with harming them.