The Illustrated Novella Land Beast: An Interview with Kate Wyer and Katie Feild by Michael B. Tager

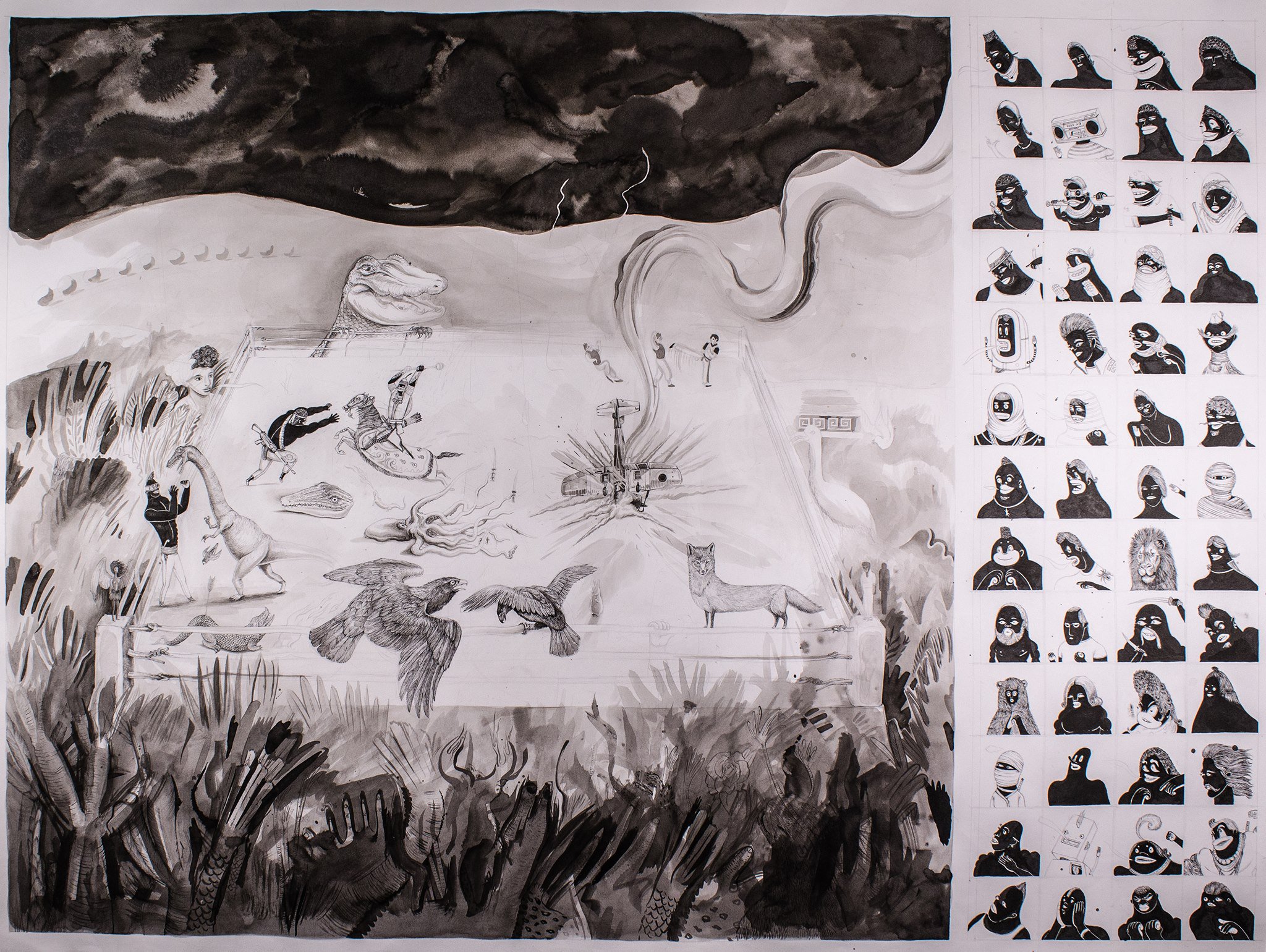

In 2015, Kate Wyer and Katie Feild debuted a beautiful, odd book called Land Beast. Hearing them read portions of it and seeing the images that were created in accompaniment made me question what a book could be and why the creation of a book is important. The novella is short and sparse, with images throughout that are evocative and just-short of explicable. I had to know more about the book and about its creation, so I reached out to the creators for more information.

