How does your identity, however you want to describe that, inform or affect your artistic practice?

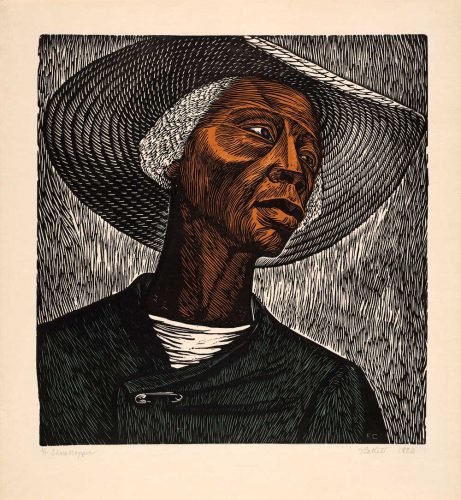

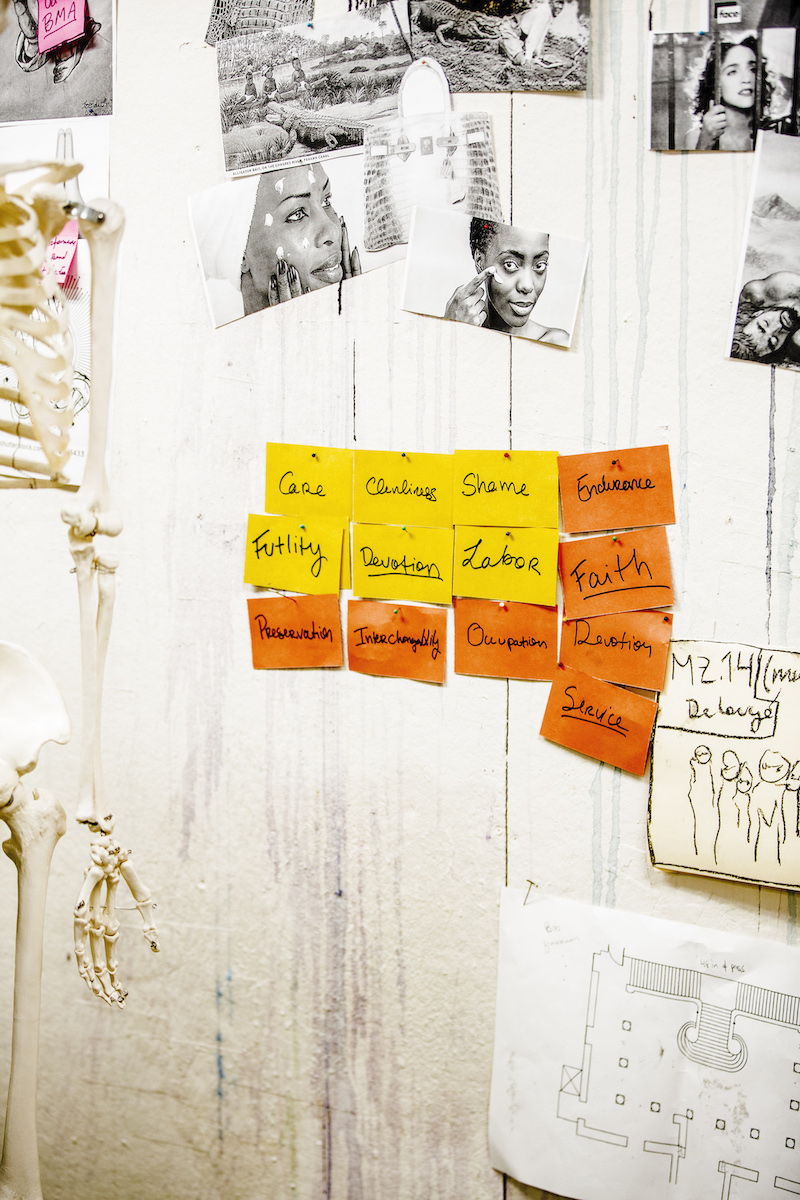

Being a queer man of color is in and of my practice. I think it’s my relationship to humor and sadness and being able to like understand those two ideas, my relationship with my Blackness and Frenchness, my Africanness, is truly the material that I started to build my practice off of. Sometimes I wonder what would happen if I was one less thing, or one more? I think everything would look different. Truly, my main medium is my history. I think a lot about my identity. I think a lot about acts of labor. I think about who’s working and what work they are doing. I think a lot about privilege and who has it and what it is. I think about it from a lot of different perspectives.

