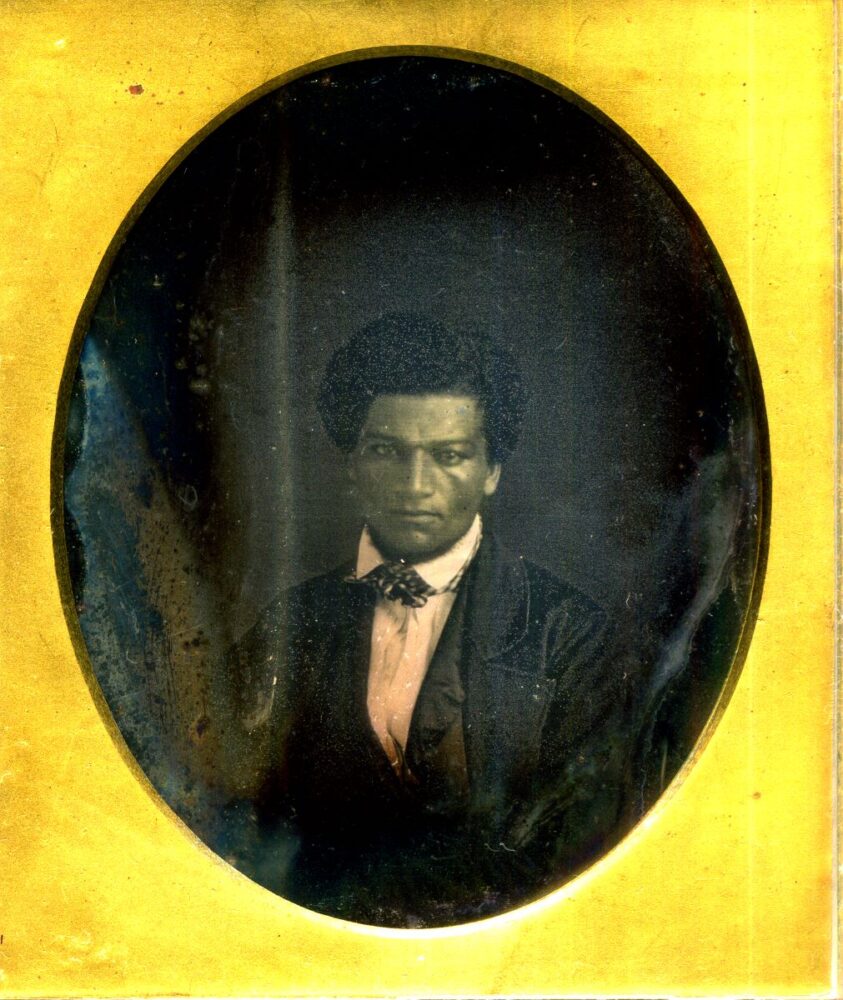

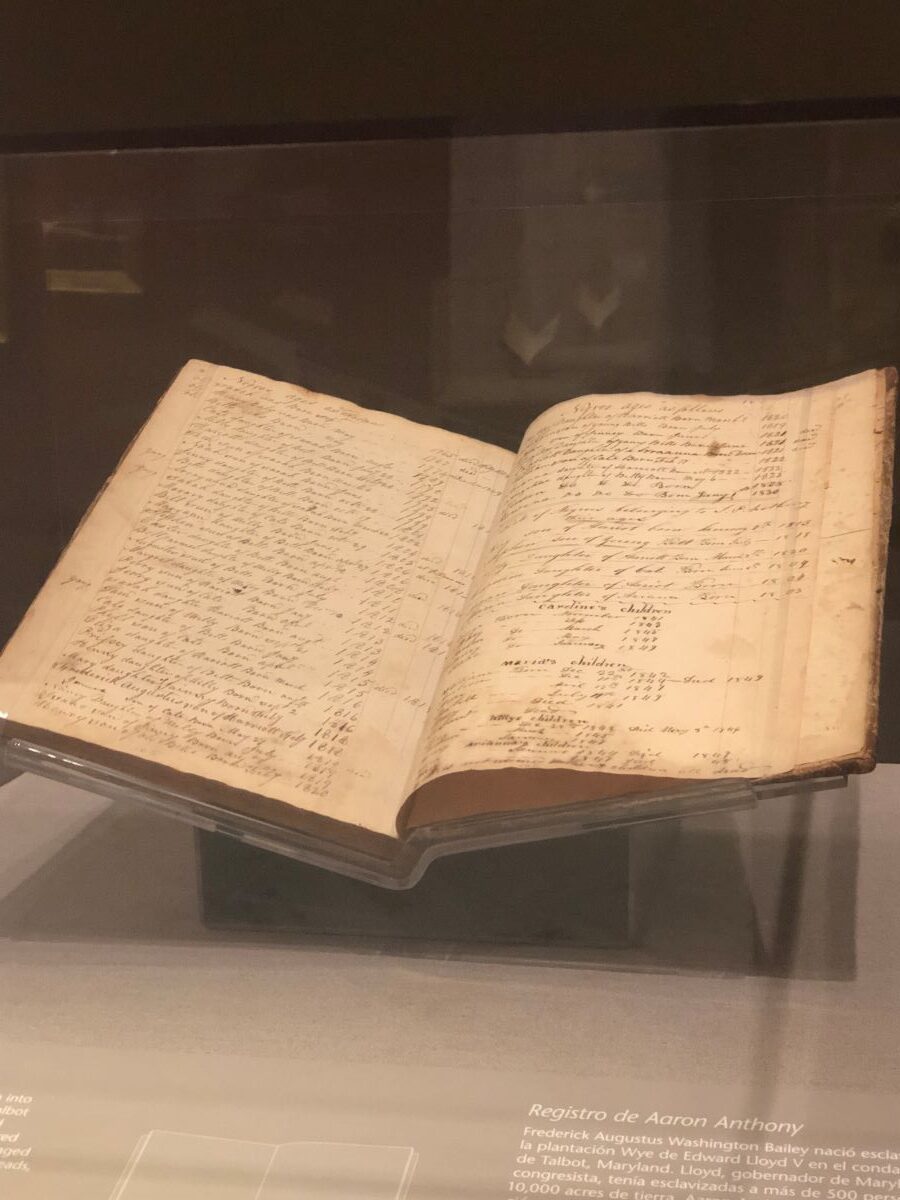

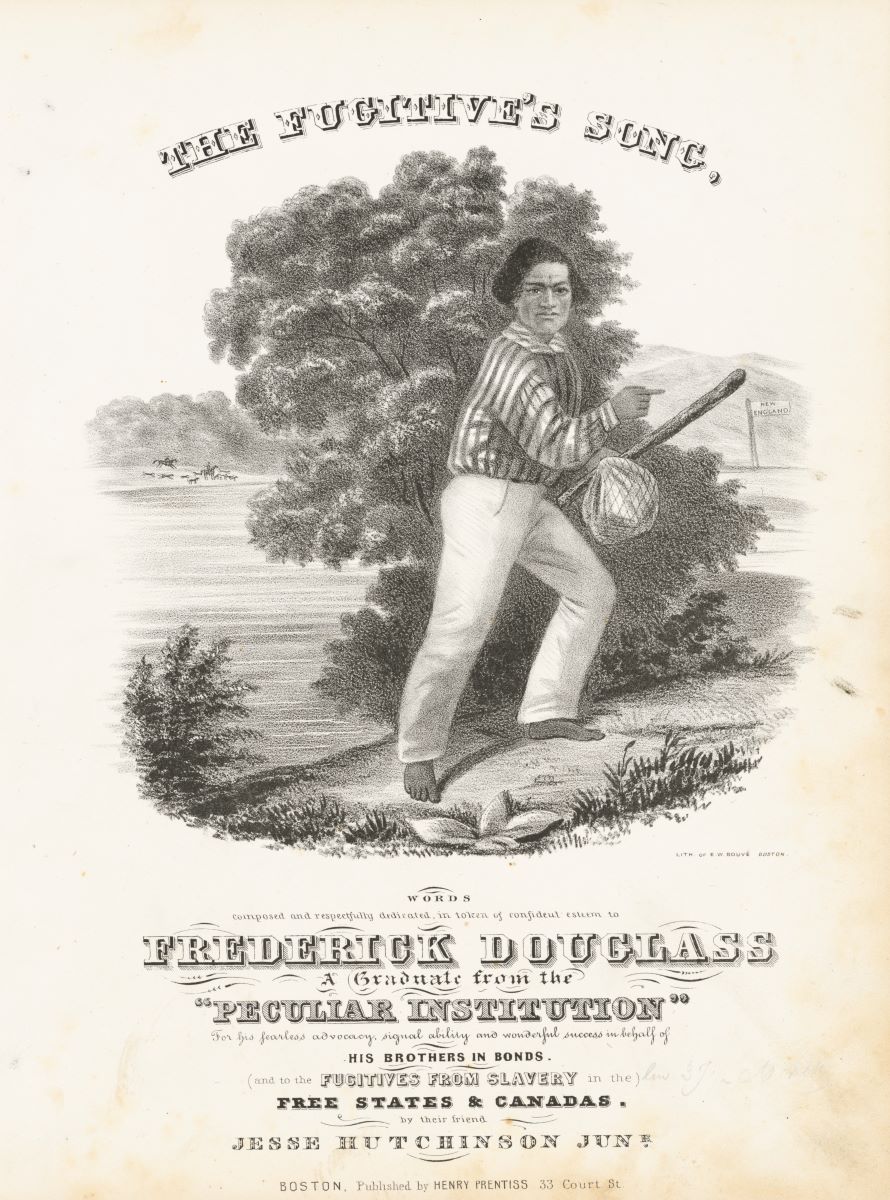

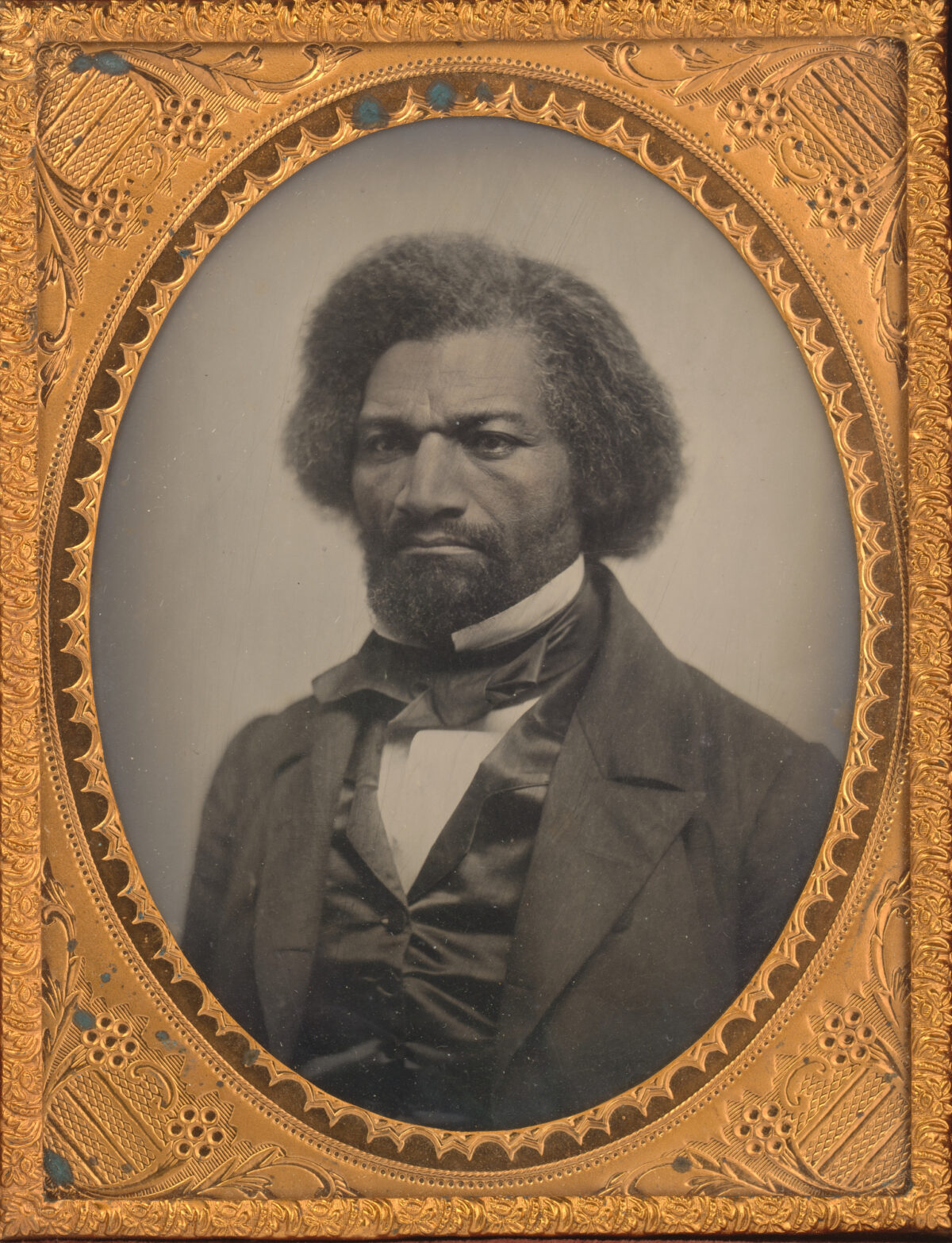

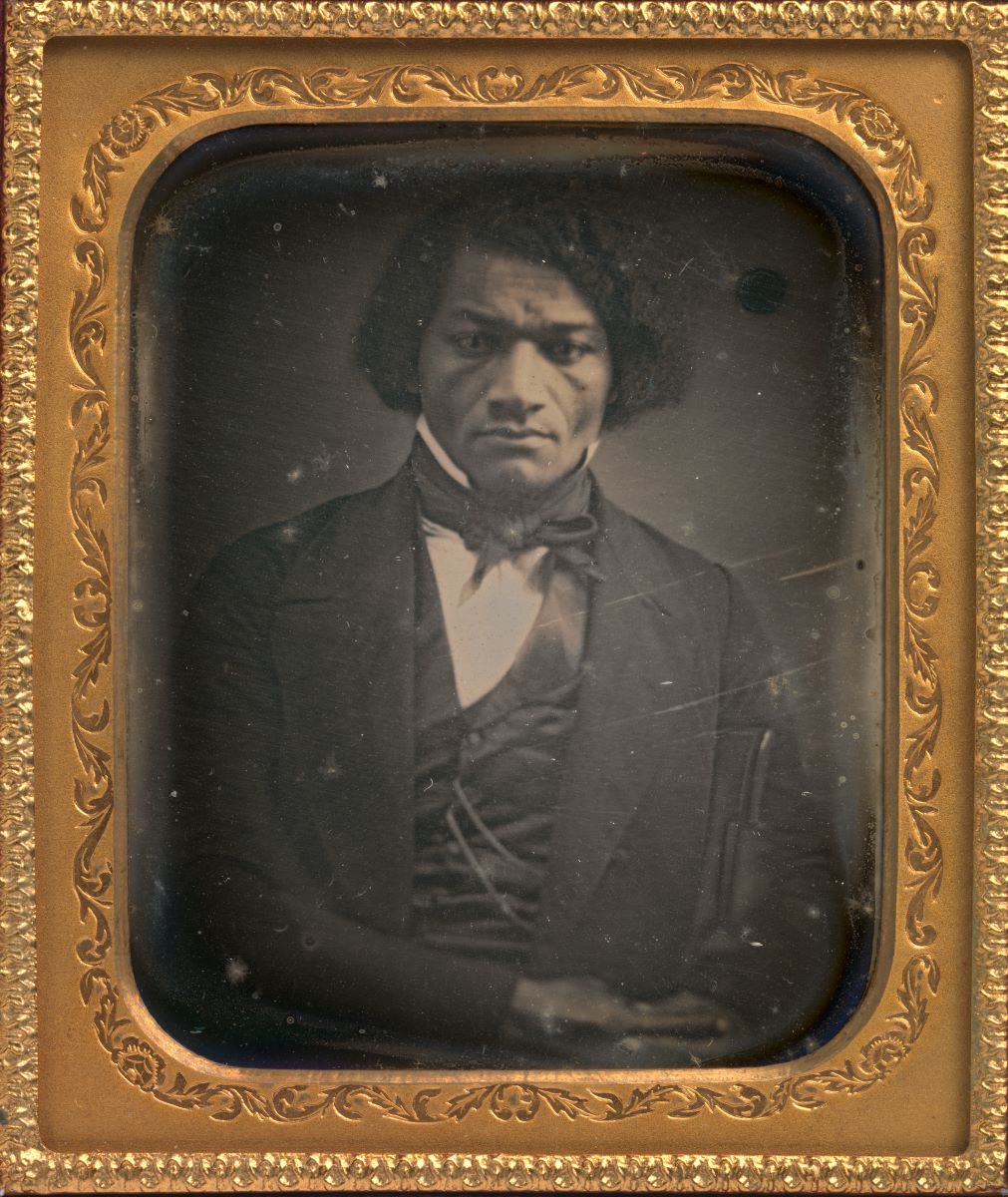

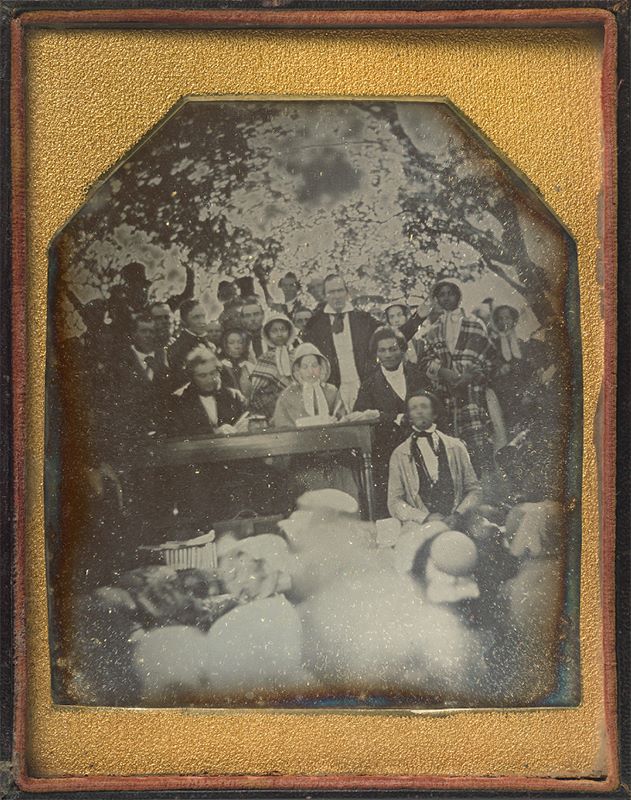

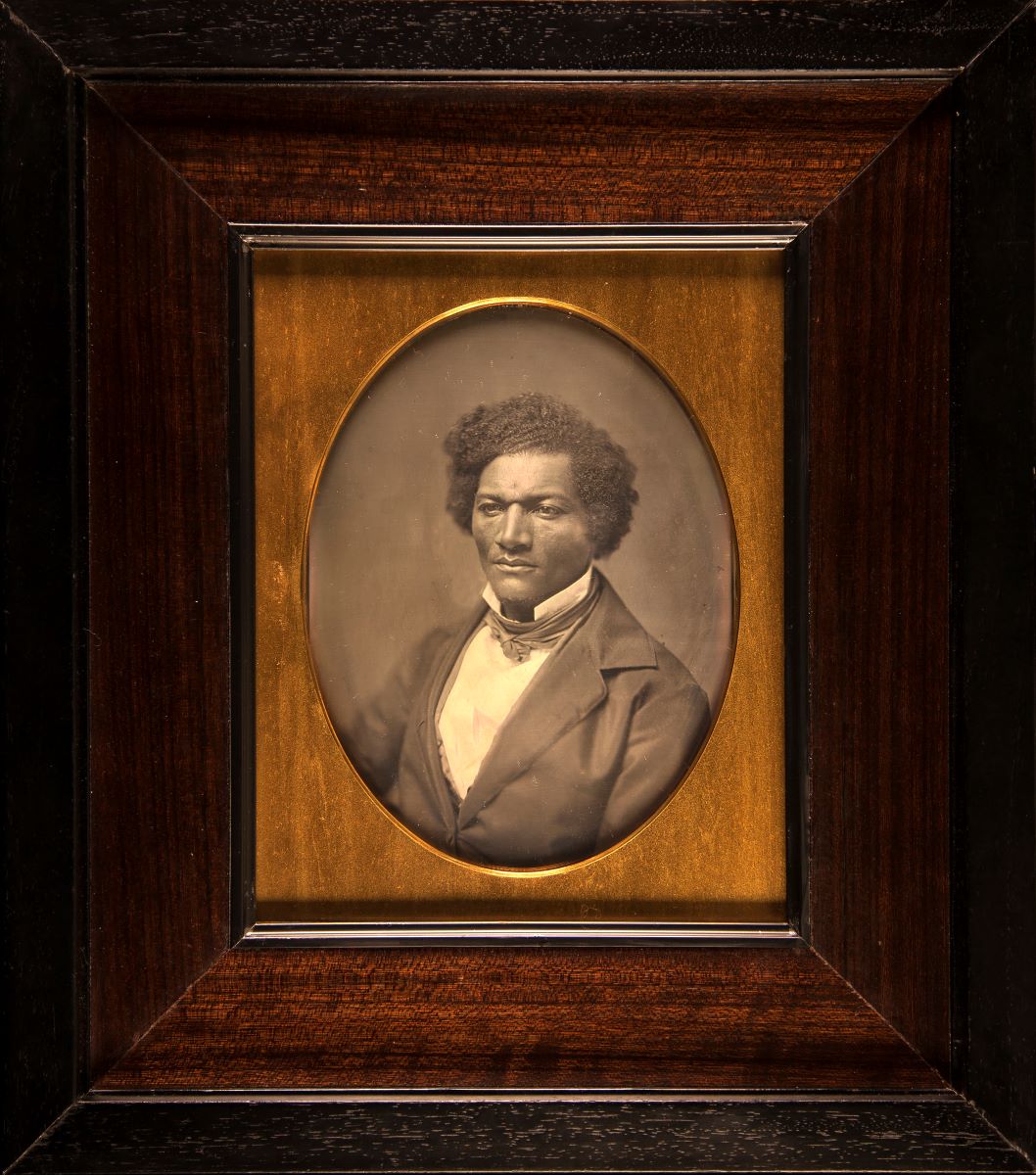

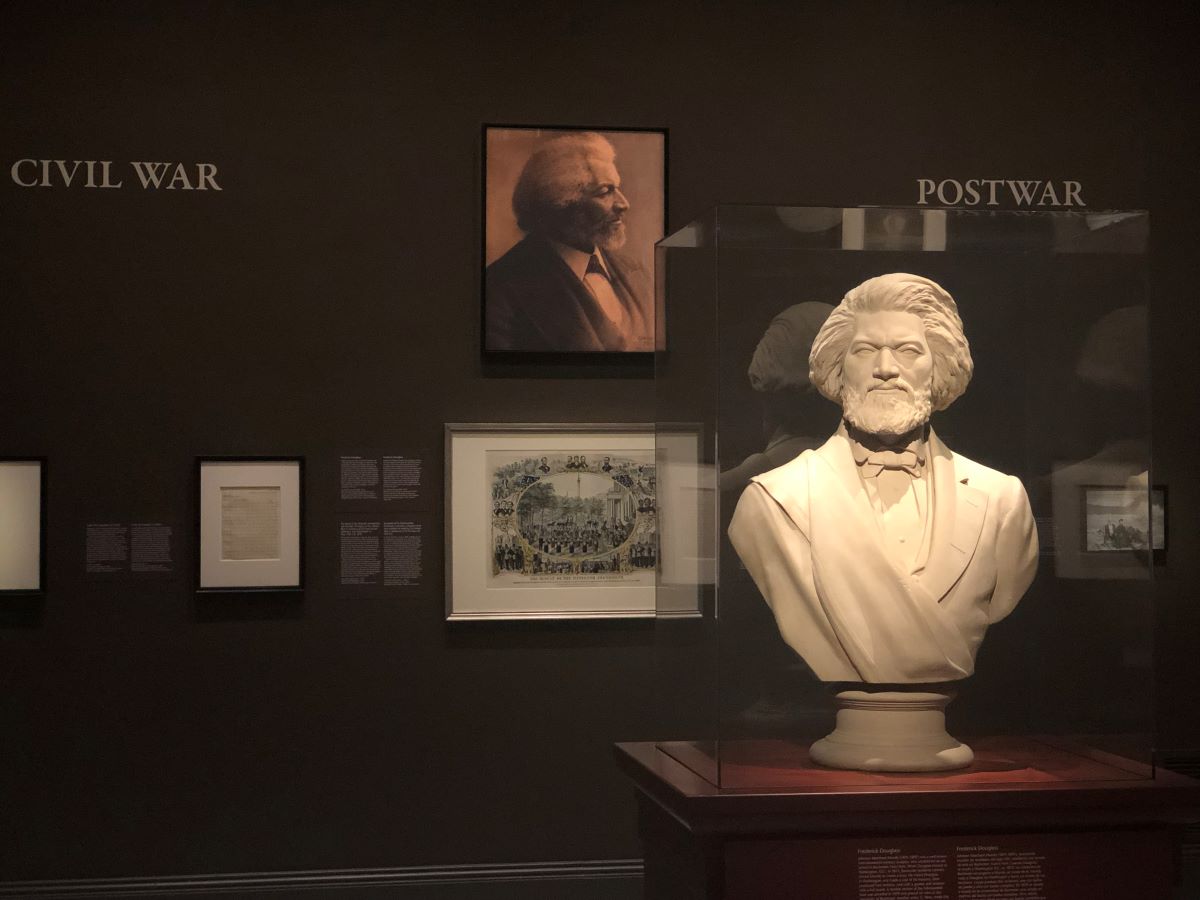

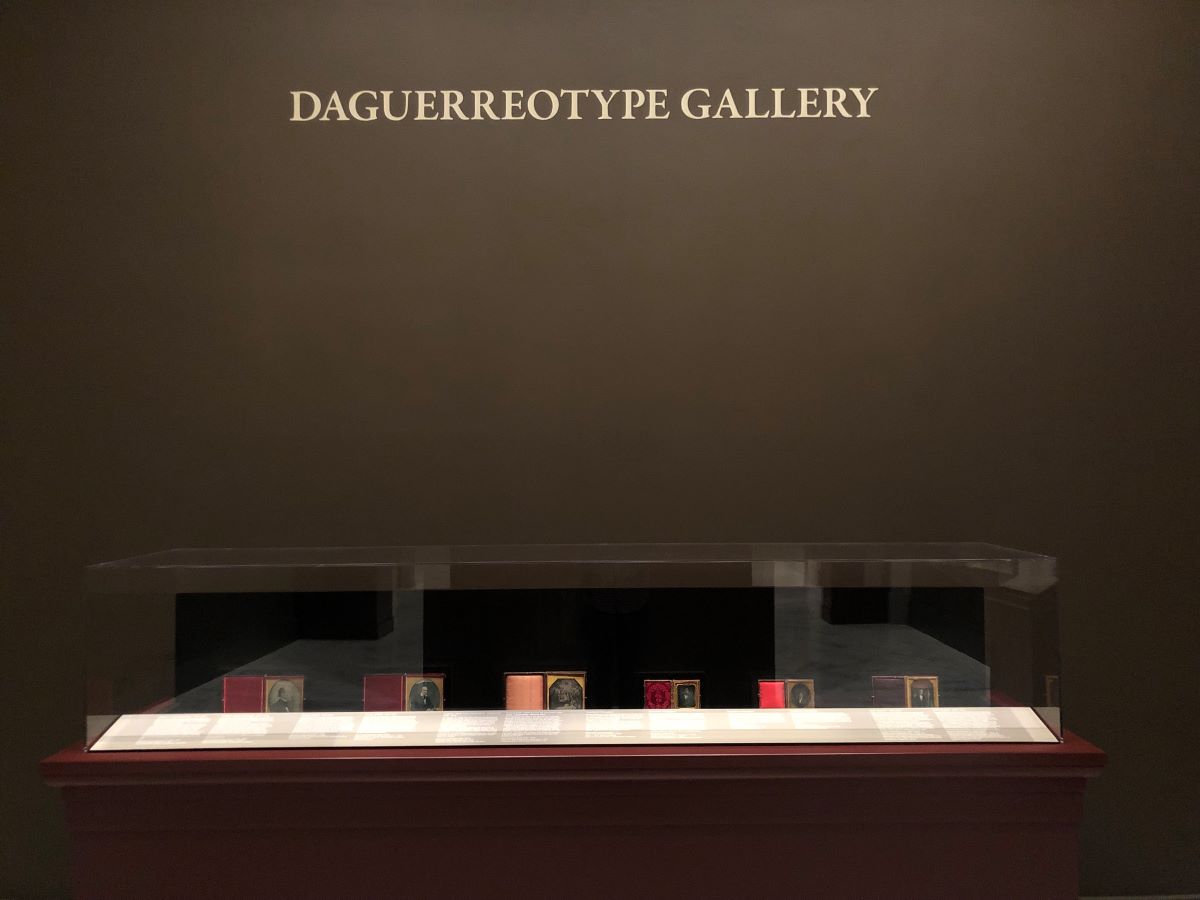

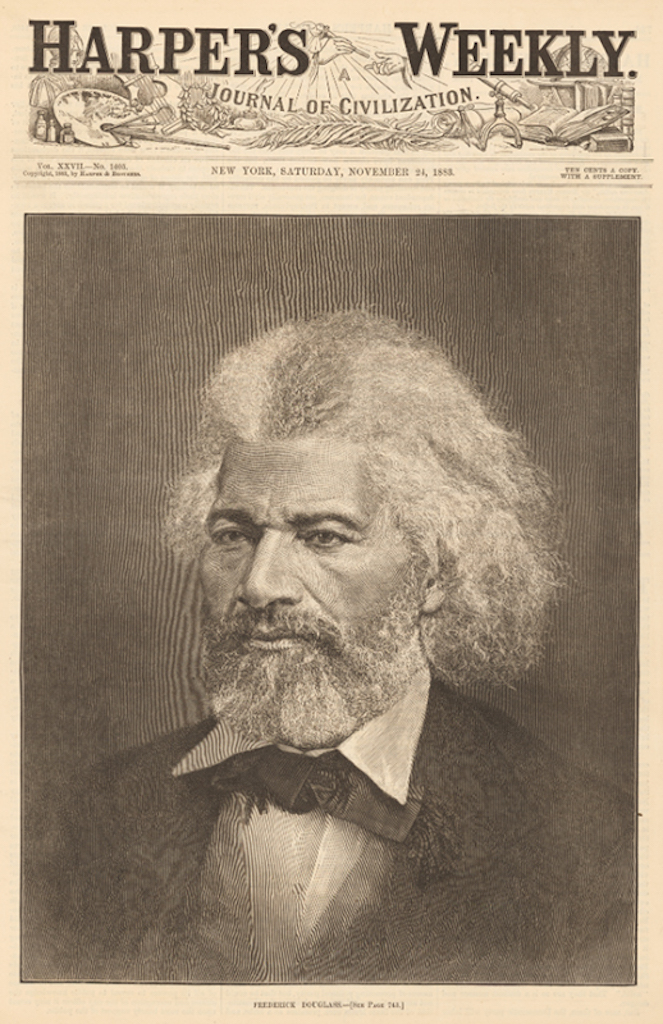

