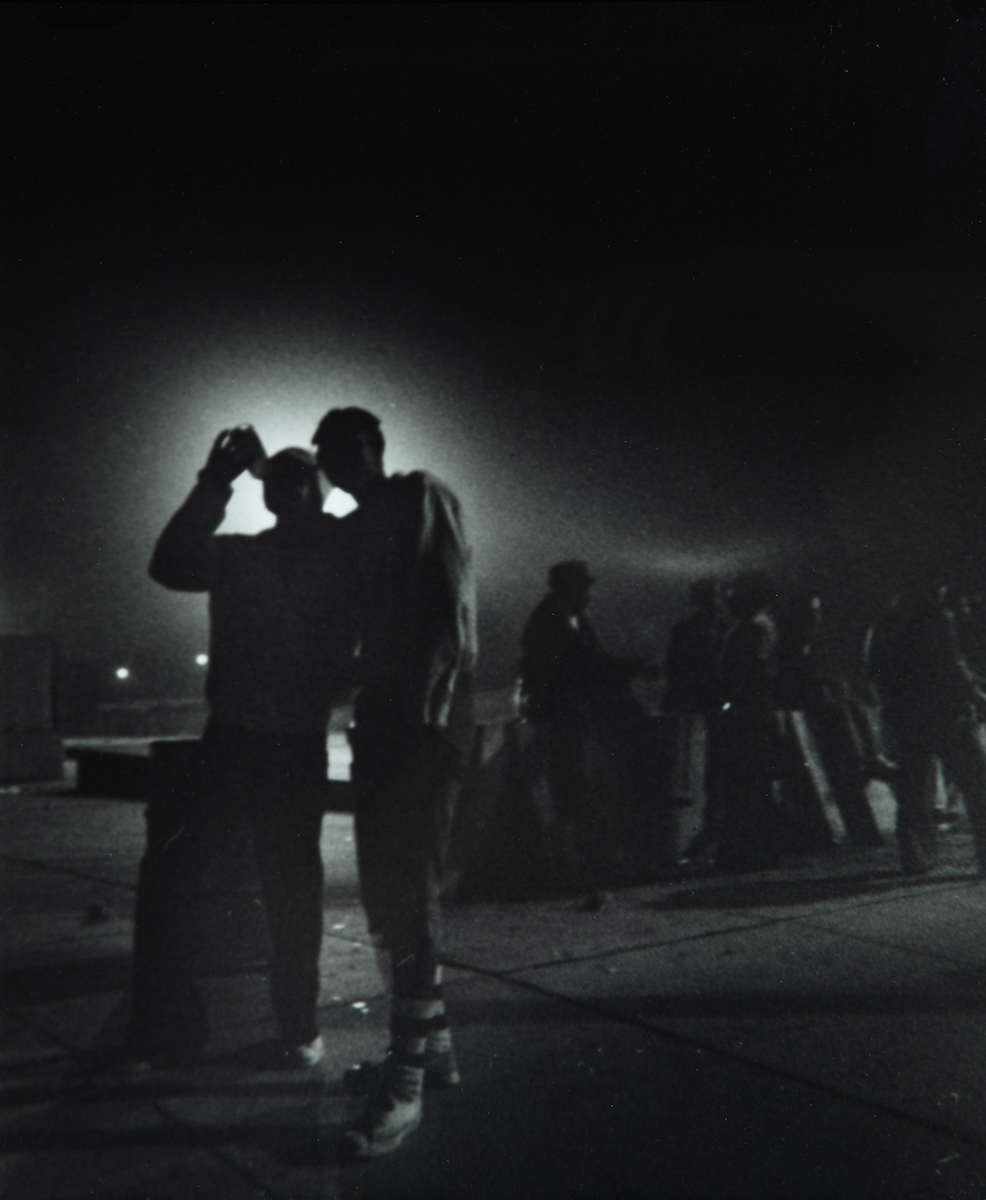

The exhibition of nighttime photography begins with a round, white flash of neon. Reading “VISIONS OF NIGHT,” the sign is an elegant reference to similar ones at venues in the city, from the scroll of the cursive “COCKTAILS” at Club Charles to the blinking neon of strip clubs on The Block. It reminded me of the rush of arriving at a nightclub and pulling out my ID, eagerly awaiting a wristband before I could fly inside into the sound waves of the venue.

Curated by Joe Tropea, Visions of Night: Baltimore Nocturnes at the Maryland Center for History and Culture beautifully and seamlessly integrates Baltimore nightlife of the past and present. The exhibition includes historic photographs taken at night by A. Aubrey Bodine, Richard Childress, John Dubas, Paul S. Henderson, Robert F. Kniesche, and I. Henry Phillips, sourced from the MCHC collections, alongside contemporary photographs by Sydney J. Allen, J.M. Giordano, John Clark Mayden, and Webster Phillips III. Part of Visions of Night’s significance lies in the exhibition text: although “artists have been creating visions of nighttime for centuries… truly successful attempts did not come to fruition or common practice until the 1930s, when technology caught up with artistic vision.”