This essay was composed in April 2020.

Living with art during stay-at-home orders has changed my relationship to the images around me. The prints, paintings, photographs, and sculptures seem different, endowed with new resonance—some tender or morose, some aggressive or accusatory. Since I am not currently co-habitating with anyone, this is what I notice. There are no restless children, no agitated roommates, no quarrels with lovers. There is a great deal of silence, solitude, and gazing at the walls. Now the textures of the art I have collected are more real, more tangible, than the textures of human faces. At night, I sometimes feel as though my apartment is floating in outer space. The world—at least the one in which I physically reside—has closed in on itself, tightly reframed.

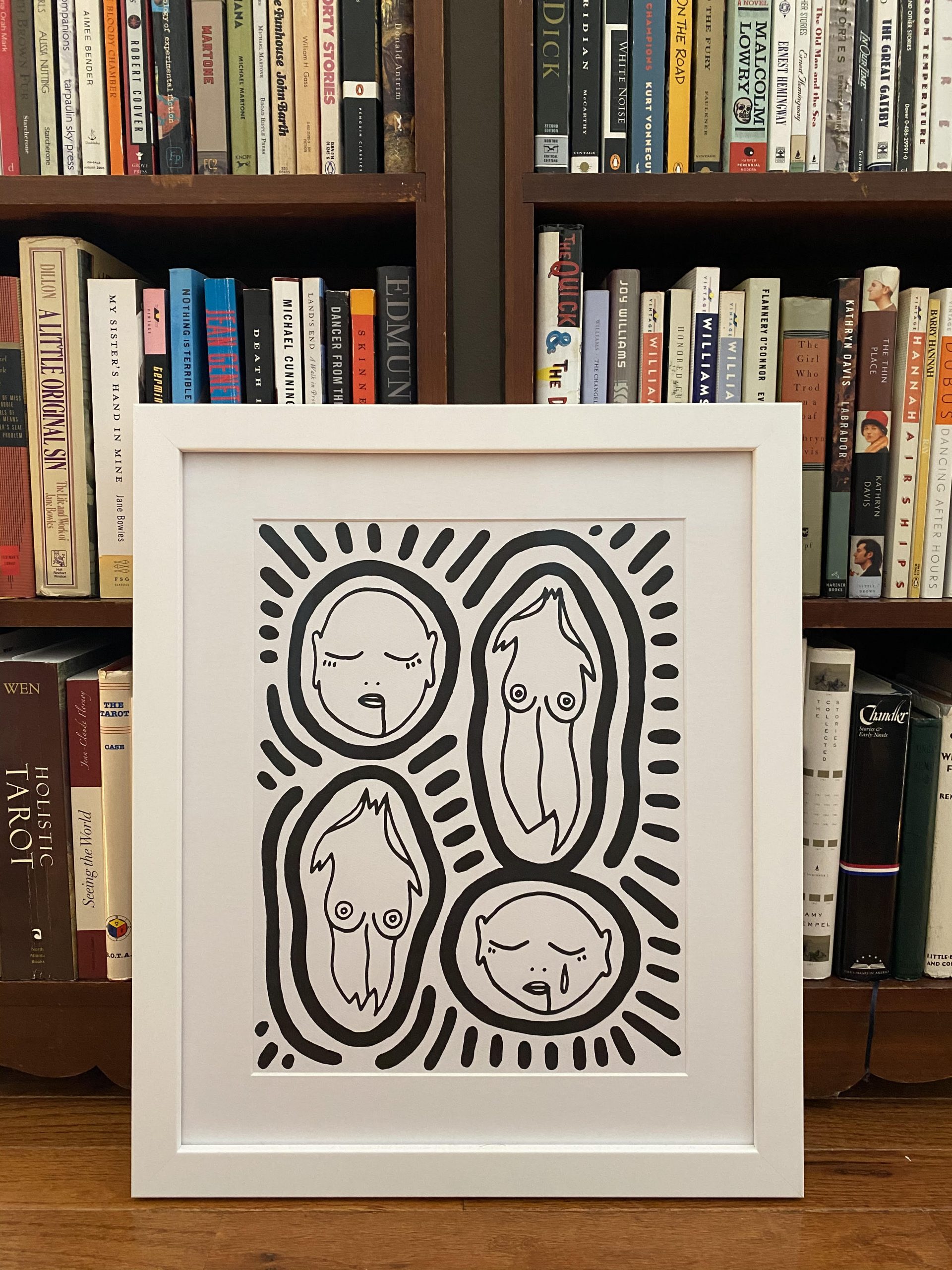

I find myself frequently staring at a print from Patrick Church’s All Over You series. Composed of relatively simple lines, All Over You depicts disembodied heads and torsos, separate and suspended, floating around like amoebae. Thick lines encase, curve around or, more often, radiate from these enclosed bodies as if each had a magnetic charge rendered in cartoon form. Though in Church’s world, bodies are much more likely to remain isolated than to touch.

