Ebony and Jet are leaving Chicago. Last summer, four foundations—Ford, Mellon, MacArthur, and the J. Paul Getty Trust—purchased the Johnson Publishing Company’s photo archives for $30 million. The collection will be housed between the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC and the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles, eventually to be made publicly available. I couldn’t help feeling a little chagrined thinking about this final chapter of the once indomitable publishing house. First their iconic downtown Chicago headquarters was sold and turned into apartments. They sold their publications in 2016. And now, the photo archives—four million images and negatives depicting Black life through a Black lens. Couldn’t they have held onto and managed their own history?

My fantasy of a Johnson Publishing Company-run archive has everything to do with what they represented: a glamorous Black business that created and interpreted Black visual culture for the benefit of Black people. That’s powerful. This loss hits close to home. My family has owned and operated Baltimore’s AFRO American Newspapers since 1892, and has maintained its archive for as many years. We have been a beacon for historians looking for written resources from Black perspectives throughout the past century, but the visual culture documented in our archive has yet to be explored in great depth. What new connections might emerge by inviting thinkers and makers with diverse educational backgrounds and practices into the archives? How can we expand notions of scholarship, and facilitate an intimacy with history generated by and for Black people?

In her 2018 article “Archiving While Black,” historian Ashley Farmer points out that archives at predominantly white institutions have never been welcoming to people of color. She shares an anecdote from revered African American historian John Hope Franklin about his attempt to conduct research in an archive in North Carolina during the Jim Crow era. He was told he would have to wait several days while one of the exhibition rooms was converted into a segregated reading room for him. Farmer goes on to describe contemporary instances of exclusion and discomfort when working in white institutions, but the Franklin story swiftly gets to the point: The exclusion of Black researchers is embedded into the literal structures of white institutions.

While there are formidable Black archives available throughout the US, scholars of Black history still have to navigate collections created and compiled by white institutions. The information found in these collections can be useful, but often suffers from bias-informed omissions, misrepresentations, and evidence of willful misinformation. To arrive at an understanding of Black subjectivity through these source materials, an additional layer of contextualization and translation is required.

Saidiya Hartman, an African American literature and history professor at Columbia University and a 2019 MacArthur fellow, focuses on the lives of city-dwelling Black women in the early 20th century in her book Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments. To unearth their stories, she had to reckon with archives that represent these women as nuisances. Hartman read between the lines of trial transcripts, slum photographs, and rent collectors’ journals to detail these women’s experiments with freedom, only two generations after the end of slavery. In Hartman’s reading, Black women who took multiple lovers are depicted as self-possessed, rather than immoral, as they indulged in newfound authority over their bodies and desires. Those arrested for “vagrancy” become modern citizens trying on the concept of leisure. Her scholarship complicates history, reframing Black women who necessarily lived outside of dominant social norms as innovators pushing against the contrived limits of a society that never understood them.

To arrive at an understanding of Black subjectivity through these source materials [compiled by white institutions], an additional layer of contextualization and translation is required.

Since Fred Wilson’s 1992 Contemporary Museum show Mining the Museum, at the Maryland Historical Society, more institutions have been inviting artists to take on the role of researcher/troublemaker. Wilson unearthed objects the MdHS forgot they had or didn’t know what to do with—a KKK hood, slave shackles, Benjamin Banneker’s journal—and positioned them in charged arrangements, posing questions not only about what was missing from these collections, but how meaning is made through what gets displayed publicly. For institutions that interpret their own collections for the public, how they present these objects can say as much about their values as what’s in the collection to begin with.

Artist Kiyan Williams pushes this tension in their work with filmmaker Marlon Riggs’s collection in the Stanford University Libraries. Williams came across an unedited interview with Jesse Harris, a gender non-conforming artist and poet who, in the midst of an interview with Riggs, is harassed by a group of people in the park. Harris responds, defending themself, and then returns to the interview. However, in the released version of Riggs’s seminal 1989 documentary film, Tongues Untied, Jesse’s voice is silenced, the harassment and self-defense are edited out, and instead, we get a shot of Harris from a distance, with a Bessie Smith song overlaid. Using the archive, Williams reintroduces Jesse’s words to the public through performance and performative lectures given at venues across the country, reinserting Jesse’s poetry and resilience into the discussion of queer life in the late 1980s in New York City.

In the summer of 2019, I returned to Baltimore to work within the AFRO’s massive and often overwhelming archive. As I consider how to make it more accessible to the public, I’m reflecting on the generations of labor and vision that got us to this point, 127 years later, and thinking through the inherent tensions between access and conservation, personal and public histories, the power of the publication and archives being privately Black-owned and -operated, and the material challenges associated with keeping them as such.

