This week: Crossover at Gallery CA explores complexities of Chinese identities, Woven Words: Decoding the Silk Book at the Walters breaks down the weaving mechanism that helped create a rare silk book, and Sylvie van Helden and Sharon Servilio distill lived experiences into meditational compositions at Loyola’s Julio Gallery.

The Friday Gallery Roundup is a curated compilation of three short reviews of three current exhibitions worth your time and consideration. There’s so much to see and do in this town every day—check out our calendar and weekly picks for even more options—but here’s a doable list of shows you can check out now.

Crossover, through March 26

Gallery CA, 440 E. Oliver St., Baltimore, 21202

Hours: Monday–Friday noon–4 p.m.; by appointment

At the gallery’s main entrance, Beth Lo’s slip-cast porcelain figures hanging on the wall introduce this show with a confrontation. Five small children, their bodies gray and their facial features smudged smooth, stand below speech bubbles that contain various flesh-toned silhouettes of the United States. On the left, a sixth figure, fully painted, waves a white flag with the universal red and white “do not enter” symbol—the children messengers of a warning that skin that isn’t alabaster is not welcome in this country.

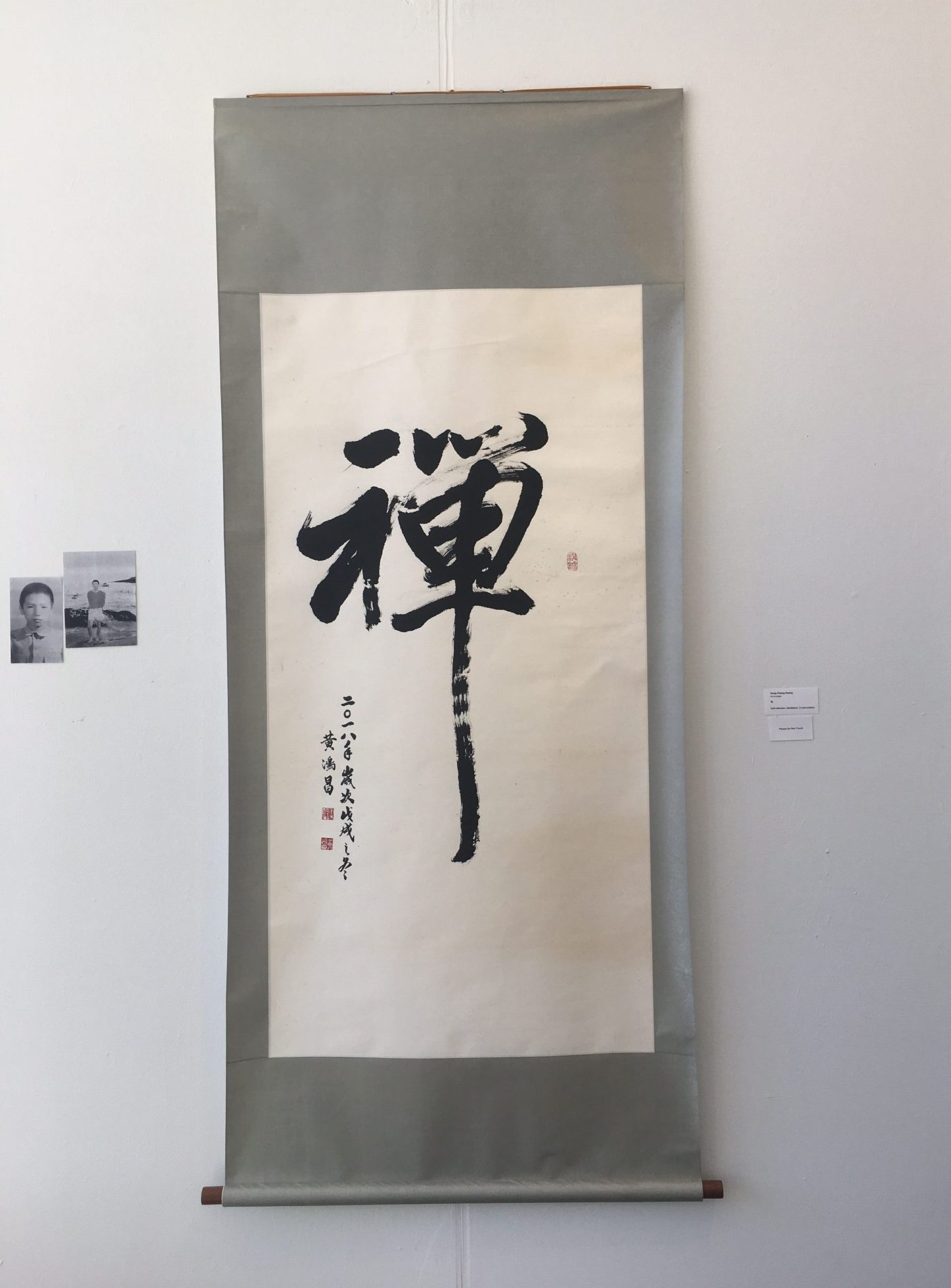

The show, curated by MICA Curatorial Practice MFA candidate Tracey Jen, expands upon diasporic themes of (be)longing, identity, alienation, assimilation and more through the paintings, ceramics, and calligraphic works of Beth Lo, Hung-Chang Huang, Sicheng Wang, and Adam Chau, each of Chinese descent. Hung-Chang Huang’s large scrolls monumentalize the art of Chinese calligraphy; you can feel the gesture and weight of each mark dipped and dragged around the paper by the artist’s hand—you can also watch a video of the artist at work on a scroll at his desk. In contrast, another video shows a calligraphy machine daubing glaze on iPad-shaped ceramic slabs creating a programmed self-portrait of artist Adam Chau. Of course something is lost when a machine takes the brush, but Chau’s work accepts this reality, forcing a tension between that and the double-edged sword of our devout and necessary technology- and screen-mediated relationships.

Sicheng Wang’s lovely, iterative paintings of Baltimore sunsets—two to a page, the pages taped in an orderly grid to a movable wall—elicit obsessive attempts to understand a new place, focusing on a simple, reliable, even comforting constant: No matter where you are, the sun falls each evening, coating the same buildings and surfaces with a golden, rosy glow. (Rebekah Kirkman)

Woven Words: Decoding the Silk Book, through April 28

Walters Art Museum, 600 N. Charles St., Baltimore, 21201

Hours: Wednesday–Sunday 10 a.m.–5 p.m. (Thursdays open till 9 p.m.)