Since mid-March, we’ve been profoundly disconnected from one other, at least physically. We make phone calls and text and video chat, but the ways we used to connect are still very remote. We are making do—an act of creation born out of necessity. We have been creative, but we are also biding time till our connections are restored.

The melancholy faces in All Over You are assembled in a loose pattern. All the eyes are shut. Some faces have one tear, some two tears. Some of the mouths have let run a rivulet of saliva, the aftermath of serious sobbing, a suffering that reads as both genuine and theatrical. There is a quality of Church’s work that is capital-R Romantic, pure-hearted and idealistic. The academic brain might critique this sentimentality, yet the emotional body may more readily understand—and welcome—the simple truth of sorrow and loneliness.

My print of Church’s All Over You is framed, but currently leans against the wall awaiting placement. Because the print isn’t yet hung, and because I have rearranged my living room several times since the beginning of social distancing to better accommodate floor exercises, All Over You keeps moving.

Grief is knowing you’ve lost something valuable and feeling unsure that something of equal significance will fill the chasm.

There is nothing easy about staying at home when the people and places you rely on for solace, safety, reassurance, intellectual engagement, and stability are off-limits. As with any severing, the separation feels violent. The severed torsos in All Over You have ragged edges where the arms, pelvis, and neck should connect. These limbs are not neatly knocked off like some Greek sculpture. The dismemberment indicates a myriad of suffering: no cerebral faculties, no means to have sex, no ability to tend or to touch. Movement is rendered an impossibility, yet the core of the body remains.

Church created this motif when he first moved from London to New York City with his husband. While his husband was at work, Church felt tremendous isolation despite the fact that he could be surrounded by people the moment he opened his door. I’ve moved often, with no husband, and I know how hungry one can be for something more than casual interaction. But I also know that simple exchanges can offer a reprieve from all the chatter in one’s own mind. Glimpsing others living their lives in the same city with relative ease can bring momentary solace. Look how easily one might walk down the street, fresh air on the face, trees green and filtering the sunlight. Look how easily one might smile at a neighbor and feel friendly.

I worry that others might view Church’s work as saccharine or cloying. But grief is a syrupy emotion; grief has a tendency to stick around even when it’s not particularly nourishing. Grief is crying into a bowl of Lucky Charms in your empty apartment in a foreign country. Grief is knowing you’ve lost something valuable and feeling unsure that something of equal significance will fill the chasm.

Social distancing requires that one grieve in relative solitude. No congregations, no assemblies, no vigils. The only one watching, vigilant, is you.

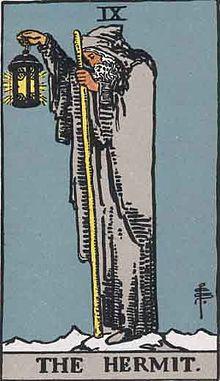

In the Tarot, Pamela Colman Smith depicted The Hermit as a white-bearded man holding a staff and a lantern on a snow-capped mountain peak. Although “hermit” evokes solitude, there is also a religious connotation to the word, and therefore a degree of voluntary action. The hermit is not one who is forced to be isolated, but rather one who is isolating in response to a calling. His label is not about punishment or exile, but one of vocation. This archetype resonates with how we are meant to be isolating now—not for our own sake but for the sake of something greater. But serving something greater doesn’t nullify the sacrifice of what one leaves behind, of who one leaves alone.

One of the most difficult aspects of the first week of social distancing was that I was no longer able to take care of people (or be taken care of) in the ways I know best. I could no longer walk into a classroom and feel the energetic pulse of my students; I could no longer shake up cocktails to share with friends in my living room; I could no longer hug or be hugged, hold or be held. Even as one who loves boundaries, navigating these sudden barriers seemed insurmountable.