As I’m thinking, I’m also experimenting. In the spring of 2020, a Grit Fund grant will support an exhibition with three contemporary artists making new work inspired by the AFRO’s archives. This project is a pilot that will ideally lead to more artistic engagements with the collection. We hope to open up new dialogues about Baltimore’s history and its inextricable tie to the present in an effort to collectively reimagine the future.

Beyond physical interactions with the collections, I am also inspired by the ways artists and culture makers are using social media to combine their own research with content provided by their followers, re-presenting imagery within their own curatorial frameworks. Webster Phillips’s I. Henry Photo Project (@ihenryphotoproject), Lawrence Burney’s Laurels History (@laurelshistory), Renata Cherlise’s Blvck Vrchives (@blvckvrchives), and Guadalupe Rosales’s Veteranas and Rucas (@veteranas_and_rucas) and Map Pointz (@map_pointz) come to mind as beautiful new models for sharing and interpreting overlooked histories in the digital landscape.

While there will always be a certain magic in the intimate act of holding a piece of history in your hand, that experience doesn’t have to be a rarified one. We’re all making history every day. The documents we hold onto and the files we save are the archives of the future. What will you keep?

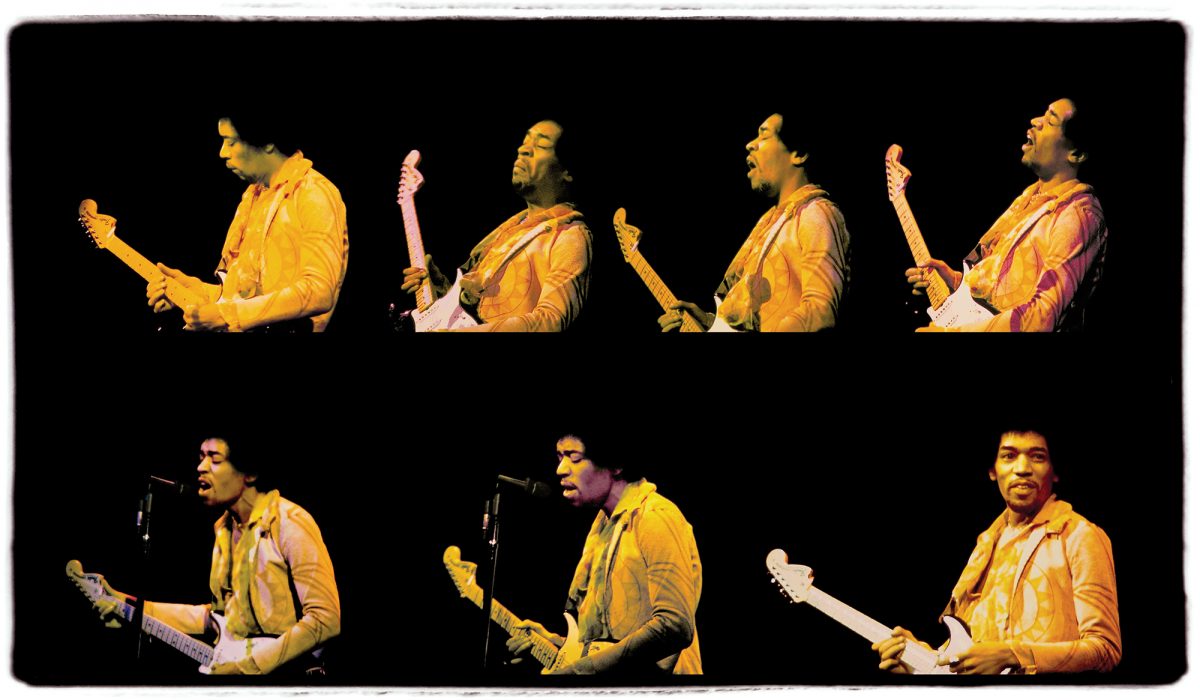

Image courtesy of The AFRO American Newspaper Archives

This story appeared in BmoreArt Journal of Art + Ideas Issue 08: Archive.

Savannah Wood is an artist and cultural organizer with deep roots in Baltimore and Los Angeles. Through her work with LA-based arts organization Clockshop, and Theaster Gates Studio in Chicago, Savannah has had the opportunity to work with incredible archives, interpreting their contents for the wider public. She has recently relocated to Baltimore to create programming and infrastructure that will increase access to the Afro-American Newspapers’ extensive archives. This work is supported in part by a Robert W. Deutsch Foundation Fellowship. Savannah is interested in uncovering obscured histories, tapping into ancestral magic, and forever learning more about human nature. She makes photographs, clothing and plant-based sculpture.