Top Image: Kate Wyer, L and Katie Feild, R

How did Land Beast initially come about?

Kate: Land Beast was originally published in The Collagist. Matt Bell was still the editor then, and I took a chance on sending him this strange, hybrid-y story told from the perspective of a wounded, grieving beast.

Katie: I first read Land Beast as it appeared in The Collagist. After reading it, I had no idea who the narrator was. I thought it might be a made-up beast undergoing some evolution (that it was telling its tale of its evolutionary catalyst). I liked not knowing for sure. A little while later, the second part was available and it still was never stated—that we [the narrator] were a rhinoceros.

Kate: Katie’s right—I never reveal who is speaking, just that it is a mother who has lost her child to violence. I chose to omit naming the beast because I wanted to make it more universal. I was also a bit nervous about owning the fact that I had written in an animal’s voice. When Matt was leaving, he asked me to send him a story for his last issue. In the second part, I’m a little more specific about what kind of beast is speaking.

Once both parts were out in the world, I realized that I could turn them into a book, and with that book I could raise money to fund anti-poaching organizations. If I had started with that purpose, I don’t know if I could have written as freely.

Without Katie’s partnership, the book never would have been a reality, and money would not have been raised for the International Rhino Foundation. I was so thrilled with Katie’s design of my novel, Black Krim, that I was overjoyed to partner with her again.

Why did it make sense for a visual artist get involved?

Katie: We had collaborated a bit before this project, on her book Black Krim, published by Cobalt Press. We designed the cover of that book [and we also] worked together on the interior where symbol illustrations are used to represent three narrators.

Kate: We originally met at UB’s Creative Writing and Publishing Arts program.

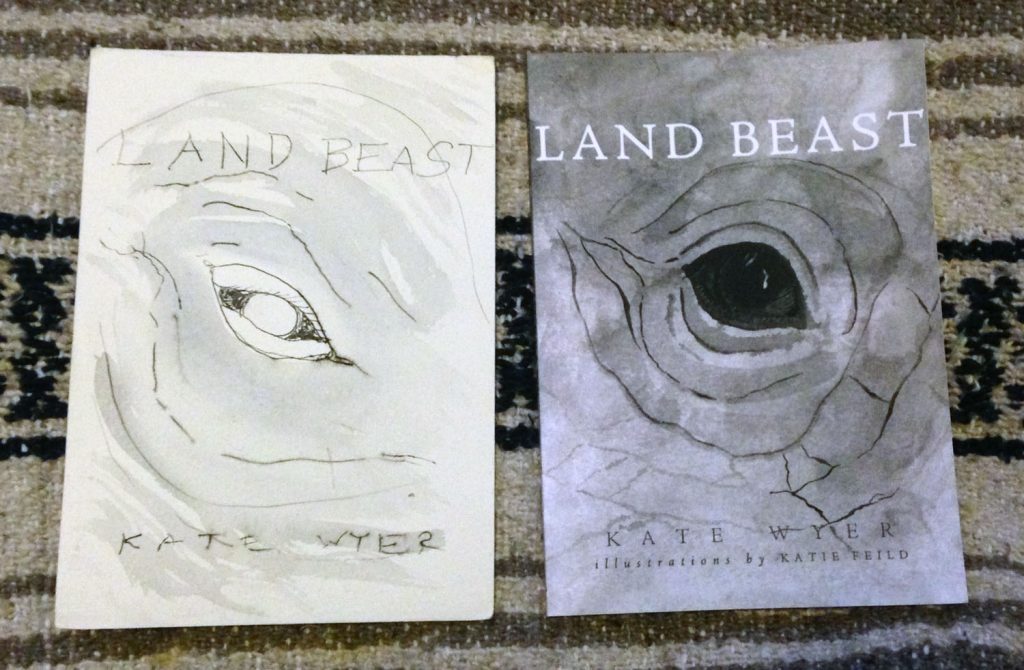

Katie: [Kate] had a vision of an eye for the cover. She asked if I was interested [in creating the cover], and that was it! She seemed to really like the idea of adding art. I mentioned maybe she could get many artists’ illustrations in there, with each artist’s own idea of who the narrator was. But she pointed out, “Katie, you could do the illustrations!”

