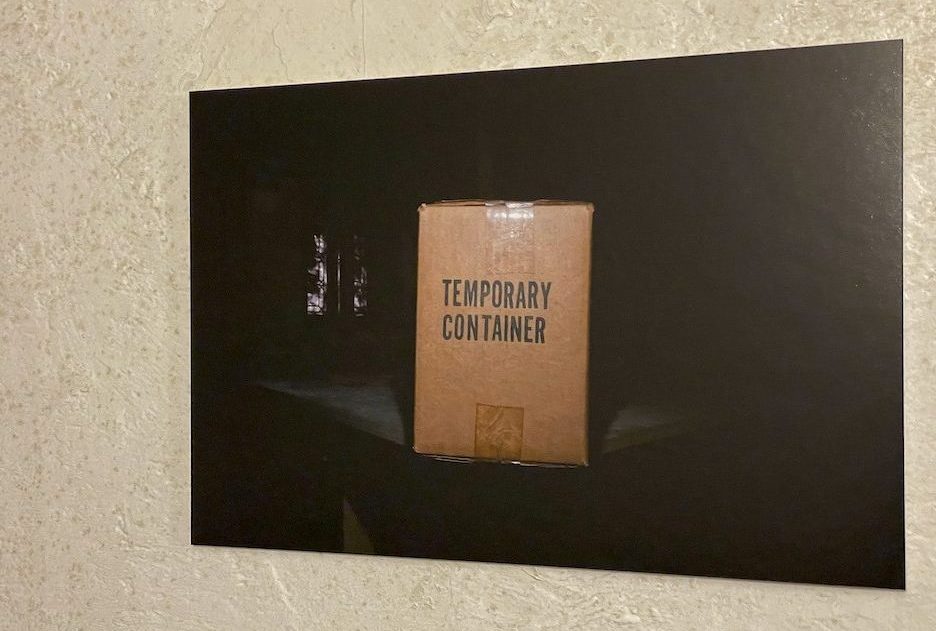

Around the corner, there’s an opening to an even creepier chamber, in which the cremains had been discovered. Here, a glowing, stained-glass-like installation by Stephen Hendee recreated various vessels of unclaimed remains—of which apparently there were 15,000 cases nationally in 2018 alone—in brightly-colored, LED-lit translucent polypropylene. The boxes become an eerie beacon, resisting the risk of being forgotten and ignored.

On the second floor, dreamy photographs by Jill Fannon (frequent BmoreArt contributor) from the series Care in the Garden pay tribute to healthcare workers who served during the COVID-19 pandemic. They’re installed in a cabinet in a small antechamber, implying a quiet intimacy. “Aurora (PA in her Garden at Home)” depicts the titular masked physician’s assistant basking in sunlight, engulfed in a flowering bush. Her eyes are closed as she tilts her head back towards the light—as if recharging in a moment of respite between emotionally draining shifts of resisting and witnessing countless deaths.

In a nearby room, an excerpt from Dina Fiasconaro’s in-progress experimental film There is No One What Will Take Care of You also speaks to themes of caregiving and exhaustion. A video of a young woman slumped backwards, collapsed next to a bed, slowly traverses the wall and floor of the nearly-domestic space. It’s spectral and hypnotic, and apparently from a larger narrative project about a father-daughter relationship tested by addiction.

The drug epidemic also haunts Amy Berbert Vu’s gorgeous, tragic project Remembering the Stains on the Sidewalk, in which the photographer has documented all the sites of Baltimore’s hundreds of 2016 homicides exactly one year after they were committed. The installation comprises framed photos as well as several gorgeously-bound tomes on a table. The sheer quantity of murders is crushing, so it’s impressive that each individual photo is so richly considered and beautifully-shot. It’s an archive of a city in a perpetual state of mourning, and I imagine a future anthropologist pouring over details in her haunting cityscapes for clues as to what went wrong with our society.

The cycle of systemic violence and mourning are rendered with a less clinical eye in the work of Besan Khamis, whose “Into the Flowers (Funeral) 1 & 2” represent the only paintings in the show. Inspired by the Palestinian funerary rites of the artist’s youth, they depict a processions of coffins in deceptively cheery colors. The unusual perspectival space and gravity-defying splatters of colors—are these flowers cascading? ascending?—make these some of my personal favorites in the show. The duality of the funeral as a time of grief and celebration of life is most evident here, as is the sense of ambiguity and mystery surrounding death and transition.

Memento Mori: Amy Berbert Vu, Antonio McAfee, Bao Nguyen, Carrie Fucile and Brenton Lim, Dina Fiasconaro, Edgar Reyes, Jill Fannon, Lynn Silverman, Michele Blu, Stephen Hendee, and Webster Phillips / I Henry Photo Project

The Parlor, 108 West North Avenue

Curated by Catherine Borg

Hours: Fridays and Saturdays, 5:00 – 8:00PM

Closing Reception: Saturday, Dec. 17, 5:00 – 8:00PM

***