Cara Ober: Looking at these images, I have to wonder – Were you raised Catholic? If not, what inspired you to incorporate Italian Renaissance style altarpiece paintings into your work?

Phyllis Plattner: I was NOT raised Catholic! (I am a nice jewish girl from Queens, though was raised and still am without any religious observance). The altarpiece format developed directly after having lived in Tuscany for a year while teaching in Florence and being constantly surrounded by altarpieces filled with Christian imagery and gold leaf. I’d also lived in Mexico for extended periods, again surrounded by similar imagery.

CO: Your paintings are immediately recognizeable, in terms of style, color, and content. To me, they remind me of Italian Renaissance and Gothic Cathedrals – the altar paintings. How long have you been working in this way? How did the process develop?

PP: I first started these paintings about 10 years ago (just before 9/11) with the paintings on the left side of the gallery— those that put into the altarpiece formats the little warrior dolls with ski masks and rifles and ammunition belts. The dolls were made by Mayan women in the state of Chiapas, Mexico, where there was an Indian uprising in 1994 when I happened to be there, and I had lived there several times previously over many years and was very deeply attached to the place. I began buying the dolls when I was there on several trips, finding them powerful little complex symbols, but didn’t start using them for my work till a few years later (about 2001) following the year I lived in Italy.

CO: When and why did you start using highly recognizeable, appropriated imagery in your work? How does your audience’s familiarity with the individual images create tension and surprise when viewing your work?

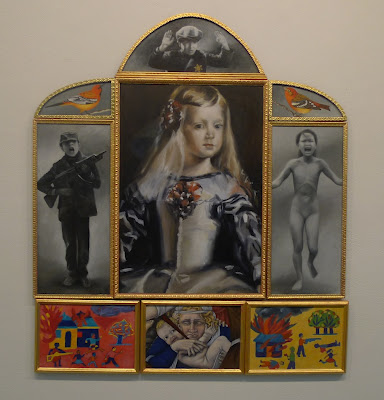

PP: There are really two related series in the show- the ones on the left called Legends (with the Mexican dolls) and the ones on the right called Chronicles of War. You’re asking about the appropriated imagery in Chronicles. The paintings (Legends too) are a response to my horror at the prevalence of war throughout human history. It’s depicted predictably as heroic and victorious in cultures all over the globe despite its unconscionable destruction and devastation. The fact of the plethora of these images that we see (in the paintings there are images from China, Japan, Iran, Greece, France, Spain, and on and on, as well as from many centuries, as well as contemporary news reportage) knocks me out, the accretion and the reiteration of them, the predictability of them. They chronicle war, and I chronicle the chronicling. I’m also trying to raise questions about who is a hero and who is a victim and who is a saint and who is a martyr. Hence my putting together the guy being lynched in the South, the Goya guy being executed, the man being tortured in Guantanamo, St. Sebastian shot through with arrows.

PP: Why do we teach that sainthood comes from human violence (the victim being the hero) but that we are heroes if we are victors and “win” a war, a conquest? The second part of your question– about the audience’s familiarity with the individual images-with random people (friends) wandering in and out of my studio I find that some are familiar with some of the images and some are not (not all of us, even educated ones, are art historians!). But yes, these paintings (whether or not the specific images are recognized) create tension, discomfort, question, thoughts.

CO: What is your own political stance on war and violence? Do your own personal views shape the way you combine imagery or is your desire to present a kind of skewed mirror of history and current events, without a specific narrative or judgement?

PP: My stand against war is very strong. In the paintings I am contrasting the warfare imagery with its opposite– babies, angels, putti, bucolic landscapes, ethnic patterns and designs, the gold leaf itself, the skyscapes, even the altarpiece formats– as a reference to the other side of us complex human beings, the healthy peaceful side, you might even say the truly “religious” or spiritual side— in contrast to the fact that so much war is fought under the auspices of religion, a fact that I find incomprehensible in any true meaning of “religious”. I am also highlighting this in the paintings.

CO: Who are your favorite artists? What are your other influences?

PP: My influences have been more my experiences living in other cultures, particularly underdeveloped ones but of course, Italy too. My husband is an anthropologist and his research has taken us to many fascinating, wondrous places to live. Chronicles started after a personally earthshaking experience I had in Beijing, making me aware of the enormity of the world population and the incredible vulnerability and fragility of each individual. Why in the face of that do we kill each other?