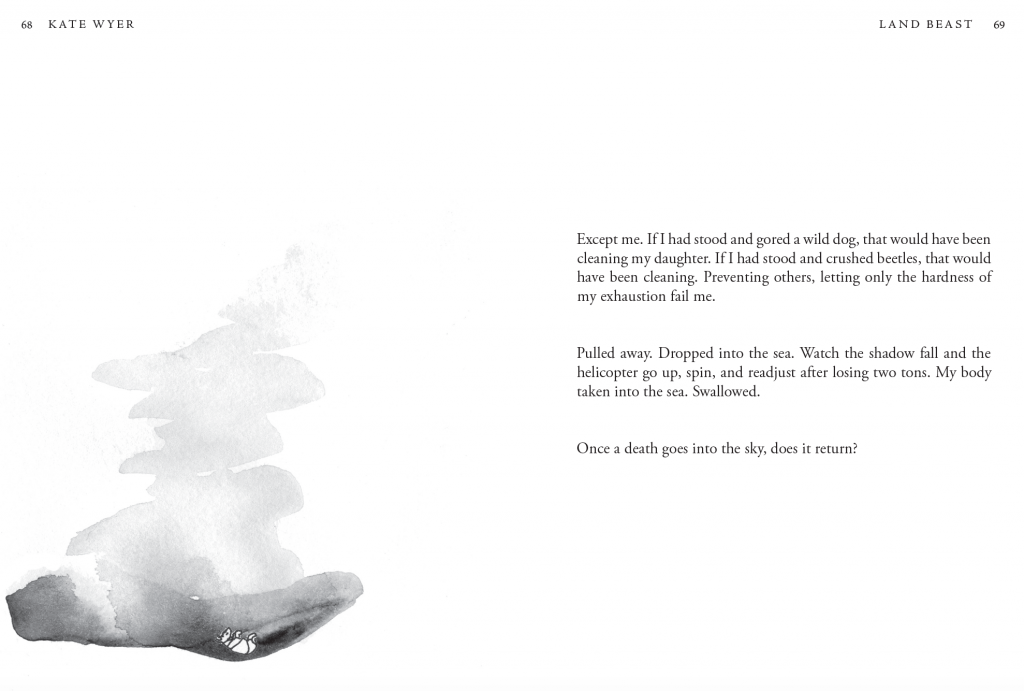

Kate: I loved Katie’s small illustrations for Black Krim, and when we were first brainstorming, I knew I wanted at least some small sketches throughout. I didn’t have a concept, other then the eye Katie mentioned. The total number of illustrations came about because of the page breaks that Katie intuited. She took my lines and paragraphs and found places to pause, to settle, to sink. These became page breaks instead of white space on the page.

Katie: The stories were very cleanly formatted on-line. There were some paragraph breaks, but for the most part, the story was presented on a single web page, no navigation or next-page interruptions. There were no pictures or visuals. Just text. I like that simplicity, especially when the obvious is not stated (in this instance, the narrator being a rhinoceros).

In the move to print, a number of considerations arose…how will the text look? How to format? What is the pace? How will the look affect the pace? How many pages will it span? How should it feel in the reader’s hands?

Kate: We then went over the themes, in a storyboard way, that each page presented. She achieved an atmospheric resonance with the use of watercolor. They are surreal, float-y, and full of emotion. There is a dreamlike quality to them—which is very much in keeping with the story. I had a friend tell me they felt like they were reading a fever dream when they read Land Beast.

Katie: I imagined the book itself as the rhino and placed an eye on the back cover as well. The reader enters the story through the eyes of this rhino—the pages represent its horn. the horn’s impact on perspective—the most valued aspect of the rhino and the thing that had been taken from it. What was missing could be found in those pages.

A cover is only the container of the book—the story itself, if formatted the way it had been on-line, would either result is a large-sized book to fit the length of each part, or would now be broken up into pages. It would remain a straightforward read, but wouldn’t fully utilize the potential of printed text.

