Standing in a flood of azure blue, a figure wearing a yellow t-shirt holds their arms aloft as if conducting an orchestra. Though one might expect the background figures to play instruments, they instead labor to lift objects from the flood, engaged in what might be disaster relief. Like many of Taha Heydari’s paintings, this canvas in his Federal Hill studio towers above my head. If a disaster persists across his work, it seems a fissure of orientation.

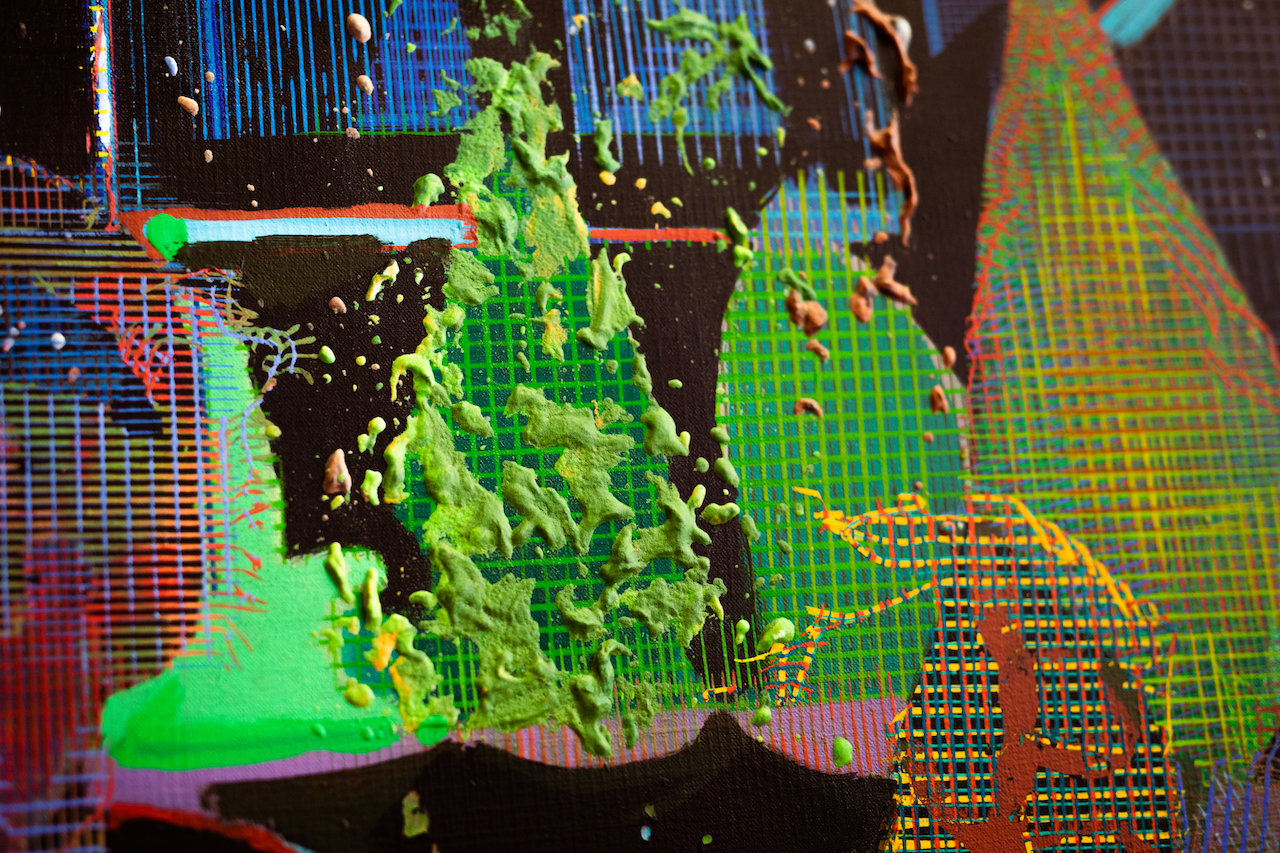

Heydari uses several tropes of fracture: bodies do not have definitive borders, facial features are indistinct or completely absent, and his hallmark grids that compose huge swaths of these large-scale paintings are torn and frayed at the edges. Though he paints in acrylic, his pieces initially look like mixed-media collage assembled with digital material. Consequently, these fractures read as glitches—and the fact that these glitches are physically created emphasizes how our material reality is just as precarious as our digital worlds. They are susceptible to transfer or corruption.

Born in Iran eight years after the country’s revolution, Heydari grew up in a tense political environment between Iran and Iraq. Then, the uprising of the Green Movement began during his last semester at the Art University of Tehran, and Heydari felt he and his generation were forced to create new identities. Heydari’s first solo show opened in 2009, coinciding with this freshly unsettled socio-political landscape.

By the time his second solo exhibition opened in 2011, he was frustrated with the shifts in Iran’s art scene. Collectors were leaving due to the economic downturn and increased sanctions, which signaled to the artist that it was also time for him to go.