If you had to give one distinct piece of advice to yourself when you were applying to your program, what would it be?

“Good job, girl. Truly good job. And, you know, finish that application.”

What major decision have you made recently that has impacted your work and life?

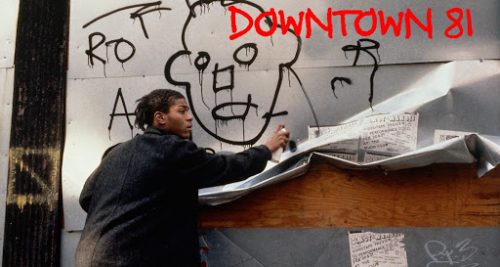

Leaving New York was one of the biggest and scariest decisions I ever made because of this idea that you’re taught there, that you work all the time to make your work, and then you work some more. In New York, you have to stay there and grind without stopping until something happens. And I think this is a hoax manufactured by the city of New York to keep you paying the high rent. I realized that a lot of my friends didn’t live in New York anymore. And while everyone else was off doing their work, paying the rent, and going to parties, I was done there.

What place in Baltimore inspires you the most?

The Crown on Tuesdays at 9 p.m.! Karaoke Forever is a place where I really found my voice. I’ve always performed; I’ve always performed live. I’ve always sang live in my performance work, but I’ve always had a fear of microphones and the amplification of my voice. It is terrifying and disorienting. Being able to go there every Tuesday and, just in general, the idea that I can go perform karaoke every night is powerful. I perform somewhere every night in Baltimore. It’s been such an enormous help. Also the fact that I can get feedback from an audience keeps the work moving.

Where do you get the materials that you use in your work from? How do you pay for them?

I’m attracted to domestic materials. I am attracted to the symbols. I’m also attracted to objects that you could just straight buy from the art supply store, but usually life happens in a Costco or or Kmart or Target. I like consumables, things that people already have access to, and I like watching myself reinterpret them or explore them. I’m attracted to objects that have an intended sense of labor and I’m interested in excusing them from that task.

Sometimes I find that art—art making, art craft—those materials can be a little too elitist for me. I never really liked the idea of oil paint because—why would I waste my time? It’s a time suck, you know? And it’s expensive. Especially when I can find more meaning in household materials. My mother is a caterer and event planner and I always found my lexicon in her practice, and I always told myself that if my mother doesn’t have it in house, I can’t use it. So I work with canvas, fabric, paper towels, cotton balls, and diapers and [looks around studio] Windex and fake flowers, and find purpose in the repurposing.

You have an eye for fashion and you briefly mentioned that you have a fashion background. I know that your practice weaves in fashion, but why don’t you just straight up become a designer?

I still might be, girl. I feel like I can’t stop myself like that. When I was an undergraduate, there was a very big conversation about my relationship to practices outside of fine art making. I got to New York and they were like, if you want to go do fashion, girl, go over there. Here is an application to FIT—literally one of my teachers gave me an application to FIT. And what does that say? I smiled and said thank you. And I kept pushing it, and then I started making performance art. I just doubled down on it because I can’t simply be a fan. I still have ideas for clothes. I still have intentions to make clothes.

Has anything about being a student at this institution disappointed you?

I have had a hard time finding time within my program to enact my performances due to the sheer fact of there’s a lot of students… and the more time I take away to have people view me takes time away from another student. So if I did a 10-minute piece that’s really a lot, and then I would still need my 30 minutes of critique afterwards. I was disappointed about that at the beginning, but I’m no stranger to time constraints. I present performances that I can do in a short amount of time. I have also found that working outside of the institution and using Baltimore as my venue solves the problem.