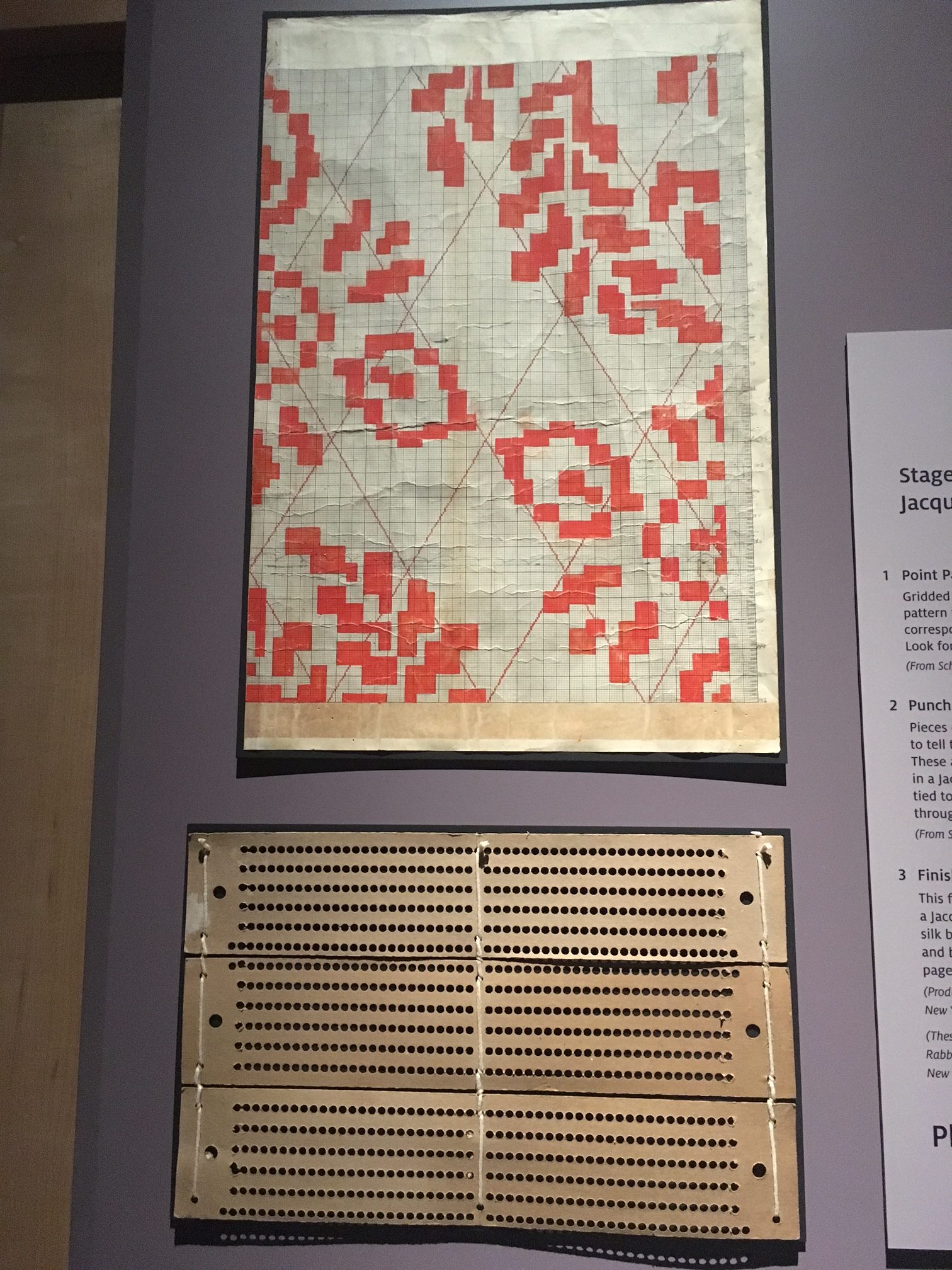

The object this exhibit tries to decode is a small prayer book whose 43 highly decorated and illustrated pages were fabricated entirely of silk threads woven together on a Jacquard loom in 1886. The Jacquard loom, considered a progenitor to the computer and its binary language of zeros and ones, operates with a system of cards punched with holes that press against rods that control which warp threads are raised in order to allow the weft threads to pass through, creating the pattern. A short video illustrates this, though I have to admit that it all still feels like math class to me.

Also on display are student manuals from the same time period and location (Lyon, France) when the silk book was made; the manuals contain diagrams, designs, notes, and weaving samples, offering a window into the process. One book is opened to a page that shows how to weave a lily pattern, beginning with the colorful design laid out on point paper (which would then be translated into hole-punched cardboard which would be fed in the proper order into the loom mechanism), along with a sample of the final product.

