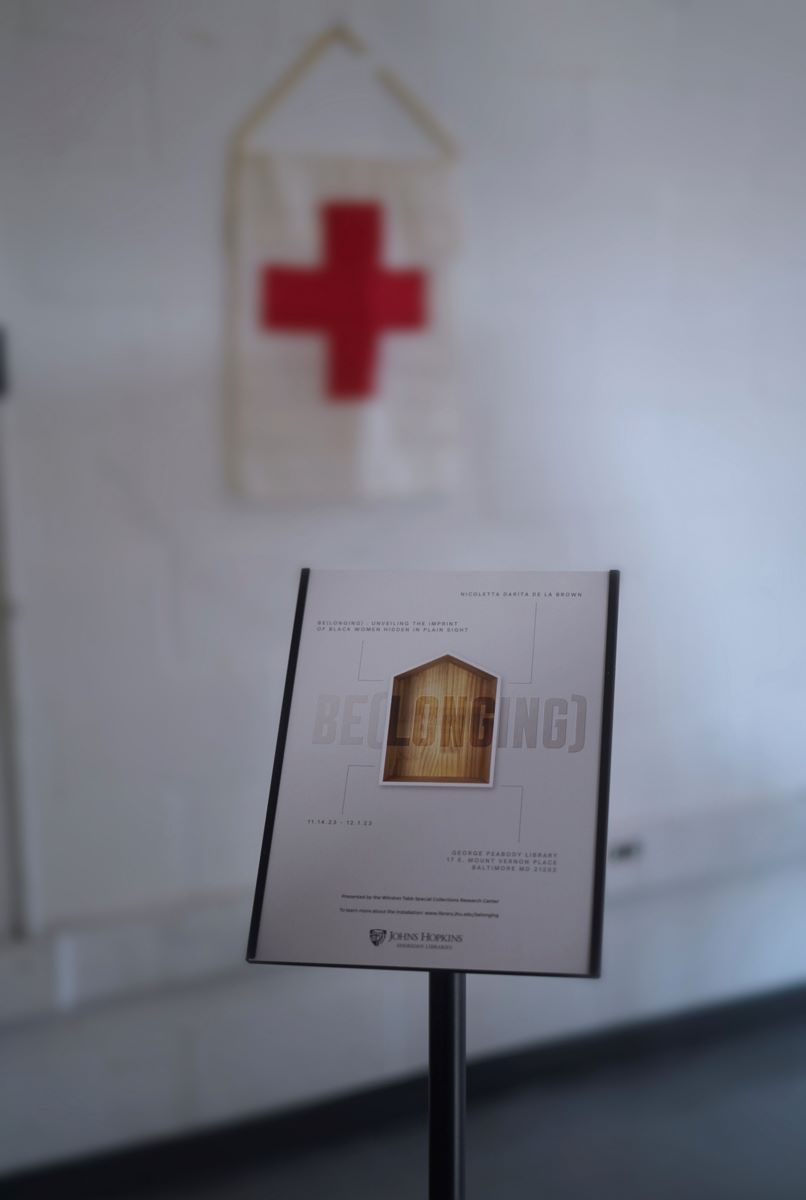

De la Brown, an interdisciplinary, experiential artist and chamána (shaman), has spent this year as one of two inaugural Public Humanities Fellows at the Winston Tabb Special Collections Research Center—part of the Johns Hopkins Sheridan Libraries & University Museums. (Hoesy Corona is the other. Corona will focus on expanding the Latinx collection and “mobilizing and remixing” what queer and Latinx materials currently exist.)

The fellowship, launched by Tabb Center Director Joseph Plaster, invites artists who are not otherwise affiliated with Hopkins into the university’s special collections and archives. Their directive: to creatively reinterpret and add to the collections.

