If an artist makes new work during a pandemic, is it automatically considered “pandemic art”? While many artists create in response to current events, which can imbue the work with relevance, others create to deliberately escape from reality. However, during the pandemic, even art made to promote an escape to a better, safer, or more healthy space was created within the context of COVID-19. Whether or not an artist chooses to directly address current conditions, politics, and social movements, either way, in the past year they were making art in response to the largest medical and economic crisis of our time. What’s interesting is that, in both scenarios, artists are envisioning solutions to the problems that plague all of us. In bringing their vision into focus as physical objects, they present new paths we can take as a society.

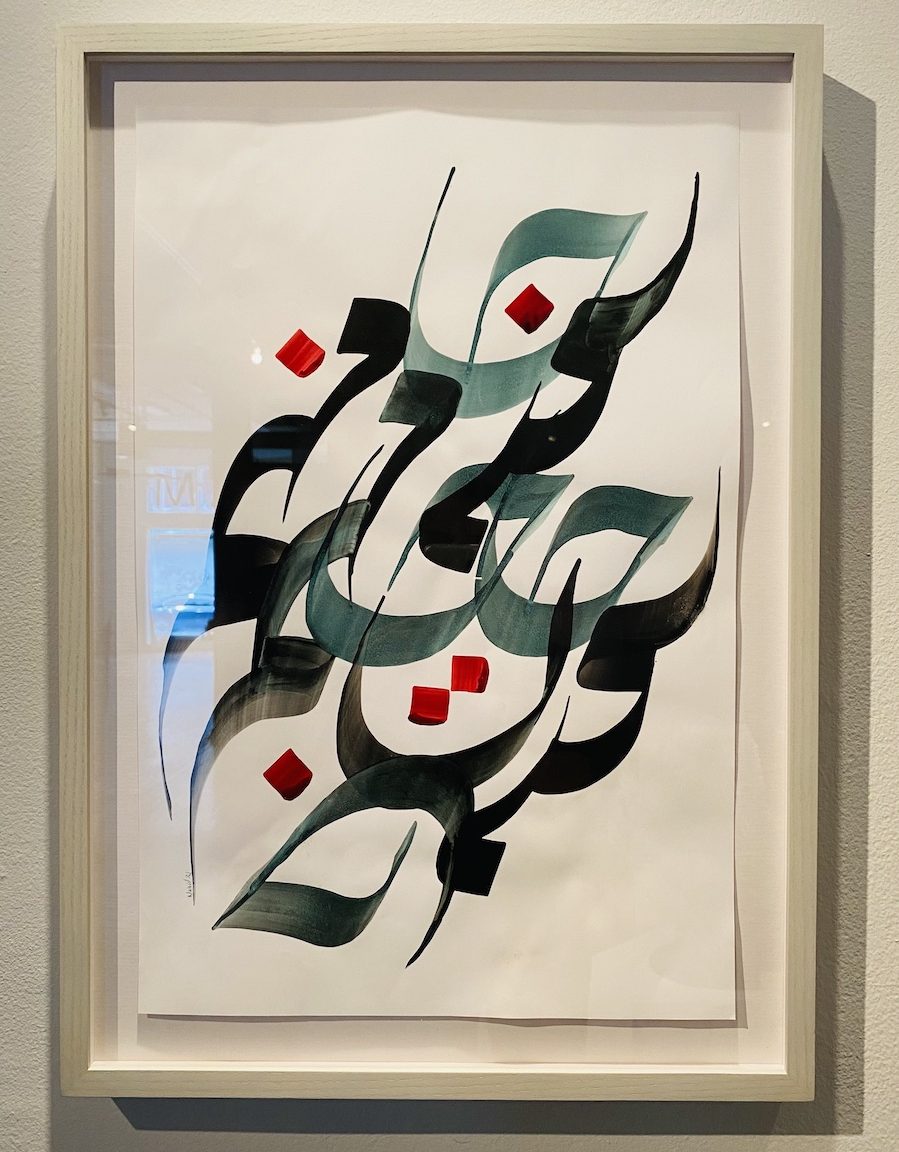

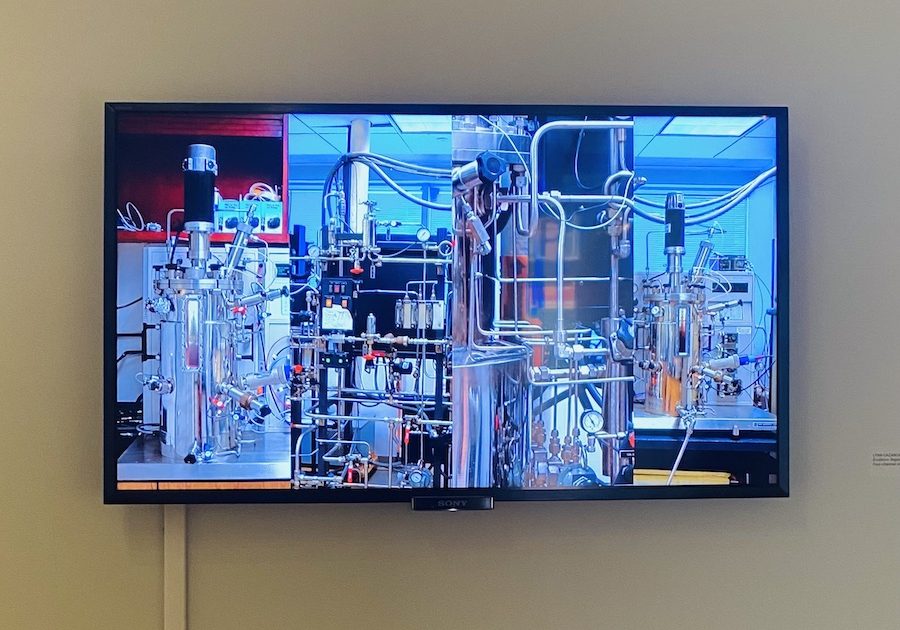

Spark IV, an exhibit produced for the past three years during the festival Light City as a collaboration between Towson University and the University of Maryland Baltimore County (UMBC), presents a convincing case for a collective and multifaceted vision for the future. Hosted this year at Maryland Art Place and curated by Catherine Borg, the exhibit considers a number of interrelated and overlapping themes—“altered time, imagined places, future focus, climate horizon, and equitable future”—with many of the works addressing several concepts at once, within different layers and contexts.