We decided to print this book as similarly as possible to Black Krim so that they could act as a collection. That drove our book’s dimensions, and printing parameters and also determined that the illustrations would be printed in black and white. Ideas shift and change with limitations.

There were no illustrations yet, but the inserted pages were paced facing text on every page turn. That is when I recovered my love for brush-painting and used that technique with watercolor and my illustrative tendencies to produce more representative symbols and conceptual threads to carry the visuals and amplify the text.

Holes are a theme. Even the moon is a hole. The horn is a hole.

The eye is a theme. And what the eye sees. It is deep and hole-like too.

What I did not expect to do was reveal the narrator. Once I let go of my stubborn intent to maintain that mystery, it opened up the reality of that being. I nervously pointed out to Kate that once my illustrations were added, they would show that the land beast is a rhinoceros. There would no longer be that uncertainty. Kate said she was good with revealing the rhino, that it was time the story took its next evolutionary step.

It sounds like an authentic collaborative process with writer and artist guiding and inspiring one another. How did that work?

Kate: We met a few times, but Katie mostly worked on her own. We went over her paintings and were able to make real-time edits on a few. The illustrations you see are actually very layered and sophisticated collages of many small watercolors. She’s a master digital designer, and I was thrilled to see the images she painted translated into these pages. The tweaks were small—make the rhino a little larger, or make the texture appear a little darker, etc. The whole time we worked together, I was very grateful to have someone so dedicated and so willing to really collaborate.

Katie: When Kate found something worked, she would say so and point out any changes to make. If nothing presented seemed right, we’d start over!

Land Beast went so smoothly and quickly—I don’t think there were as many obstacles as can happen.

You talk of obstacles that didn’t occur. Was the collaboration a daunting prospect? Did it improve the work?

Kate: The collaboration evolved the work. I feel like it was able to reach another level of consciousness by having the visual element. I think the page breaks strengthen the story, because they slow it down a lot. There is so much emotion in it, that having the breaks allows both a relief, and a way for the impact of loss to actually sink in too.

The chosen layout of the book meant Katie’s contribution was going to be presented in concert with the story—it wasn’t going to be behind the scenes. This prospect was exciting, and not daunting. I could see it being so if I didn’t know and trust Katie so much. I know her sensibilities, and her influences, and I know she thrives off of the exchange of feedback. I felt I could be honest if something wasn’t quite what I imagined, and didn’t fear losing a friend and creative partner. I knew she wanted that dialogue. I couldn’t wait to see how her brain processed the story, and how she translated that to images.

I guess I like giving up control in that respect. My stories tend to be very minimalist. That’s intentional—I prefer to allow the reader to fill in the gaps, and for them to be a part of the creative process. I, for one, cannot stand when an author spells everything out for the reader. I feel the mystery of putting words on pages, words that creates images in the brain of another person, is a kind of magic. Authors should get out of the way of that magic as much as possible.

It sounds like you feed on this kind of collaboration. You’re also collaborating on a reading series. Can you speak to that and to your roles?

Kate: I met Maya, the driving force behind the Amplified Cactus series, as a Goucher alum. I believe I invited Katie along to meet Maya for lunch or something—it’s a bit fuzzy. The series is multi-media, and it’s producing new work for each show in response to prompts tangentially connected to John Cage’s piece of the same name. There are poets, fiction writers, experimental musicians, painters, and photographers. There will be dancers in the spring.

And yes, amplified cacti!

Katie: Ah! Amplified Cactus. That art/music/writing/performance series burst into being with Maya Alexandri as primary catalyst. I format, print, fold and bind chapbooks presented at each event. there are six total events—3 took place this past fall, and 3 more events are expected in spring. All 6 chapbooks have expandable spines that fold onto each other and combine into a paper cactus sculpture.

Come out and see what it is!

You seem really interested in multi-media experiences. Do you think the general public is as interested in illustrated books like Land Beast? How are illustrated books different from, say, comic books or children’s picture books?

Katie: At the time [of Land Beast], I had revisited and been inspired by Neil Gaiman’s and Yoshitaka Amano’s The Sandman: The Dreamhunters. Gorgeous atmospheric art opposite written story. But I also showed [Kate] an example of inserted art/photography via vellum in Richard Bach’s Jonathan Livingston Seagull.

