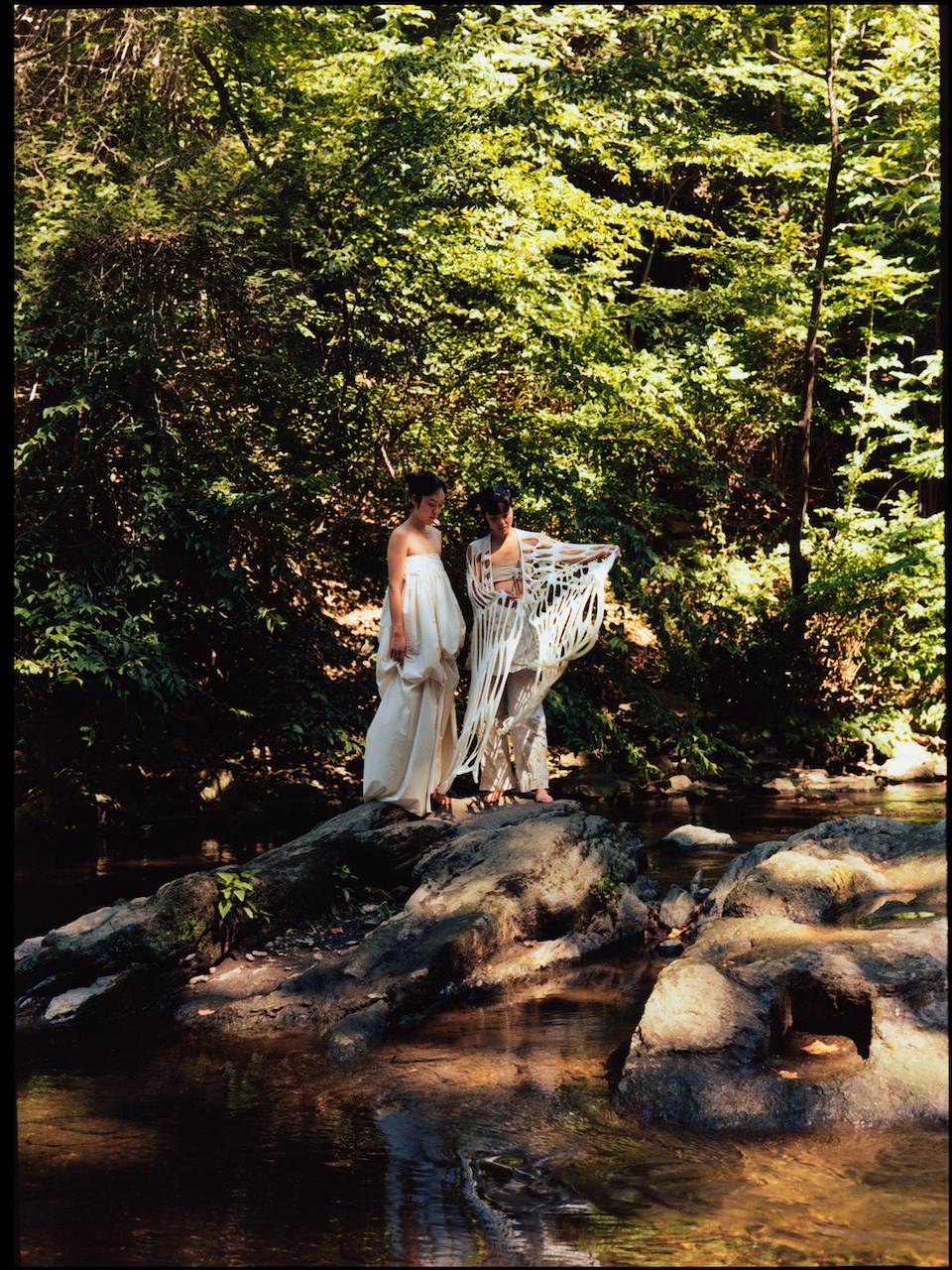

A four-character idiom meaning natural, immaculate beauty, Chun-yee-mu-bong literally translates as “No seam is found in seonnyeo’s clothing.” Seonnyeo is a Korean word for a celestial woman (or a group of them) that appears across East Asian myths as a symbol of beauty and virtue. In Korean folktales, this fairylike character descends to the human world to bathe in mountain springs. The visit of seonnyeo is the theme of the latest collection 날개 nalgae (“wing” in Korean) by Bokeum Jeon, a multidisciplinary artist, MICA graduate, and designer now based in Philadelphia.

Portraying seonnyeo’s visit, 날개 nalgae features a linen top and short skirt with strings, flowy drawstring pants, and a long skirt with high waistbands around the chest—a simple composition inspired by hanbok (traditional Korean clothing). A long, web-like gown reinterprets the winged clothes of seonnyeo, draping from shoulder to toe and adding a light, airy look. The models’ braided buns resemble the typical high, looping pigtails of seonnyeo. The overall use of white fabric echoes not only historical depictions of Koreans as the people of white clothing, but also the aforementioned expression, which alludes to seonnyeo’s artistry and craftsmanship as a maker of their own clothes. Jeon presented 날개 nalgae at the fourth-annual fashion show Fantasy Machine at Current Space in October 2022.