“People aren’t thinking, they’re waving flags,” said artist Elizabeth Catlett in an interview, worrying about the state of America and its rush towards fascism. It’s unclear when the interview was recorded, though it was posted to YouTube in 2010, and I would guess it took place in the early 2000s given a few context clues, including that era’s particular rise in blind patriotism. The statement’s specific context, though, matters less than its content: Catlett’s observation is one of those timeless truths; it obviously rings true today, but she could have also said it while growing up in segregated Washington, DC, or in 1962, becoming a Mexican citizen and relinquishing her US citizenship when it listed her as an “undesirable alien” because of her leftist politics. Though she had regained her US citizenship in 2002, she lived in Cuernavaca, Mexico, until her death in 2012.

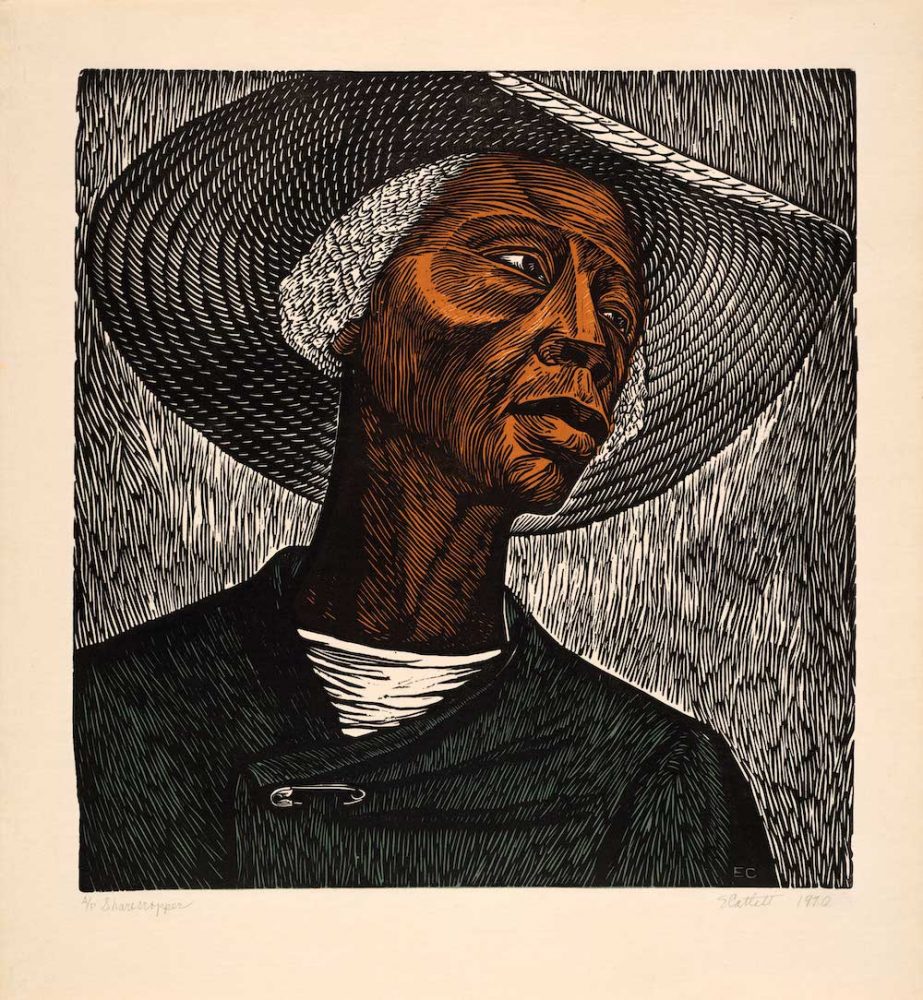

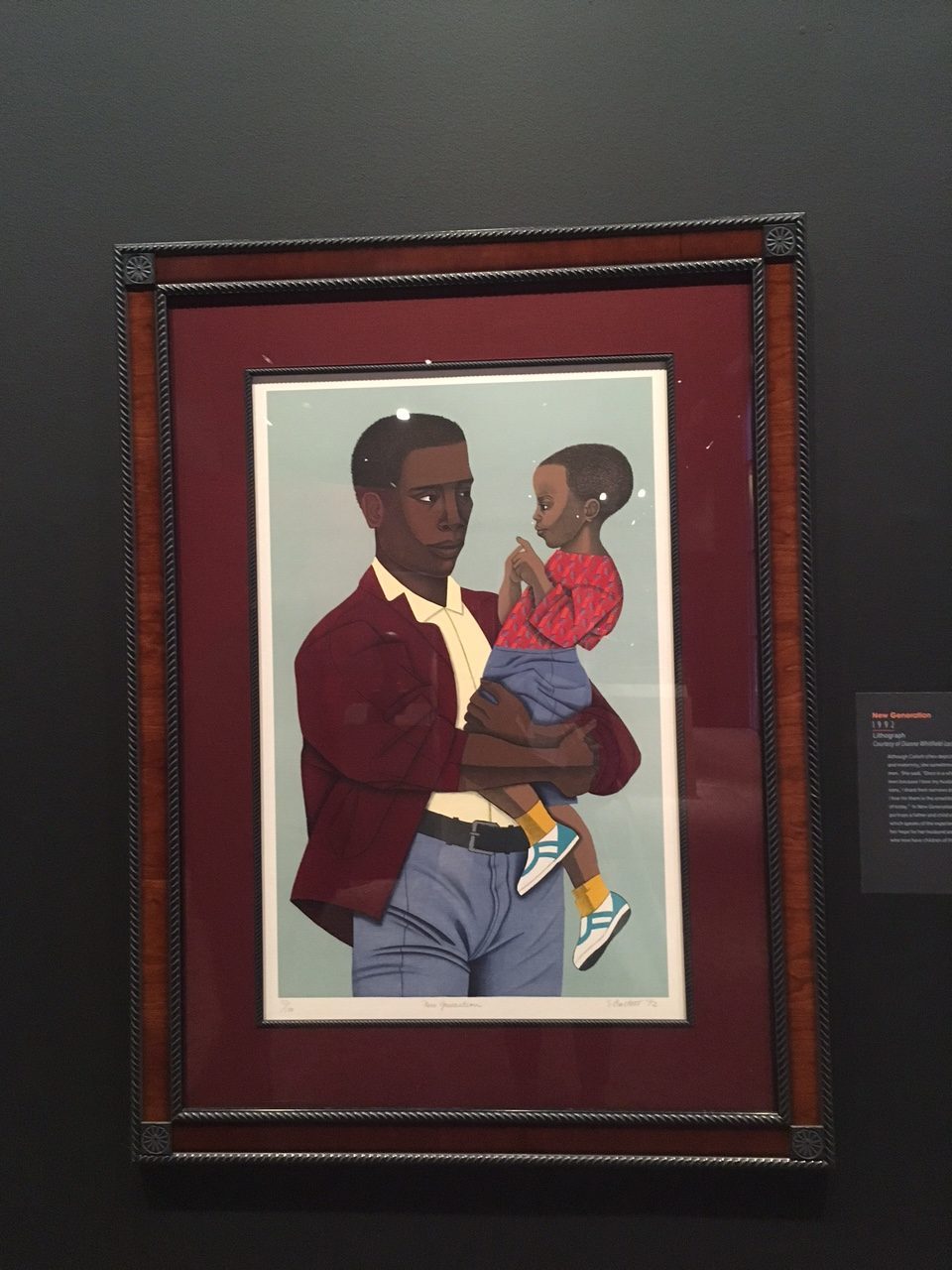

Throughout her career, Catlett’s work was consistently just as prescient—and present with her own time and place—as that statement. After moving to Mexico City on a fellowship in the 1940s, she got involved with a print workshop where her activism was tied to her work—she demonstrated with fellow artists, printing signs and pamphlets supporting union workers on strike. Her prints and sculptures uplifted the worker: Field workers, sharecroppers, mothers, grandmothers (and occasionally fathers too) share space in her oeuvre with abolitionists and civil rights icons, everyone with dirt under their fingernails, everyone in all of their ordinary glory.