I tend to think about how text relates to or coincides with the art and what element is carrying the bulk or weight of the story, and how that story is delivered (and who it is for). Comic books can show what text does not show, the visuals perhaps primarily carry the story. This seems the same with graphic novels, where text does not have to be as volumed as image, or the image is impactful or insightful in ways text is not with how a story wants to be told.

I’m not sure I agree that there should be a genre called children’s books, only because I feel adults can or should enjoy and learn from books that are set aside in this category. What I can say in confidence is that books with images and text are not delegated to youth. Image requires as much reading and literacy (if not more in some cases) as text.

My equation would be, so long as there are people, there will be some number of them that like drawing and telling stories, and those that like to read them. And since there are more people in the world, and more tools/accessibility for publishing, I can imagine there are more illustrated books now more than ever.

At least I hope there are…

How did the illustrations—or having profits go to charity—affect sales?

Katie: When Kate came to me about the book, she told me that she wanted all profit to go to charities that help protect rhinos. She also wanted to publish the book in time for international rhino day. That gave us a tight timeframe (I think it was about one month—wowsas!), but was essential for visibility of the book as a means for charity—journals and charities could boost the novel by posting about it on that day when more people are rhino-aware, and that boost in sales goes right into the charity.

Kate: Writing Land Beast was a very emotional process. I had been waking up to the image that inspired the story—that picture of the brutalized face of a female rhino. The story is perhaps the most raw and vulnerable thing I have ever written. I couldn’t image profiting from the story(the events of which are based on a real rhino and her calf), and I felt powerless in changing the world economies that drive the poaching industry. The most I could hope for was to support the people who were willing to at times put their own lives on the line to protect other beings.

Right from the start, all profits were going to go to vetted organizations. That decision was my response to the question “What can art do?” I had made this work as a cry of rage, frustration and depression—but did that change anything? When I first wrote it, I wasn’t looking to directly save rhinos, but as the stories stood in the world, I wanted them to make a measurable impact.

In the less magical realm of marketing, having so much new content was something I could highlight. Parts I and II of Land Beast were available for free, online. Adding the epilogue, and having the illustrations created a draw for the people who had already read the stories. That was my hope, anyway.

Sales were driven by a number of things: the first being the essay I wrote for The Elephant Journal. It’s basically the origin story of the book, and in it I describe what I think art can do in/for the wider world. The second was partnering with Lydia Millet, the Pulitzer-prize finalist novelist. She works for The Center for Biological Diversity, so I took a chance and sent her the manuscript, asking her to promote it with an email blast to the members. Lydia was very generous and kind. She was able to include info about the book in the monthly update.

My continued partnership with the International Rhino Foundation has been so gratifying. They work hard to promote their partner artists, and are creative in featuring the work that community is doing. I believe that the fact that all proceeds are donated definitely helped drive sales in the markets I mentioned. After the initial splash from The Elephant Journal and The Center for Biological Diversity, most of my website traffic is now driven from links on The International Rhino Foundation.

That’s a really positive way to drive traffic. Speaking of which, is there anything you’re working on now?

Katie: I have plans to publish an illustrated short-work of my own (it’s called Holy Borges).

Kate: I am working on a novel about a homeless woman who lives in the drainage runoff basin of a suburban development.

**********

Author Michael B. Tager is a Baltimore-based writer and editor with a reasonable wariness of bears. You can read more of his work at his website: Michaelbtager.com.

Kate Wyer is the author of the novel Black Krim, which was nominated for the Debut-litzer from Late Night Library. Her manuscript, Girl, Cow, is a finalist for the Omnidawn Fabulist Fiction Chapbook Contest. Wyer’s work can be found in The Collagist, Unsaid, PANK, Necessary Fiction, Exquisite Corpse, and other journals. She attended the Summer Literary Seminars in Lithuania on a fellowship from FENCE. Wyer lives in Baltimore and works in the public mental health system. katewyer.wordpress.com

Katie Feild has been living in Bflat7 for years, and is approximately Gflat7 in height (though some days she springs to Fmajor). at times, her hair is ferocious. she treats each project she meets like a person. she loves love, and works and plays like the rest of you. and she’d prefer to hear all about yourself. katiefeild.com

Find out more about the novel at the Land Beast Website.