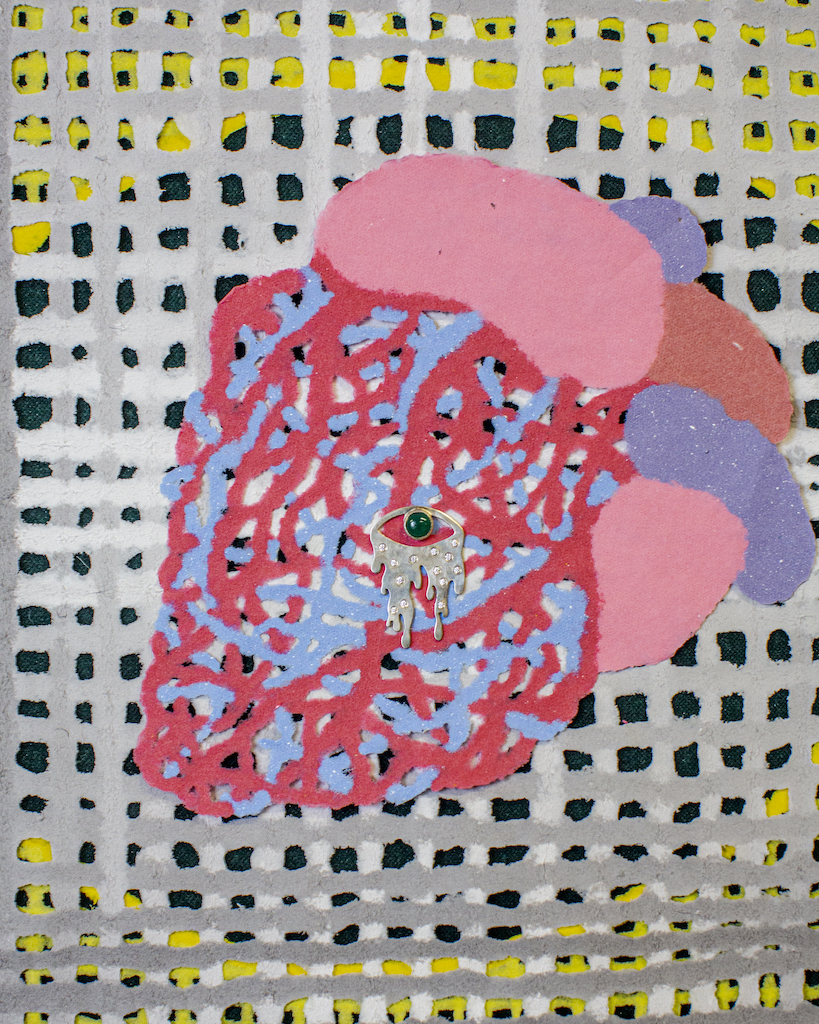

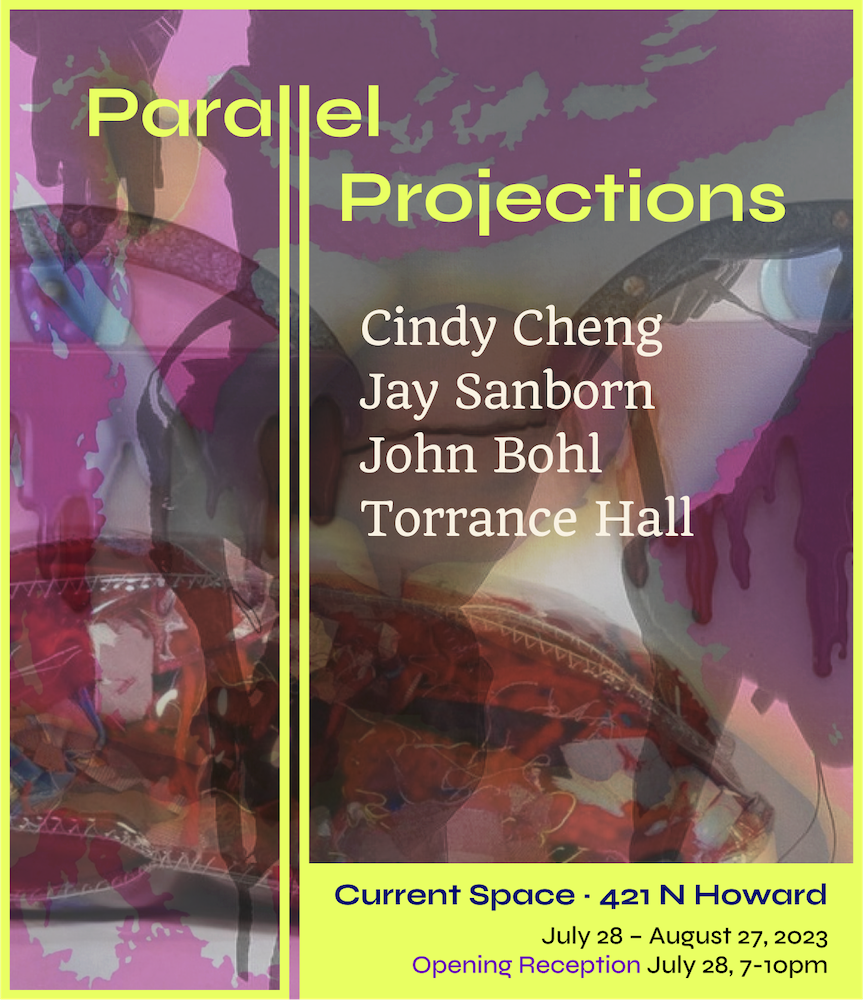

Cindy Cheng is fascinated by conspiracy theories. Born in Hong Kong and raised in Vancouver and Hawaii as a child, the Baltimore-based artist says her study of conspiracism helps her to better understand American culture. With equal parts worry and wonder, Cheng describes conspiracy theories’ growing pervasiveness in mainstream American society and beyond, noting recent scholarly studies that identify the United States a top exporter of conspiracy theories to the rest of world.

“They sound so absurd,” Cheng says, “but ideas from conspiracy culture have sort of become foundational myths.” Working in a range of diverse media, Cheng explores conspiracism as part of a broader American experience.

Growing up, Cheng attended a boarding high school in Hawaii—a place she describes as very different from mainland United States—and got her BFA at Mount Holyoke College before returning to Hong Kong for five years. At the encouragement of an undergraduate drawing professor, Cheng put together a portfolio while she was in Hong Kong and was accepted to MICA’s now-defunct post-baccalaureate certificate program in 2007. She subsequently earned her MFA at MICA’s Mount Royal School of Art and has been in Baltimore ever since.

Now a MICA drawing professor, Cheng has a flourishing art career in Baltimore. She won the Sondheim Prize in 2017 for her installations exploring the relationship between drawing and three-dimensional objects, and a year later, was awarded a Joan Mitchell Foundation Grant. Cheng was also a 2022 Joan Mitchell Resident. Her work has been exhibited widely in Baltimore, the US, and Canada, including at the Walters Art Museum, School 33 Art Center, Present Junction Gallery (Toronto), and, more recently, in the Baltimore Art Museum’s All Due Respect exhibition, which featured work by four Joan Mitchell Foundation Award recipients (LaToya Hobbs, Lauren Frances Adams, and Mequitta Ahuja).