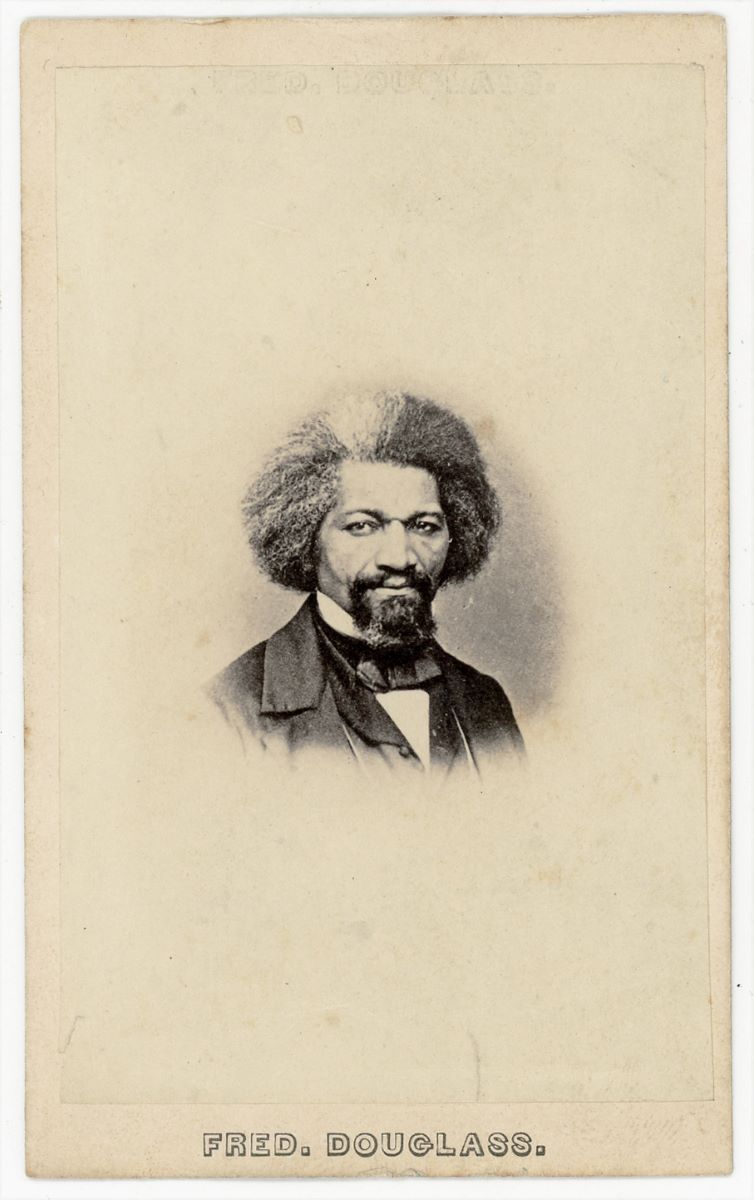

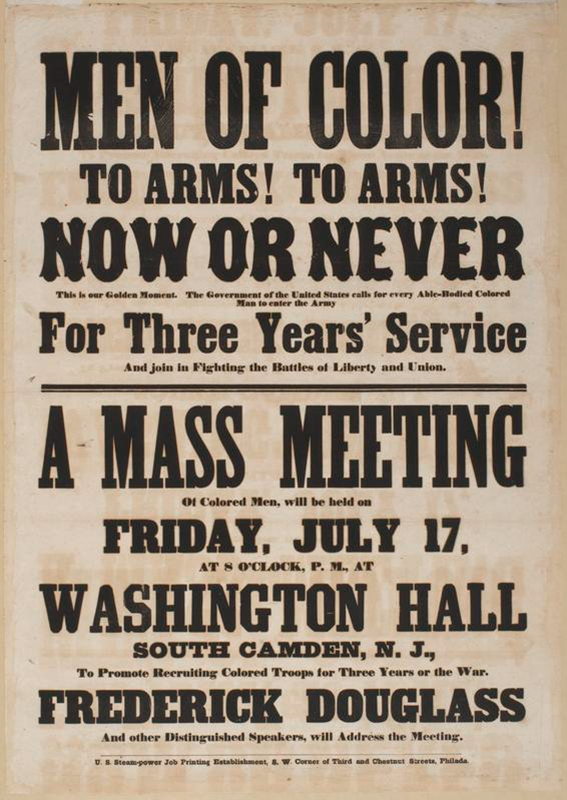

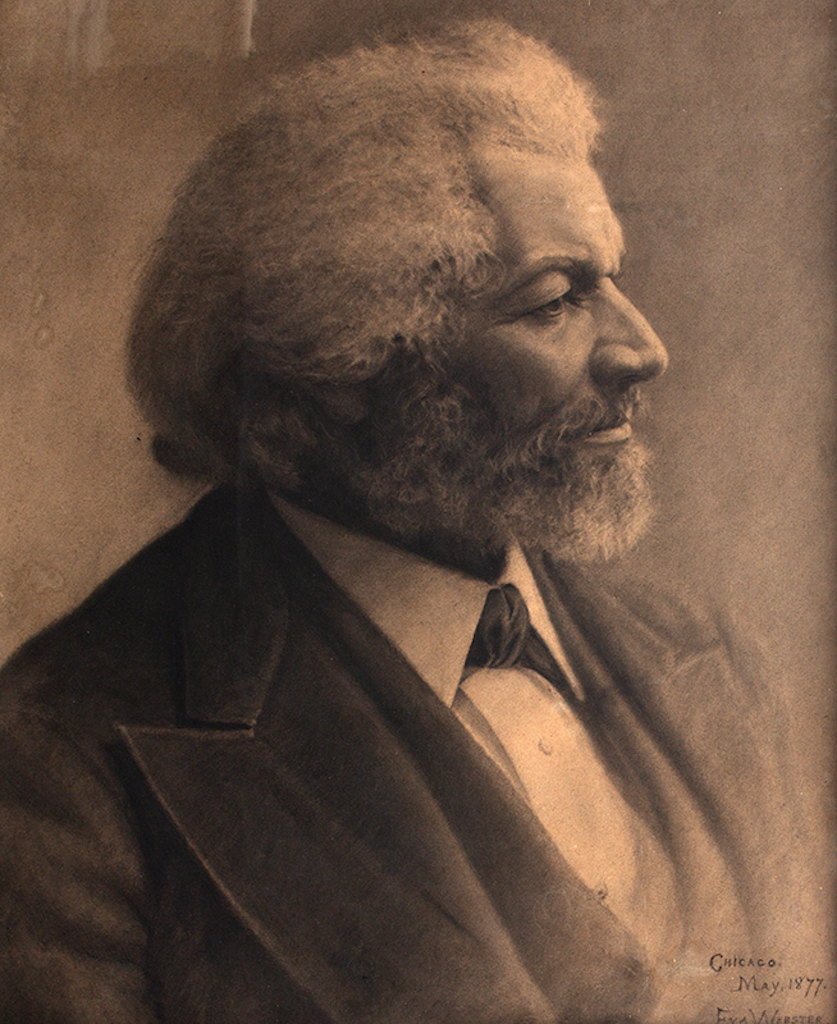

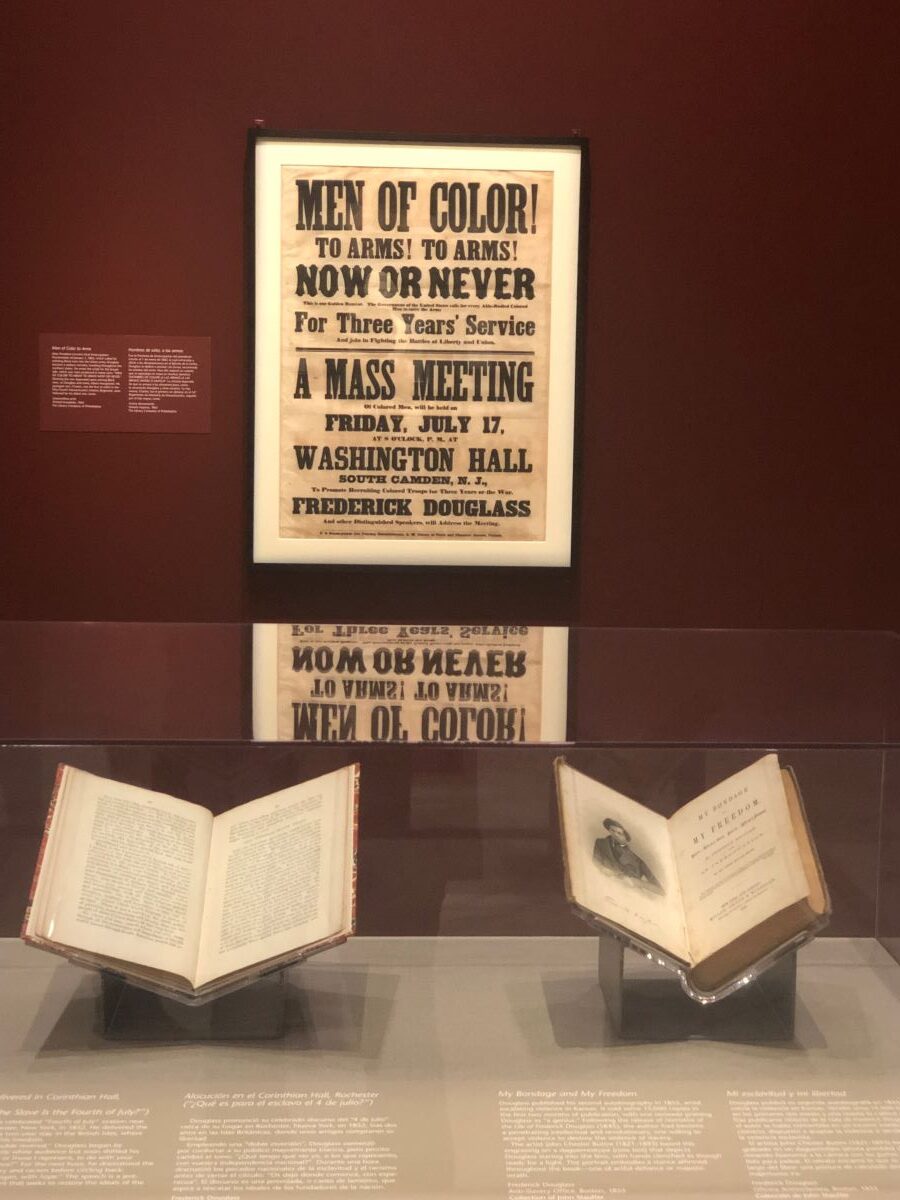

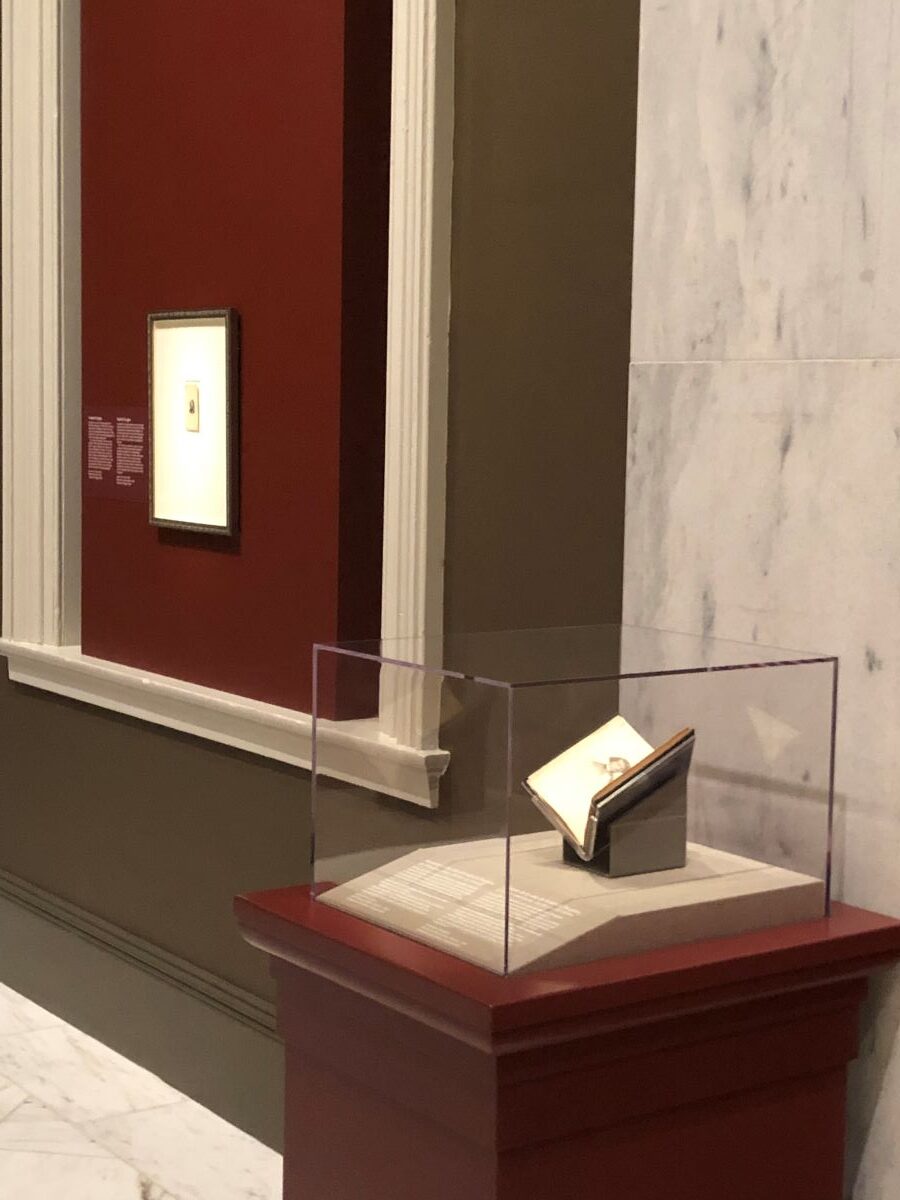

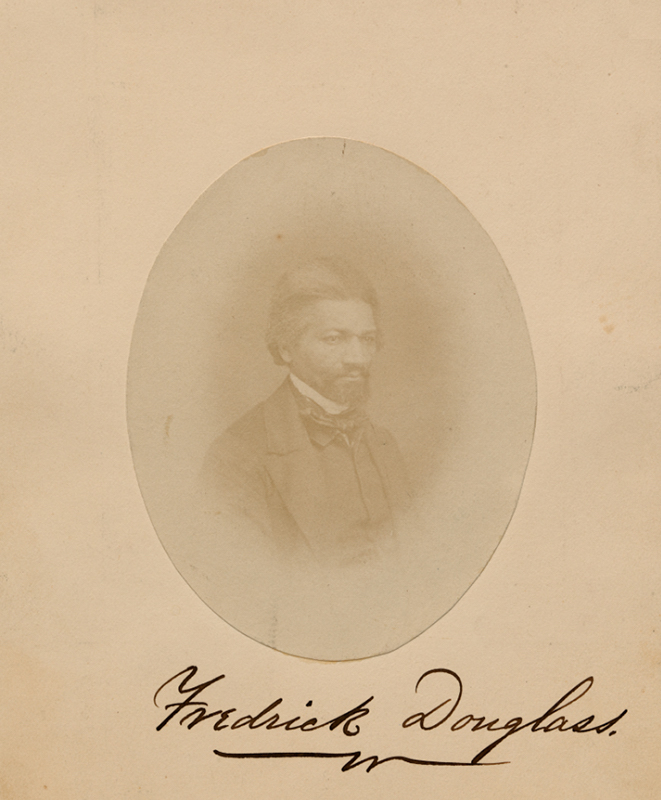

Frederick Douglass, the famous social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman, never knew the year of his birth. This was common for Black Americans born enslaved. And