Can I ask what AI software you use?

I use NightCafe Studio to generate images, and also the apps FaceswapLite, Snapchat, Instagram, and a kids’ greenscreen app that’s just called Green Screen.

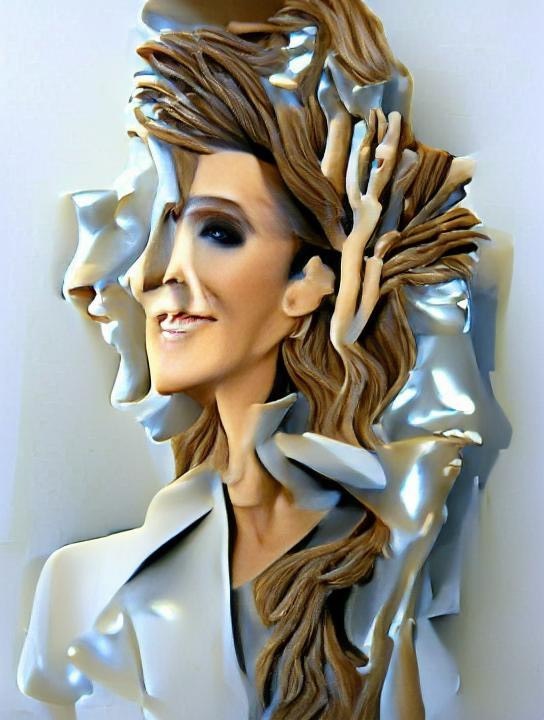

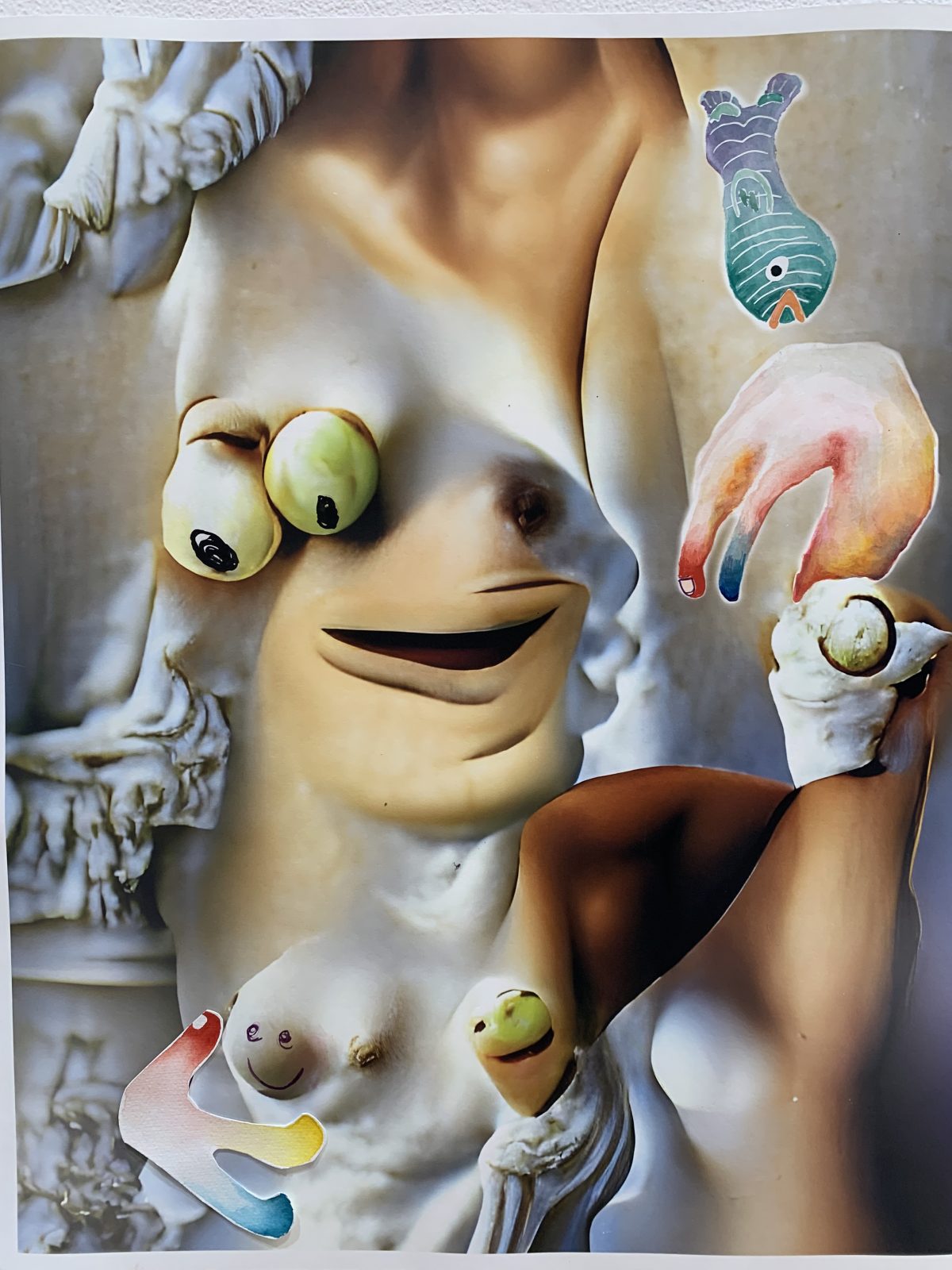

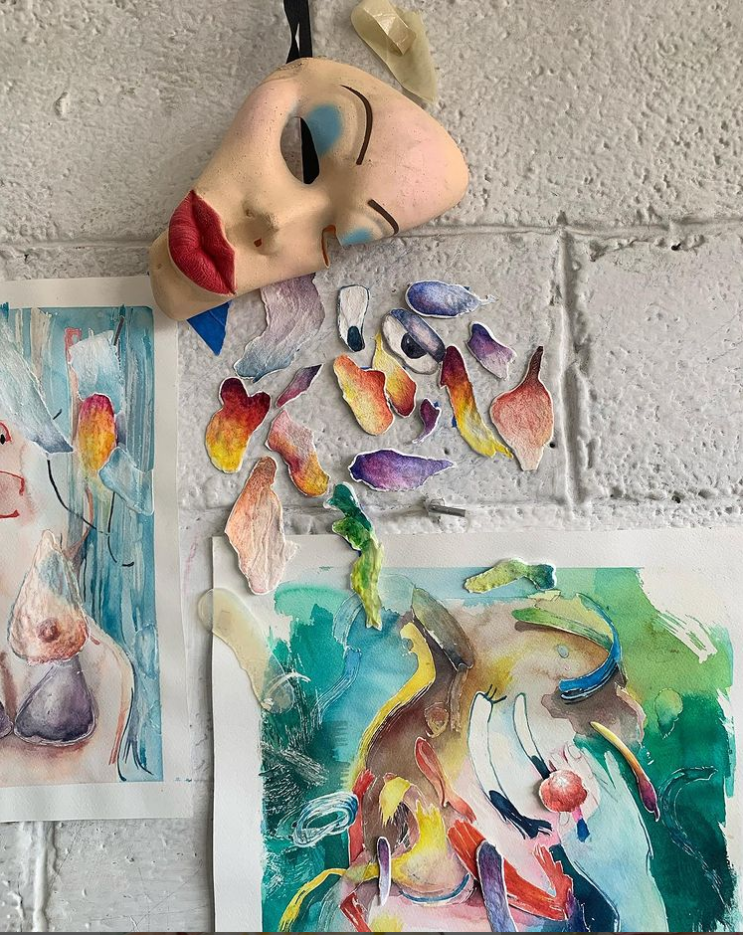

It also goes back to, how do I bring my body into this again? In this recent exhibition, it’s through collage and hand cutting and actually putting pieces together using my body a lot, whether in video or making hand-drawings of machine-generated images, it’s just feeling constantly in conversation between the body and the machine. And then I also sometimes feel like I should have something intelligent to say about being cyborgs or how connected we are, but I still haven’t totally wrapped my head around it. Maybe I’m still figuring it out. There’s a lot of this conversation, these kinds of questions, to blur the boundaries between our physical selves and digital selves. Is this something that is an empowering new way to be? Or is it just a given? Is this just how we are? Are we more than our bodies?