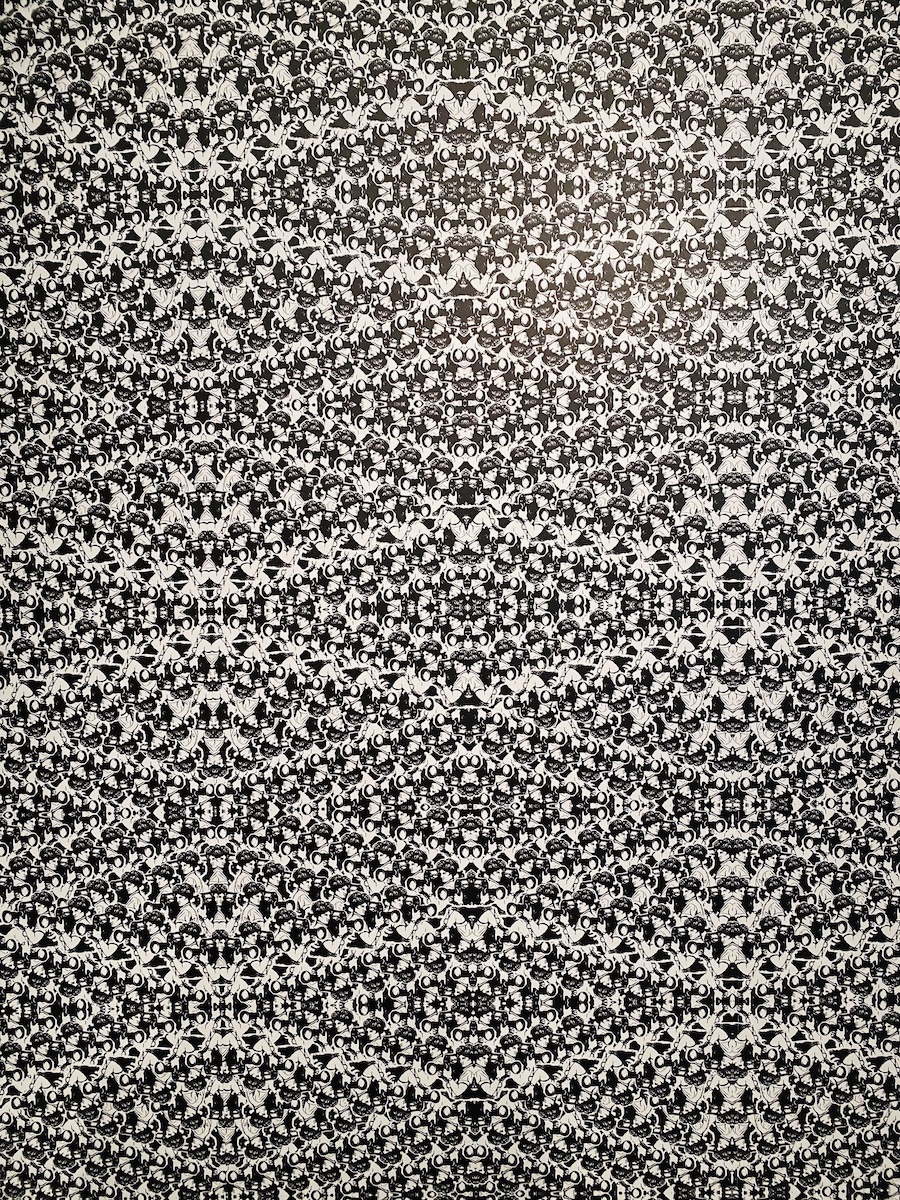

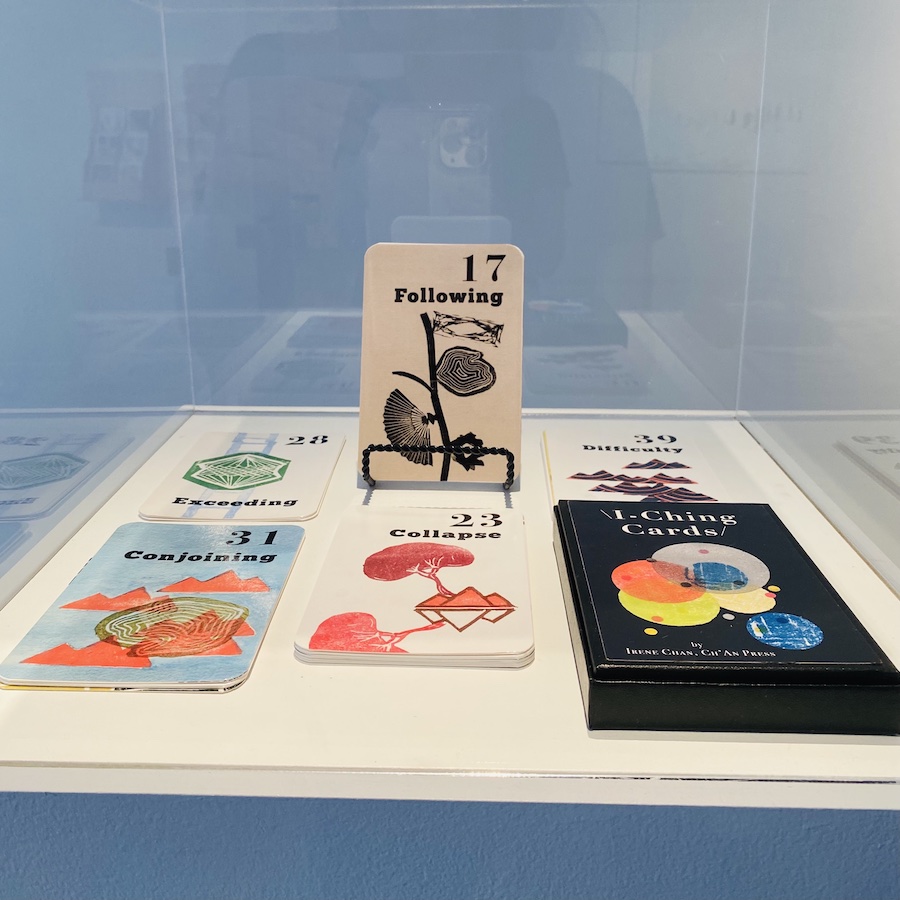

This large multimedia group exhibition, up through June 26, considers the impact of the dramatic mass shutdown in March 2020 upon minds, bodies, and society as a whole. While isolated at home and focused on individual glowing screens for connection, we watched as painful truths were laid bare about inequality, public health and safety, and police brutality and racism, especially after more extrajudicial police killings of Black Americans in 2020 and the subsequent protests that arose across the world. The premise of the exhibition Spark IV posits that once most aspects of normal life were taken away, artists were free to imagine new narratives for our individual and collective lives, both for the present and the future. The artists in this exhibit look to the past for insight and attempt to provide models for collective action, adaptation, healing, and the possibility of building something better going forward.