it followed, long after his death, the earliest detail about one of the most influential figures in our history could not be known to us either. Today, among the more than thirty-five historic objects to be seen in One Life: Frederick Douglass, a new exhibit opening this Juneteenth holiday weekend at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, is a recovered ledger recording Douglass’ birth in February, 1818.

When you visit the exhibition, the ledger is displayed open near the entrance to the gallery and is decidedly unsentimental, as it assumes its paradoxical place before the whole of an extraordinarily important collection. The ledger was discovered in 1980 by biographer, Dickson Preston and was kept by Aaron Anthony who managed the plantation of Edward Lloyd V, a US congressman, Maryland’s 13th governor, and Douglass’ first enslaver.

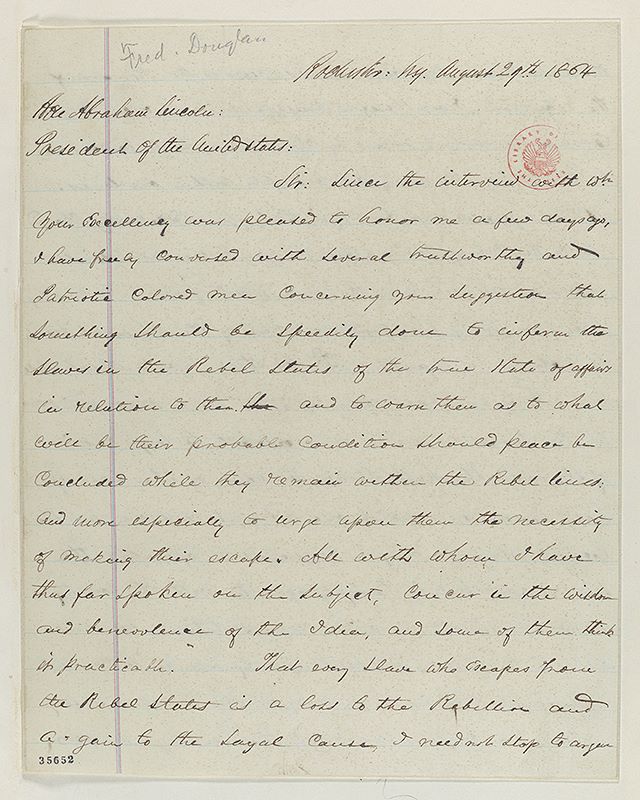

Douglass had been told his father was white, and suspected it was Anthony or Anthony’s son-in-law, Thomas Auld. But, as he wrote in his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave, “The means of knowing was withheld from me.” On the bottom of the left side page in Anthony’s ledger, Douglass’ mother is recorded briefly in an entry updating what was considered property: “Frederick Augustus, son of Harriet.”

Though Douglass knew his mother’s full name was Harriet Bailey, he was only allowed to see her four or five times in his life and explains, “My mother and I were separated when I was but an infant — before I knew her as my mother. It is a common custom, in the part of Maryland from which I ran away, to part children from their mothers at a very early age.“

The Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery’s exhibit, One Life: Frederick Douglass, curated by John Stauffer, the Sumner R. and Marshall S. Kates Professor of English and African and African American Studies at Harvard University, is the first Frederick Douglass exhibit the gallery has offered in decades and it is not only a must-see, but a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

According to consulting curator Ann Shumard, NPG’s senior curator of photographs, it offers significantly more than what could have come before this moment in time. Douglass, as a man, was continuously evolving, just as he fiercely advocated for societal evolution. On view until April 21, 2024, this exhibit reflects how our understanding of his legacy is ever moving forward as well. “History is never fully written,” says Shumard, “There is always another page.”