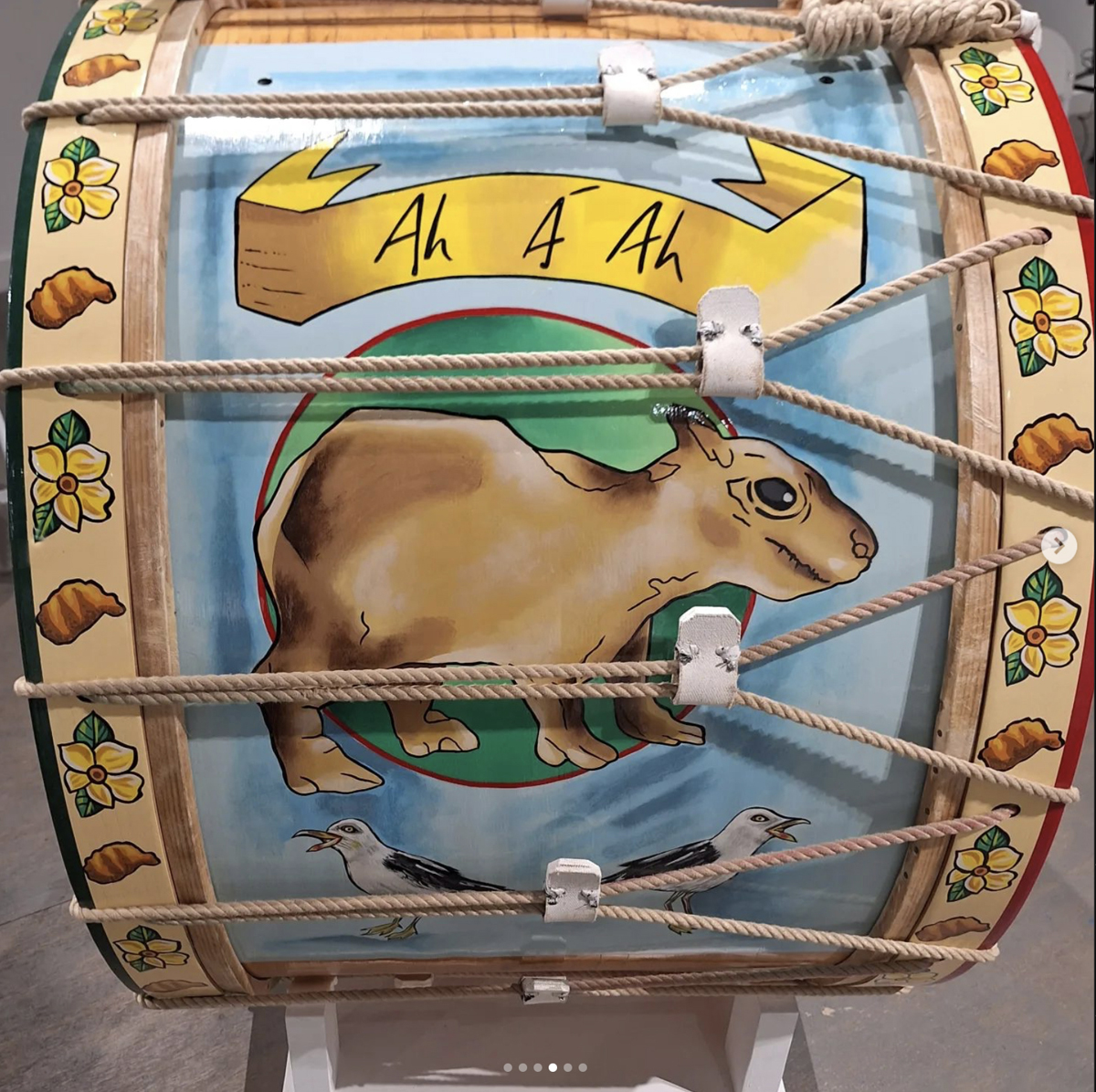

At the opening talk and performance for someone decides, hawk or dove at Stable Arts DC I found myself sitting beside a bronze cast of a pygmy hippopotamus and a seagull. Both creatures were solid black with beautiful textured surfaces. The gull had a shiny gold nugget in its mouth. In what was for the most part a fairly serious talk about the history of my home country’s divisions, I found myself laughing as Niamh McCann described the particularities of a Dubliner seagull’s character. They are virulent survivors that would snatch a steak out of your hand, she said.

Turns out the gold nugget in the seagull’s mouth is a chicken nugget. I laughed because I realized first of all that I had forgotten how cheeky those Dublin seagulls can be. In many ways all of the city’s residents are like this. There is an irreverence to the character of Dublin’s inhabitants that I have never found anywhere in the US. Not even in the toughest east coast cities—not even in Baltimore!

It’s in humor that we often find resilience, and McCann’s show is nothing if not resilient. The exhibit responds to the existence of a border on the island of Ireland between the North and South and the ongoing consequences and reverberations of this partition. It draws lines, maps territories, and above all focuses on intimate moments of humor and mythology. There is a tenderness in the midst of the fray. Combining sculpture, collage and video, the artist mines deep seams of the colonialist legacies of ‘The Troubles,’ a euphemistic term to describe the decades long sectarian violence dating back to the 1960s.

I first met Niamh last summer while she was in Baltimore and in the initial research phase of preparing for this show which opened September 7 at STABLE Arts in Washington DC. The show is from Solas Nua, DC’s premier Irish arts organization and McCann is their inaugural Norman Houston Multidisciplinary Award recipient. It was a delight to see their arts programming delivering the work of such a significant Irish artist. Politically and poetically speaking McCann’s work is a breath of fresh air flowing right into the heart of the nation’s capital. After a conversation at the opening, we decided to have an email exchange about the work.