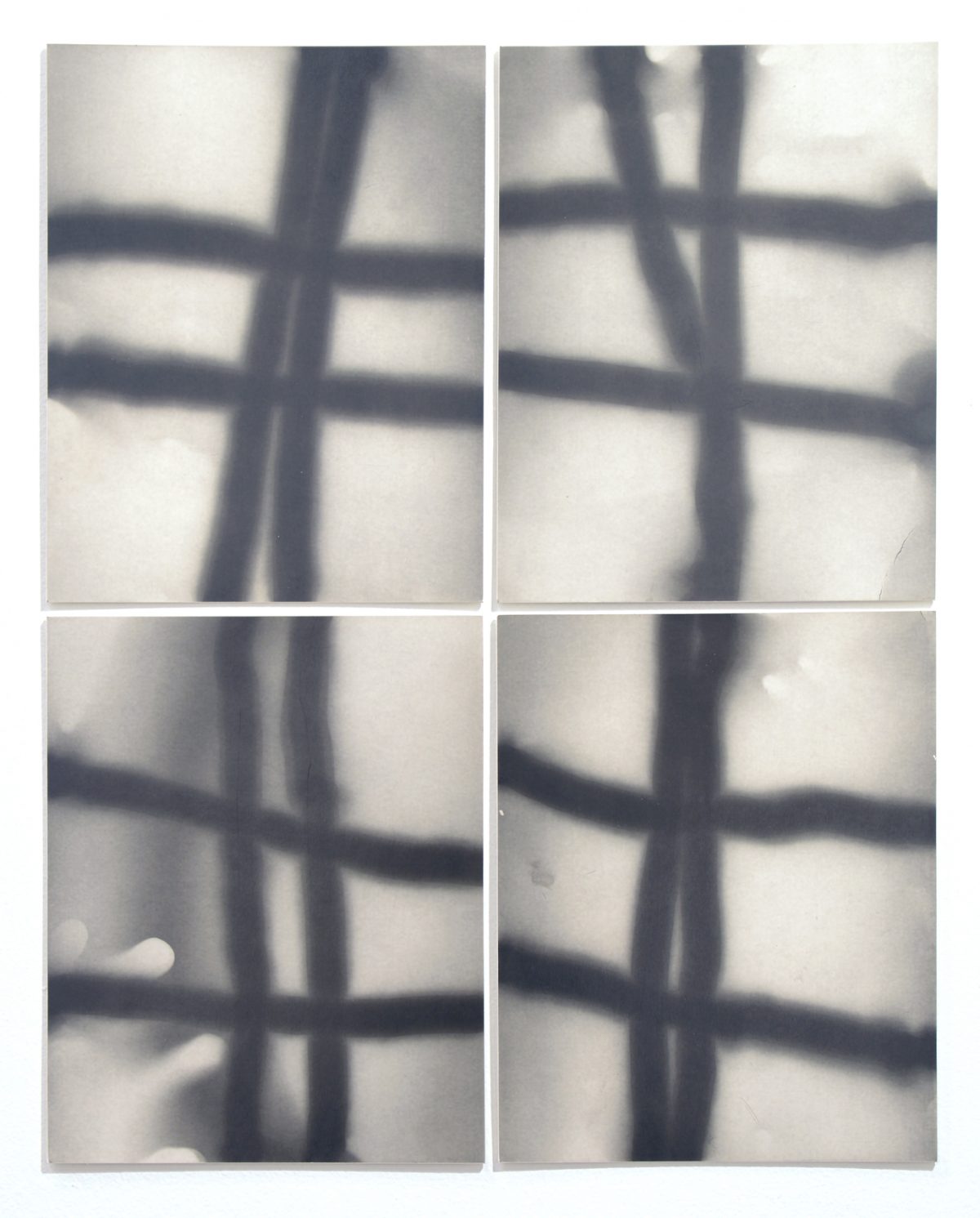

While the word “abstract” often connotes bodiless-ness or the absence of the physical, the abstract drawings of Clifford Owens at CPM Gallery are concretely tactile. Using graphite putty packed into bottle caps, Owens, a Baltimore-born artist, created thirteen 30-by-20-inch drawings in which the viewer can see the thick texture of the medium streaked across each sheet of paper.

One might be tempted to play Rorschach with these large black and white pieces. Many are smudged or smeared. But the attempt to discern a recognizable shape would detract from the more provocative act of simply considering the movements of the artist’s putty-filled bottle caps that made these lines and marks in the first place. Viewed as movements, these abstracts are maps that retrace Owens’ process, the steps he took to arrive at the finished series.

The title of the show, Skully, comes from a popular game Owens played as a child in Druid Heights, just a mile away from Bolton Hill, where this new gallery (run by artist Vlad Smolkin) is located. The game seems a hybrid of shuffleboard, hopscotch, and marbles, where the board is drawn onto the pavement. Players each have a game piece—a bottle cap—that they must move from one square (or “block”) to the next, in numerical order, without having their cap knocked off by another player. There are thirteen numbered blocks in all, with the 13th (the “skull”) in the center of the board.

When Owens was a kid, players took pride in their caps and customized them, packing them with wax, tar, or quarters and modifying their appearance. The cap is the player’s identity, both as a means of literal representation on the board but also as a means of creative expression.