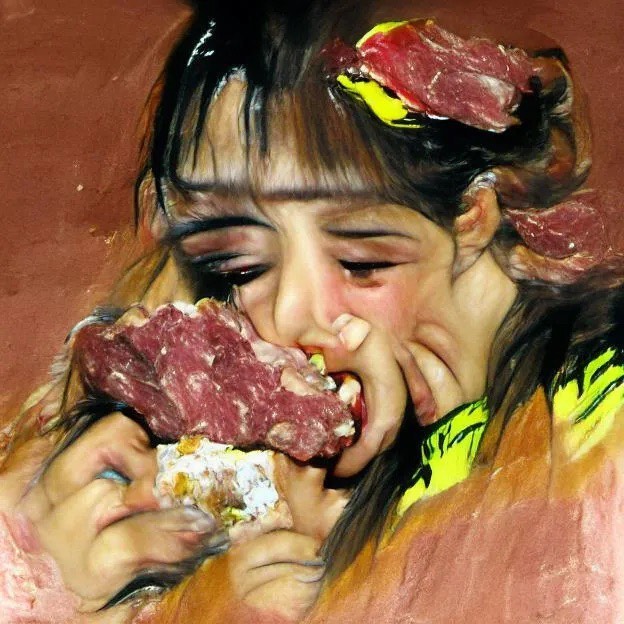

It’s funny, I was thinking about how the AIs not only generate uncanny human anatomies but also really strange anatomies of landscapes or architecture! Maybe that’s something I notice more because you use watercolors so much in your work, and it’s a medium (for better or for worse) that we’ve always associated with landscapes. As a viewer, I feel like my subconscious is always trying to understand the physical space in your work, which leads to an interesting tension. The anatomy of these non-specified references to the figure float and bleed into, or sometimes stand out, from these vague illusions of physical space. Both painters and AIs are programmed to make believable illusions of space, and it’s so disorienting and fun when they “fail.”

This has been one of the more interesting discoveries in my foray into working with an AI. Looking at my process in the watercolor work, there are some similarities in how the computer develops an image and how I develop an image. In the watercolors, I often have a sketch of a loose idea—this is going to be, like, a fire or something. I sketch it out loosely, then I use a lot of masking fluid (kind of like a liquid Iatex) on the paper. Then I do a big wash of color and it leaves a lot of white areas [where the masking fluid was]. And then most of the work in the watercolor is filling in the white areas, and there’s a lot of randomness that happens in that first stage, which I do fairly loosely. The challenge is to fill the rest, and it ends up not being anything like the original sketch because the composition has changed. It’s filling in these areas and making those become parts, so a stroke of the white becomes almost a character itself.

While watching these AI images emerge, it starts with a few dots, and then they build. Each of those dot points in the image starts building up to whatever the text prompt was. And the composition doesn’t totally make sense. It’s hard to articulate this, but I kind of am filling in and adjusting to the composition. Even though it’s not totally random when I’m putting it on the paper, there is a sense of randomness—maybe just in the way that the watercolors have spread onto the paper, or an initial stroke because I wasn’t totally paying attention to it. I can’t say I’m working with the same logic as a computer, but there is something interesting, watching [an AI-generated] image develop at 25 percent, 50 percent, 65 percent.

One of the things that I’m also fascinated by is not only how the computer interprets the prompts and the text, but also how we interpret the images that the computer creates, because they’re never the things themselves! You’ll look at it and it looks like there’s some figure in a garden, for example, but there’s not a clear definition of what the figure is or what the flowers in the garden are. But it’s how our eyes have learned to interpret the symbols or even textures they evoke. And I think that makes these images successful.

This is what painters have been trying to do forever. We’re constantly trying to find new ways of presenting these symbols for the eye to interpret, but also let them become their own thing. But then this AI comes along, and look! It can just do it in a few seconds! In a way I’m jealous of the machine, even though I’m working with it.

Part of what’s so uncanny and weird about computer-generated images is their impulse to fill every surface with vague detail, because that’s what “reality” looks like, but that’s not how human eyes perceive the world. We generally don’t notice much of the texture of negative space, but CGI has an horror vacui because so much was developed for rendering or editing techniques like the “content-aware fill” tool. And your paintings are kind of like that. That may be why they exist so comfortably online as photos next to “photos” of digital images. The frame of the Instagram grid or story format becomes the negative space, and our brains are more accepting of their weirdness because we’re used to looking at digital photos and accepting them as “real.” We are more open to accepting the “veracity” of photographs or point-and-shoot video, and when you hack those processes with these hyper-saturated, fabricated images, they become so truly trippy.

I like to think of my work as a nice “break” from Instagram content. The other day, a painter friend was asking me if she should post “thirst trap” selfies on Instagram alongside her work, and I realized maybe my work is about trying to make the opposite of a thirst trap. What would the opposite of a thirst trap even be? Maximalist grotesque? I’m just seeing far too much of this cleaned-up perfection on there! When we talk about Instagram specifically as a platform—as a tool—there are certain connotations or associations with it, like, “oh, yeah! the influencers with the perfect life! It’s very aesthetic!” Whereas I’m looking at—all disturbing Zuckerberg stuff aside—well, this is a fantastic tool. Look at all the things that we can do!