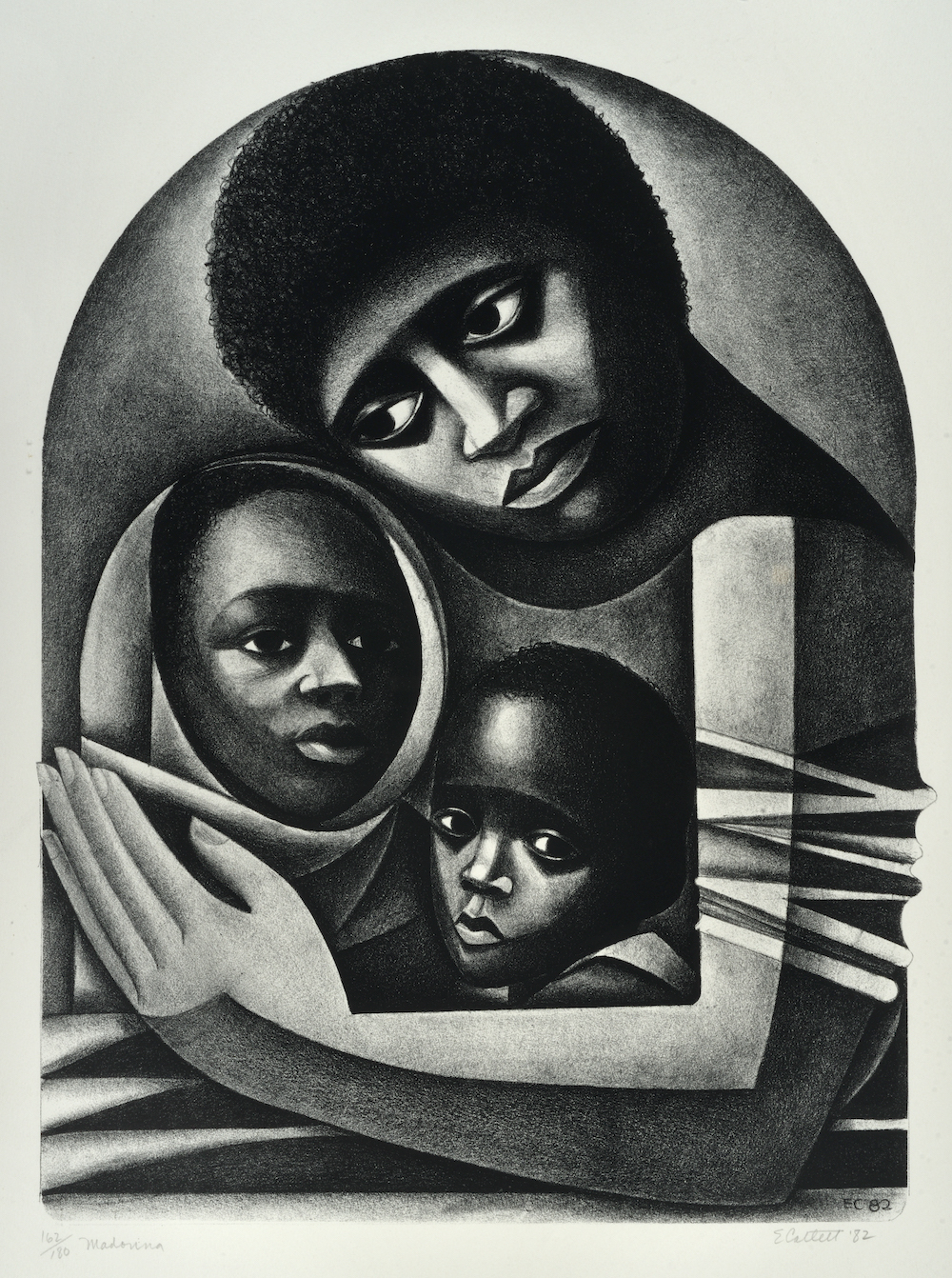

The Reginald F. Lewis Museum’s dynamic exhibition Elizabeth Catlett: Artist as Activist, curated by museum director Jackie Copeland, tracks the artist’s career and her recurrent themes of the valorized worker and the industrious woman. The exhibition is bookended by portraits signifying laborers in the US and Mexico—and at its center, women, children, and mothers recur as frequent subjects, along with a few recognizable abolitionists and icons. This structure suggests a motivation for wide-ranging solidarity; here there’s no distinction between the labor of raising a family, field work, and movement work.