That’s something that I find endearing and dynamic, your relationship with this city.

Baltimore is a place where, if I am not getting what I need from the program, I can get it somewhere else. I don’t know if I went to school anywhere else that would’ve happened…

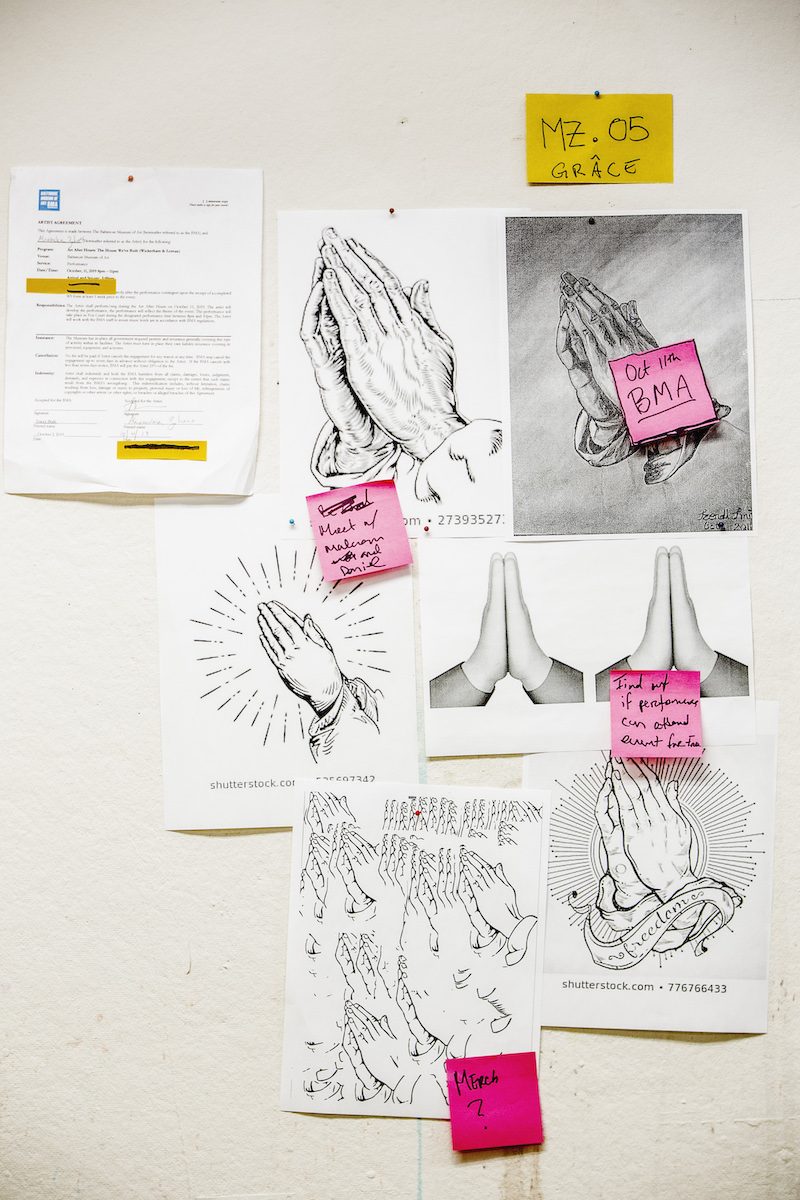

What are you working on right now?

I’m working on my thesis. It’s a massive, three-part spectacle that is going to be taking place in the Main Building at MICA. Keep April 20th open. I have a whole building to myself and I will be presenting the girls my thoughts on the last two years.

What are your post-graduation plans?

I’m not sure just yet. Baltimore has been so welcoming and gracious to me that part of me wants to stay. But part of me wants to keep moving and see where else my journey can take me. But if anyone reading this has any ideas, I am open to hearing them.

**********

The purpose of MASTERS is to highlight artists who are studying in graduate programs in the Baltimore area, and to allow other creatives the opportunity to see what it is like to be a graduate student in the arts.