If you live in Baltimore City, there’s a chance one of Graham Coreil-Allen’s artworks has saved your life.

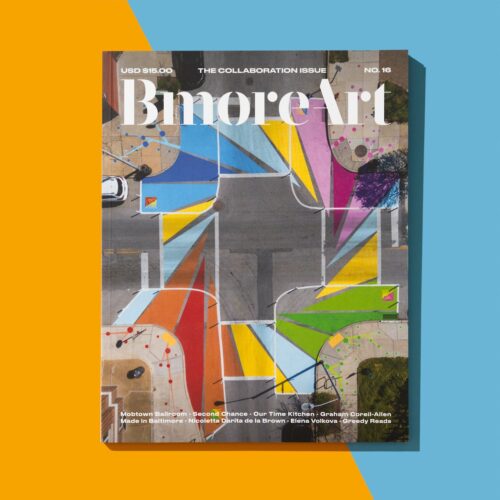

That sounds like the kind of hyperbolic praise some artists would receive for an emotionally uplifting painting or song. But Coreil-Allen’s collaborative “painting” practice—colorfully cascading across sidewalks, asphalt, and other infrastructure—is as much about the objective probability of preventing deaths as subjective aesthetics. Through his company Graham Projects, which offers a mix of urban design, public art, neighborhood advocacy, and placemaking services, Coreil-Allen and his team have transformed streets in Remington, Station North, Pigtown, Druid Hill, and beyond. Many of their projects are graphic, eye-catching murals designed to slow drivers down at intersections and reclaim a bit of public space from private vehicles, making the city safer, block by block.