“In Nigeria, your name is the first blessing your parents give you,” says photographer and video artist, Chuks. Chuks (pronounced, chew-ks) isn’t his only name. The artist also goes by Chukwudumebi (his birth name, which translates to, “God is with me”) and Gabriel, his baptized name. “They are all my name, I am all those people,” he explains.

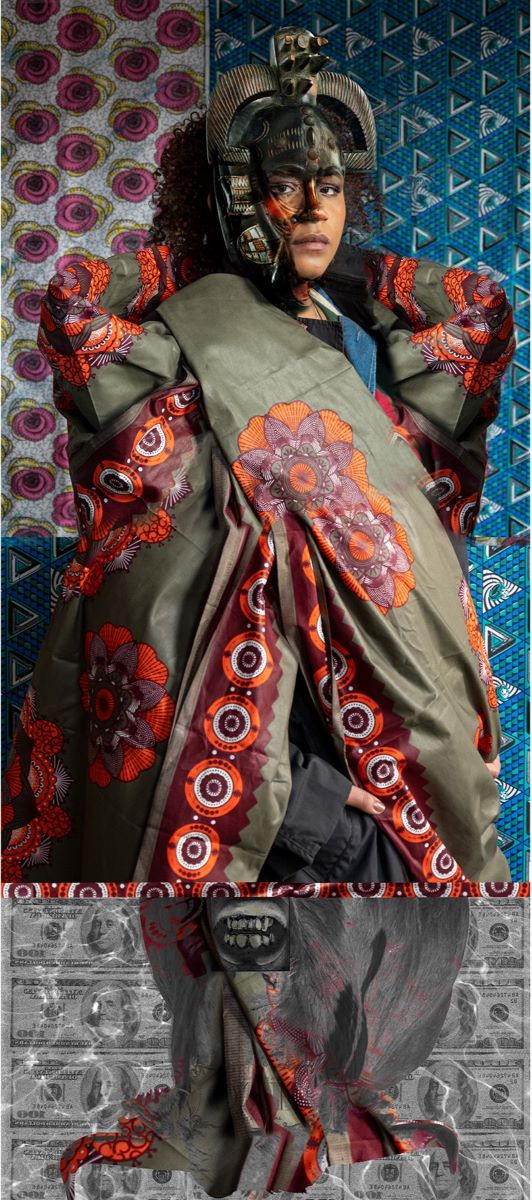

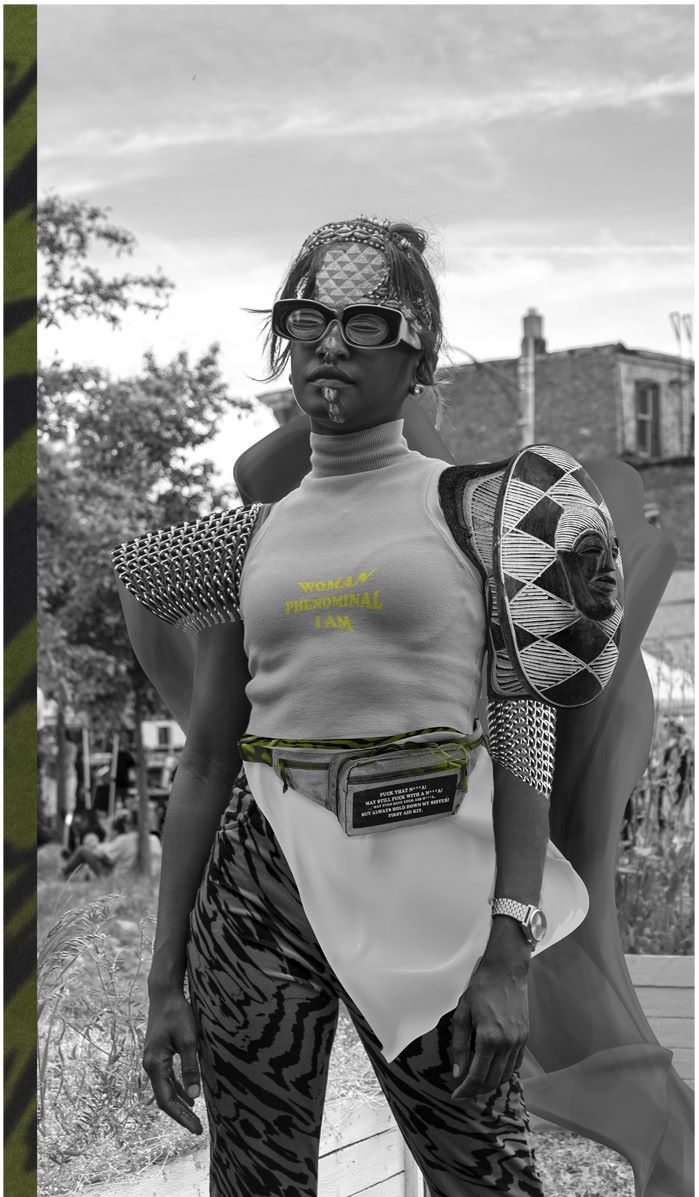

Like many artists, ‘identity’ is an underlying theme of Chuks’ photography. His dynamic portraits are synchronous explorations of self and subject. Chuks places particular emphasis on the past/present and individual/community. With a smile and a few anecdotes, the artist explains how he associates each of his names with a distinct period in his life. Yet his names also function as a unit: They “[reflect] my journey as an immigrant, artist, and Black man,” he says, collectively embodying the person he is today.

Originally from Lagos, Nigeria, Gabriel moved to the United States when he was fifteen. “At the time,” he recalls, “it was just my mom and I who immigrated.” His parents—both Nigerian, though from separate tribes (Igbo and Yoruba)—applied for US citizenship through the Diversity Immigrant Visa Lottery program before he was born. “Twenty years later, they get a call that we’ve been chosen for immigration.”

“Chosen” suggests good fortune, yet Gabriel describes his disinterest in leaving Nigeria: “I really didn’t want to go.” But go he did. First to Atlanta, Georgia, and eventually to Savannah, where he completed his bachelor’s degree. It was at this time that Gabriel experienced another life-altering transition, one that helped define the foundation of his artistic practice.