Upon entry, the lobby diverges into two hallways that lead into themed galleries curated by genre and time period. After walking around the museum and experiencing all it has to offer, I can say the galleries I enjoyed the most are The Reach of the Gaze, Identity Values, and Reaffirmation and Changes. The first is dedicated to landscapes paintings, the second to physical manifestations of Puerto Rican customs and traditions, and the last is a comprehensive exposition on 90’s and 21st century multimedia art. These three gallery spaces encompass different aspects of the island, the natural environment we live in, our culture, and a perspective of the current social climate through the art we create. I cannot recommend these three exhibitions enough as they provide such a well rounded experience.

This museum is home to a wide variety of exquisite artwork made by Puerto Rican artists of all mediums and genres. While it has a plethora of art for visitors to see, I’ve decided to spotlight work that explores multiple facets of our culture for those who might not be familiar with it.

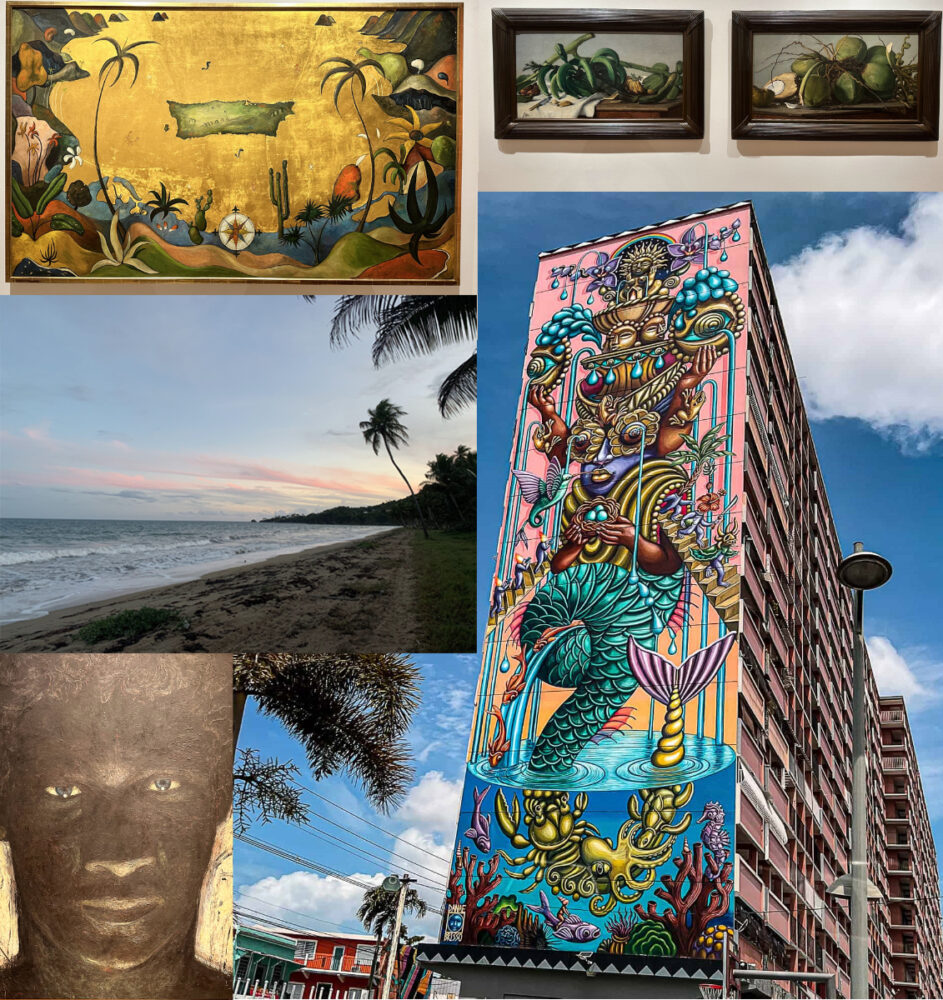

The landscape exhibition’s most notable work is a large acrylic on canvas, “The Last Mountain, El Yunque” by Jorge Zeno. The painting depicts the titular tropical rainforest, El Yunque, located in the northeastern coast of Puerto Rico and home to the island’s tallest waterfall. As one of the island’s top tourist destinations, I also have many memories of hikes and excursions taken through the forest, which always culminate by reaching the waterfall and taking a well deserved dip in its ice cold waters.

The vegigante masks displayed in Identity Values are a must-see. Vegigantes are a central figure in Puerto Rican culture with two distincts styles and backgrounds. In the northern city of Loíza, the masks are made of hollowed coconuts and are featured in the Catholic festival de Santiago Apóstol. In Ponce, a southern city, the masks are made out of papier-mâché and worn during the celebration of Carnival. In both festivities, vegigantes are mischievous characters that interact with the crowds and maintain the fun atmosphere of the activities. The display in the museum includes a great variety of masks made by artists from both Loiza and Ponce who have different aesthetics and styles.

The upper floor of the museum hosts Puerto Rico Plural, an exhibition that, as stated in the exhibition text, “combines work of artists from different generations, historical periods, and different media, with the aim of showing the plurality of Puerto Rican art from the eighteenth century to the present.” The exhibition displays emblematic artists including José Campeche and Francisco Oller as well as contemporary artists such as Jaime Suárez. Plural heralds the cultural, historical, and demographic differences of the island in order to share a true image of Puerto Rico’s diversity.