I wonder if there are really only two responses when presented with a problem: to figure something out or to resign oneself. The faces in All Over You appear resigned, defeated. But as the viewer of the painting, one can choose to figure something out about the pattern, to assemble a more nuanced understanding. There are slight variations of face and torso, and subtleties in the arrangement of curve and line. The title can be read two ways: All Over You, as in obsession, all-consuming desire, unbridled craving; or All Over You, as in the soon-to-be-forgotten, moving you to the past out of necessity, getting over it. As in, I’m moving on.

When I visited the Acropolis last year, I witnessed restorationists trying to figure something out. Weather and war have worn away the site and this restoration effort has been underway to make sense of—to sort, arrange, and reassemble—the rubble since 1975. There were assorted columns on the ground, like sticks of chalk, neatly lined up and waiting to be used. As I stood on that peak above Athens, I knew: Placed in charge of that rubble, I would resign the mess to remain a mess. I knew that I would grieve the immense loss but also lack the drive to reconstitute a thing so monumental. The scope of the project, from my view, is impossibly large. Instead, I stood in front of the Parthenon in my combat boots and held up a victory hand while a friend took a photo. My impulse was to feign victory atop a feeling of defeat—and then to move on. The impulse of the restorationist is resilient perseverance, the all-consuming desire to build again.

To be a hermit is to both stand in solitude and symbolize unification. To be a hermit in a pandemic is a paradox. In a world full of newly minted hermits, hermits are alone in this together.

Church has refashioned, reconstructed, and rebuilt his All Over You motif on countless objects: leather jackets, denim, a gold-chained thong, pajama sets, fanny packs, the sofa and the piano in his studio, Louis Vuitton luggage. All Over You is all over everything, making loneliness a persistent, universal language.

At night, I stare at my little rectangle of Church’s All Over You, knowing that others, somewhere, are also sheltering in place with this motif in their homes. There are not enough lamps in my living room, so the light is dim. I think again of the Hermit, alone atop the mountain, holding a lantern that contains a star, the sole light in an otherwise-starless night. Yet the occultist Paul Foster Case wrote of the Hermit: “the light of a golden, six-rayed star, and its interlaced triangles are symbols of union.” To be a hermit, then, is to both stand in solitude and symbolize unification. To be a hermit in a pandemic is a paradox. In a world full of newly minted hermits, hermits are alone in this together. Imagine them, looking from their respective peaks toward one another, a nod across the valleys. Look to your neighbor’s apartment window, also glowing in the middle of the night.

There is pleasure in recognition. Three times a week, familiar faces assemble in my Zoom “classroom” and provide some semblance of normalcy, though I acknowledge that none of this is normal. I am attempting to teach the lyric essay—a genre that is difficult, as there is no concrete definition, there are no steadfast rules, and we humans tend to struggle with ambiguity. But precisely because of this ambiguity, the lyric essay also feels well-suited to “these uncertain times.” No one has all the answers, and that uncertainty is the common human condition from which all good essay writing begins. Through fragments of narrative and analysis, the writer watches for what accumulates and looks for patterns to emerge that might yield some understanding. My students prove remarkably adaptable, game to puzzle through their own lives.

In an interview with NPR’s David Greene, American astronaut Jessica Meir reports from the International Space Station that she often listens to Greene’s show and that hearing a familiar voice speaking to her in space is wonderful. After seven months in the most foreign of territories, Meir thrills at the familiar. Meir knows that she will be quarantined upon her return to Earth, as astronauts may be immunocompromised after a mission and she will be returning to a planet with a pandemic. She expects that challenge of isolation on Earth to be more difficult than living on the International Space Station, as she has had years of training for the latter. While drifting above the southeastern corner of Australia, Meir tells Green: “I think it’s going to feel a whole lot more isolating down there than up here.”

Church feels isolated well before the pandemic, lonely in a galaxy of people—in New York City, of all places. The faces and torsos in All Over You form constellations. Though self-contained, they also radiate. The loneliness of the individual is communal, transmitted, understood. The mouths of Church’s faces are all full-lipped but closed. Loneliness so often breeds silence.

