It wouldn’t be a show about early Modern women artists without the requisite paintings of Judith beheading Holofernes, and the Baltimore Museum of Art’s exhibition, Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400-1800 doesn’t disappoint.

The opening gallery pairs Artemisia Gentileschi’s Caravaggesque “Judith and Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes” (c. 1623-25) with Fede Galizia’s 16th century take on the topic alongside two other severed male heads: Luisa Roldán’s twin polychrome sculptures of Saint Paul and Saint John the Baptist. The effect is one of a lot of murder, by the literal hands of female artists.

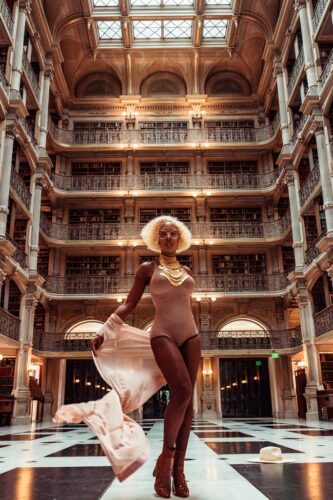

These stunning depictions of violence are nested in the first gallery of the exhibition, which welcomes the viewer with carmine red walls and works by some of the most famous women artists of the era, including Elisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun and Lavinia Fontana. Overall, you’re left with an impression of a kind of curatorial iconoclasm or an art historical joke about “killing your darlings” that is both funny and a bit on the nose. But what makes this opening gallery particularly interesting is that these canonical works of women’s art history surround an elegant centerpiece of 17th century lacework from the BMA’s own Cone Collection. From its very entrance, the exhibition whispers, “Come for the blockbusters but stay for the decorative art and material culture.”

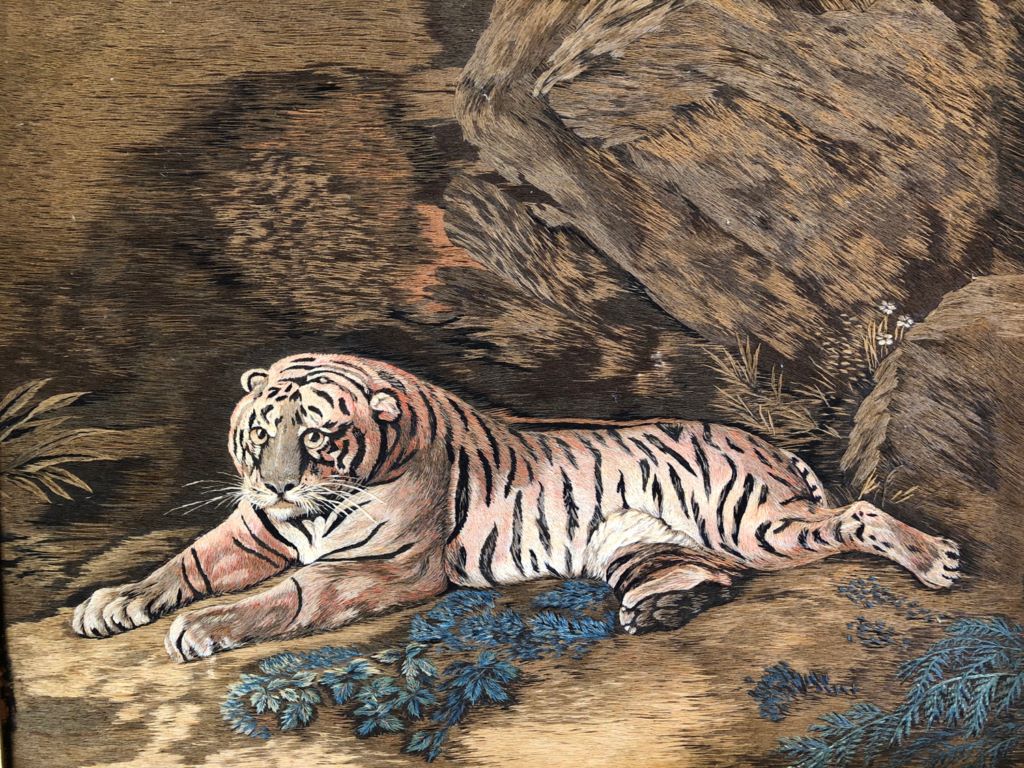

Co-curated by Andaleeb Badiee Banta, Senior Curator and Department Head, Prints, Drawings & Photographs at the BMA and Alexa Greist, Curator and R. Fraser Elliott Chair, Prints & Drawings at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Making Her Mark intentionally breaks down the categories of canonical art history, showing work by women from traditional high art disciplines like painting, drawing, and sculpture alongside often anonymous, or uncredited (and sometimes originally miscredited) works of decorative art, craft, and material culture like embroidery, paper-cutting, and lacemaking.