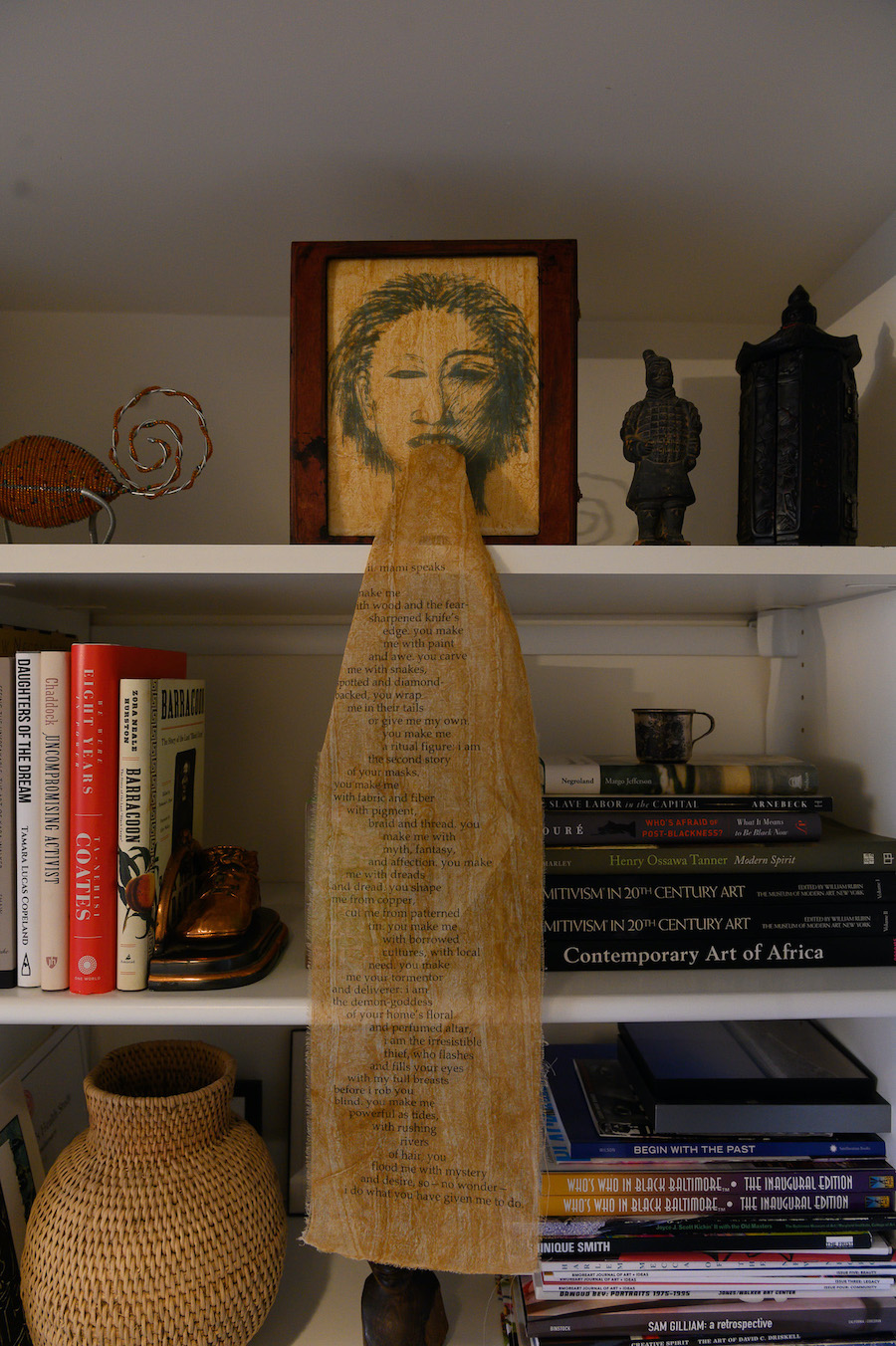

The first piece of art Jackie Copeland ever bought is mounted on a wall right next to her desk in the second-floor study of her Pikesville home. It’s a wooden plank mask from the Mossi people of West Africa that Copeland, the former executive director of the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African-American History and Culture, bought when she lived in Chicago in 1975.

On her desk is a Lorna Simpson mixed-media piece featuring a small, felt-lined wooden box that contains ceramic, rubber, and bronze wishbones. The shelves above her desk house rows of books ranging from contemporary art and photography to history, biographies, and artist books. A few frames sit in a row on the floor, waiting for open wall space: a Roy DeCarava print, an early painting by Shinique Smith, a work by the late David Driskell.

Opposite her desk is a compact sofa, on which sits a pillow whose cover features a textile rendering of a Black woman in soft pink holding an expansive bouquet. “A friend of mine gave this to me,” says Copeland, reaching for the pillow. “It’s from Manet’s Olympia. It’s the maid that is handing her the flowers.” She points out other items in her collection—Black memorabilia, daguerreotypes. “This is my little area here, a collector’s study. I love it.”