I am typically not one to live in silence. I have synchronized speakers in every room of my apartment for music or podcasts. While reading a book, writing an essay, cutting up vegetables, or wiping down surfaces, I seek out sound to accompany me. But since the coronavirus began to spread, I have found myself letting the silence settle. Letting the songs on the playlists run out. This more extreme stillness has become, at times, preferable—and I don’t know why. When I receive texts that ask how I am doing, what I am doing, I am sometimes just sitting. Sometimes pacing. I wander in orbits around my apartment at night, the silence deafening as space, till the light rail rushes by, bright like a familiar comet.

Robin Givhan of the Washington Post writes that silence during Covid-19 is “a voracious monster that has snuffed out the reassuring rumble and roar of daily life,” though I’d prefer not to think that I am snuffing out my own reassurance by choosing not to press play. Certainly there are fewer voices in the rooms of my apartment, but this is not the type of silence Givhan is writing about; she is mourning the din of a vibrant city, the sounds that convey a collective vitality. The rush of the morning commute, school yards, sports in the park, strolling shoppers, restaurants with outdoor seating. “Still,” writes Givhan, “one wonders whether the discomfort with silence is exacerbated by solitude. Or can silence cause loneliness? Perhaps the brewing uneasiness is just the desire to hear someone say: You are loved. You are valued.” Even astronauts have a crew; even Church has a husband.

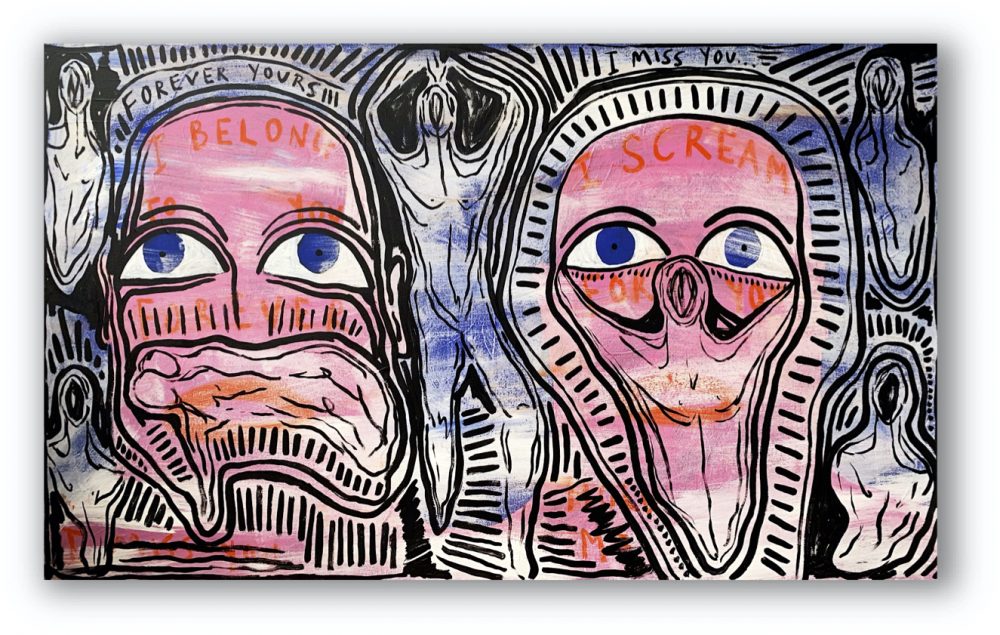

In 2019, Church’s solo exhibition, A Hell of My Own Making, opened in NYC. In a departure from the All Over You series, Church populated his canvases with lithe, faceless figures reminiscent of William Blake’s visionary paintings. Compositionally, Church’s new work is strikingly different from the old—though literally built on its foundation. The new work is painted directly on top of the previous work, laying bare the process of each painting’s evolution. A standout piece, titled Eternity, focuses on two rose-pink faces, eyes wide open and lapis lazuli blue. One face confesses the words “Forever yours, I belong to you forever”; the other face, “I miss you, I scream for you.” Just as in All Over You, there are two sides to this intimacy: a bond that reveals a separation, a separation that reveals a bond. There are also barriers here, as the mouths and noses of the two faces are covered with other figures, wearing these bodies like masks. Bodies are the fear and bodies are the desire. As is so often the case, what we fear and what we desire reveal themselves to be the same. Though I couldn’t discern the words till I was up close in person, at the bottom of Eternity, Church painted the words: hold me.