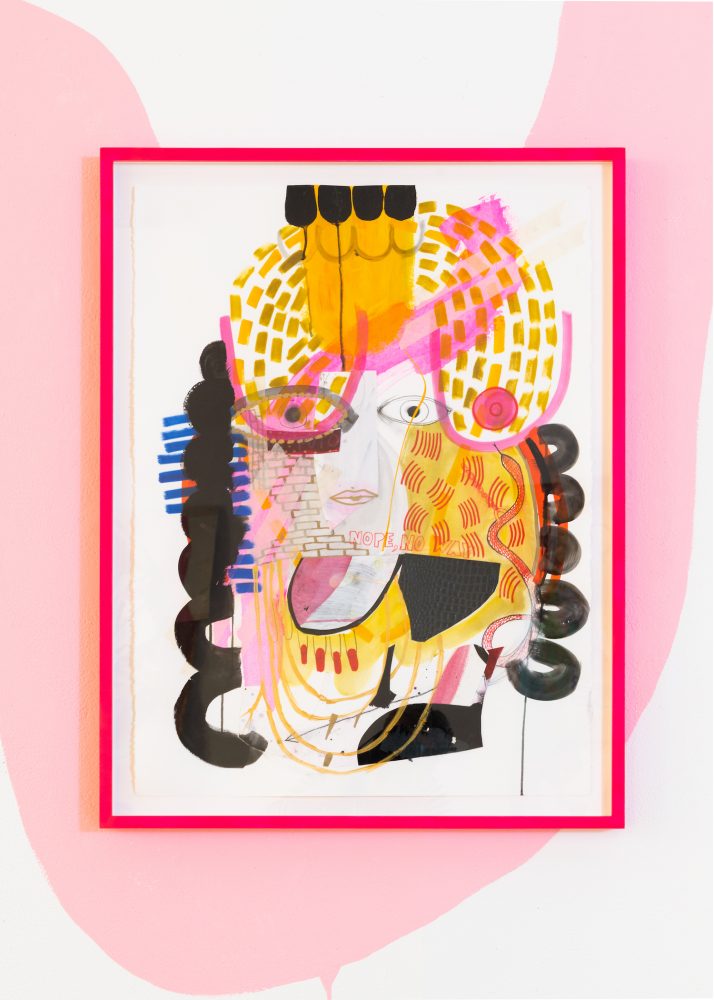

A hand-dyed, pink-tinted canvas pinned to the wall, ripped at its center like an aging bedsheet lying out on the lawn to dry, provides the ground for Jackie Milad’s recent painting “Gold Bars” (2020). Bright yellow fringe gives shade to a smattering of snake-like lines, evil eyes, emojis, text, and patterns that scatter and accumulate like dust across the work and peer out from under layers of overpainting and rosy thread. Offering a cluster of different processes of mark and labor, “Gold Bars” gathers a variety of multidisciplinary moves into one totality, like the practice of musical sampling mobilized for visual means.

This painting forms the basis of a new series of mixed-media works from Milad’s solo exhibition at Julio Fine Arts Gallery at Loyola University Maryland in February 2020, where bold, symphonic constellations of colors, symbols, and historical strategies—from collage and archival methods to handicrafts and graffiti—form a palimpsest of oppositional responses available to artists critical of the medium- and genre-specific silos that so often frame contemporary art.

Through a rich accumulation of visual, textual, and symbolic content, Milad invites us to struggle with the act of making meaning as well as our desire to know, understand, translate, and thus take ownership of her pieces and their many disparate elements.