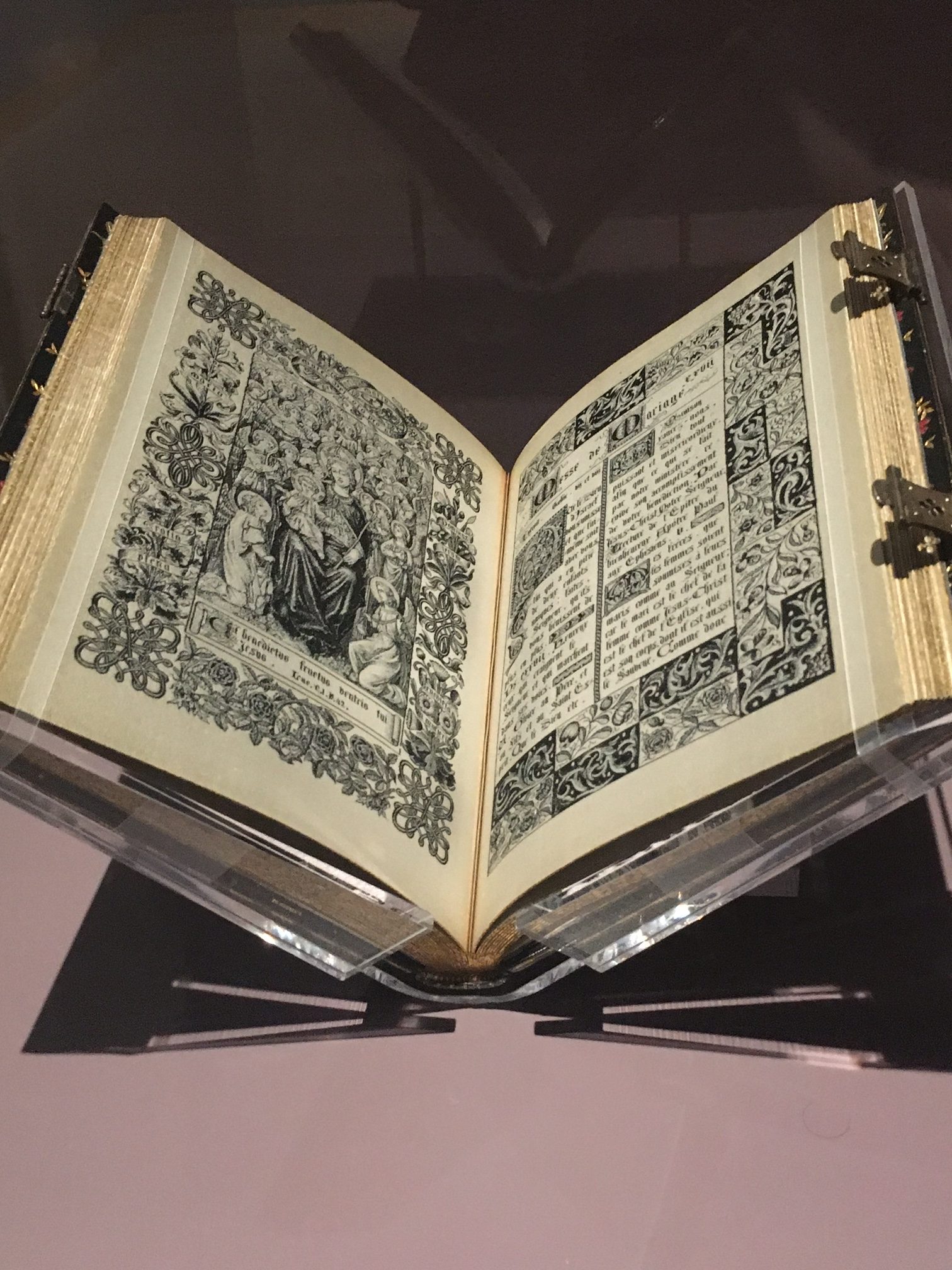

This lily sample is rather large in comparison to the florals in the prayer book, which are obscenely tiny and intricate. You can flip through a digitized version of the book on a tablet in the gallery, and the actual book is displayed under a case, open to what might be its most mind-bendingly intricate spread; the left page featuring a border of complex, shaded knots, foliage, and flowers around an image of the Virgin Mary surrounded by angels, also highly detailed and shaded, the right page displaying a marriage prayer in a gothic font, the text surrounded by varying floral tiles whose backgrounds alternate in black and white.

It is astounding that this silk book was made at all—an ordinary object transformed with a 19th-century flex of excellence in skill, craft, and design–but was it ever even used? It was made for the 1889 World’s Fair, an event whose main purpose was for countries to show off their homegrown innovation. And although you don’t have to have a math mind to appreciate the labor that went into this rare book’s creation, I assume it helps considerably. (RK)

“Return of the Garden” by Sharon Servilio

“Return of the Garden” by Sharon Servilio

Temporal Embodiments: Sharon Servilio and Sylvia van Helden through April 28

Julio Art Gallery, Loyola University, 4501 N Charles St, Baltimore, MD 21210

Weekend Hours: 1 p.m.- 4 p.m. on Saturday and Sunday

Tucked in between Loyola University’s lacrosse fields and English Tudor buildings, the Julio Gallery is a beautiful little space with sweeping high ceilings, natural light, and blonde wooden floors. It’s current exhibit, Temporal Embodiments, features small and medium-sized collages by Baltimore-based Sylvie van Helden and New York-based Sharon Servilio; it’s a well appointed show with the right amount of white space and a visual synergy between artists through color choice and a blithe, modern spirituality. I’m not sure if the exhibition title, Temporal Embodiments, is intended ironically or in earnest, but it suggests a type of mystical experience that is vaguely inspiring and suggestive of self-care and wellness and yoga and accompanying Instagram hashtags. I’m not complaining about this, but it is worth noting because it’s a sticky slope, chasing after the sublime using elements and vocabulary from popular culture.