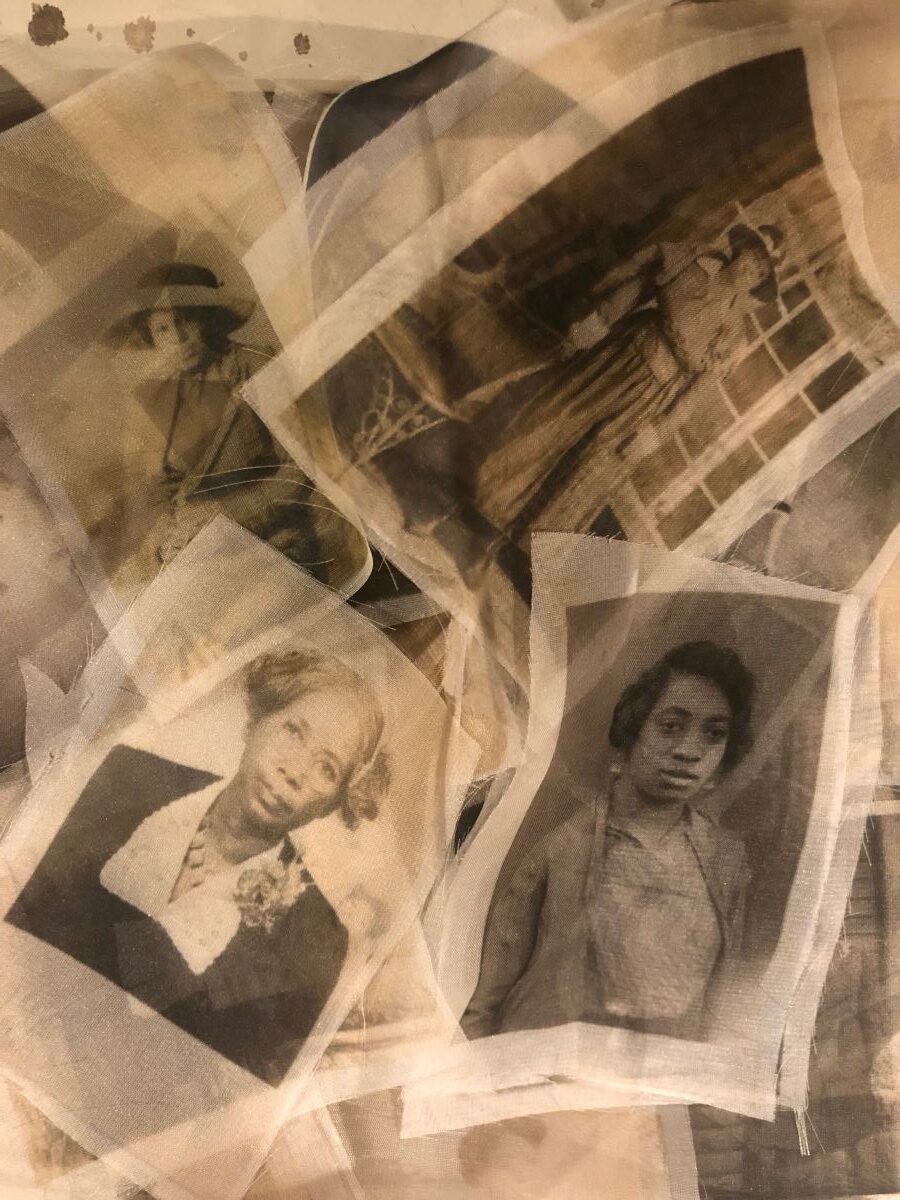

Beyond books and periodicals, the Sheridan Libraries offer a substantial variety of materials. In addition to the real photo postcards, de la Brown explored collections related to jazz singers Billie Holiday and Ethel Ennis, both born and raised in Baltimore. “I could touch objects Billie had touched,” she says. She found a photograph of Holiday at the age of four and a grocery list she had written on a small slip of paper, preparing to entertain friends for a holiday party. “I can identify with that, nourishing people through food. Thinking of Billie not just as an artist but as a woman, moved me.”

Ethel Ennis, who unlike Holiday spent the majority of her life in Baltimore, opened a cabaret and community space with her husband, Earl Arnett—which they called, Ethel’s Place. Just before Ennis passed away in 2019, the Sheridan Libraries acquired the couple’s archives, including VHS tapes of her performances, handwritten sheet music, historic photos, and ephemera from Ethel’s Place, among them a Baltimore Monopoly board game a friend had made for her.

“Ethel teaches me about boundaries,” de la Brown reflects. “She wanted a different path than Billie. After she recorded, she returned to her husband and kids. She came home. Two women chose two different ways to do it. For them it was music. For me, it’s experiential art.”

“Intellectually, artists pull from such a different place than a mathematician or a scientist might pull from. Even a historian,” says Tonika Berkley, Africana Archivist at the Sheridan Libraries. “For example, with the photo of Billie as a child, Nicoletta focused on her affinity to her and that was the connection she was able to establish. She brought in a photo of herself at the same age. And the style of the dress she was wearing was somewhat similar to the one Billie wore… That inspired her.”

In the first phase of de la Brown’s residency, Berkley guided her through the process of being in an archive, showed her how to touch the materials, and, in biweekly debriefings, provided company as de la Brown reflected.

“Tonika took such beautiful care of me as a person, in the same way she cared for the objects,” de la Brown says. “I could talk to her when things got tough, especially about Billie. It was scary working with such a big institution. I wondered, are they going to get it? Do I have to reduce down? But I didn’t. Because I had Tonika guarding the gate. She reminded me I could stay in my Blackness. ‘Stay you. We will adjust.’”

Berkley is also co-director of the Community Archives Program, a partnership between the Billie Holiday Center for Liberation Arts at Hopkins and the University of Baltimore’s Special Collections and Archives. Her work processing and preserving the university’s Africana collections is supported by Inheritance Baltimore, JHU’s Mellon-funded restorative justice initiative for humanities education and arts-based public engagement with Black Baltimore.