Sylvie van Helden’s mandala compositions in varying color schemes are constructed from images she finds through Instagram searches, connecting a symbol of ancient spiritual power to our collective addiction to shallow online image curation. Again, I wonder if this is earnest or the artist is messing with us, because the collages are so pristine and perfectly executed. Most of them are covered in a slick and delicious coat of resin, rendering them jewel-like and purposeful, with each radial composition floating just below the shiny surface. The physical depth in van Helden’s surfaces coupled with their intricacy reinforces their spirituality and seriousness, but closer inspection reveals human figures and logos coupled with Buddha heads and abstracted plant forms and they hum with a weird humor that makes their vision of divinity complex, modern, and curious.

Servilio’s compositions are blockier and more cartoon-like, shallow relief sculptures of folded paper and other hand-cut shapes wedged together into shallow wooden box frames. They are painterly and also cartoon-like; they flatten out into neat compositions in photos, but in person are bursting with odd additive elements and structures that communicate a sense of wonder coupled with a goofy humor. In “Return of the Garden” 2018, lush green plants ravish an open laptop struggling ineffectively against nature, with a giant Monarch butterfly wing and tiny computer icons battling for control. I’m not sure if this is an artist fantasy or a dire prediction of our inevitable future, but it’s so juicy and brimming with a “Nothing But Flowers” insouciance that I feel ready for the apocalypse.

Can humans be serious about spirituality and make fun of it (and themselves) at the same time? Servilio and van Helden make the case that both devotion and silliness are essential in feeling a divine connection. (Cara Ober)

Images of Crossover and Woven Words by Rebekah Kirkman

Images from Temporal Embodiments by Cara Ober