The simple design and improbable proliferation of the orange belie its complexities. Citrus advertisements are unavoidable around my hometown in Florida, although the only orange trees I’ve seen in the area are singular ones that struggle in people’s yards. On longer drives, a chain of tourist traps advertises live baby gators and fresh local citrus. Seen from the highway, the shop’s bright round oranges and perky lemons arranged on lacquered market stands are attractive. Up close, you realize you’ve been duped by painted styrofoam.

Indigenous to Asia rather than any place in the US, oranges are always available in nearly every American grocery store. They have adapted to growing in the groves of Florida and California, but that is a constant uphill battle for the industry as the climate changes. For my friend and colleague Suzy Kopf, who grew up in California, these concerns have become a major subject of inquiry in her art. Her solo show, Orange Crush at the Gormley Gallery of Notre Dame of Maryland University, is the culmination of years spent pondering the orange—specifically, how such a notoriously difficult-to-grow fruit became cultivated for industry, the infrastructure (farms, towns, factories, logistics) built for production and distribution, and what it has cost and what it has meant.

Orange Crush is a well-balanced show that references midcentury advertising and marketing materials for what eventually became major orange corporations, like Sunkist. Using a variety of media—collages, digital prints, and watercolors, as well as a decorative vinyl installation and a faint but pervasive scent of orange—Kopf explores the “mythology erected by advertising, contrasting facade with fact, sometimes within a single work,” as her exhibition statement says.

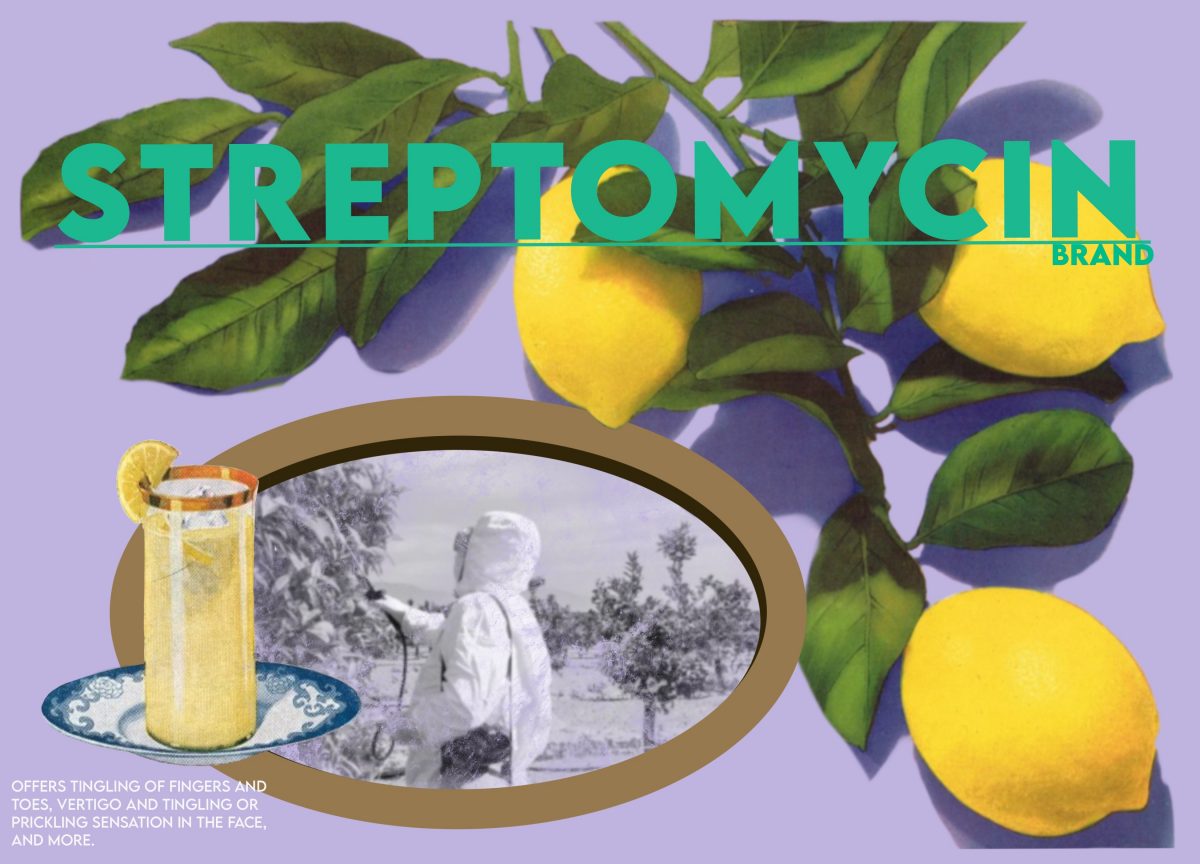

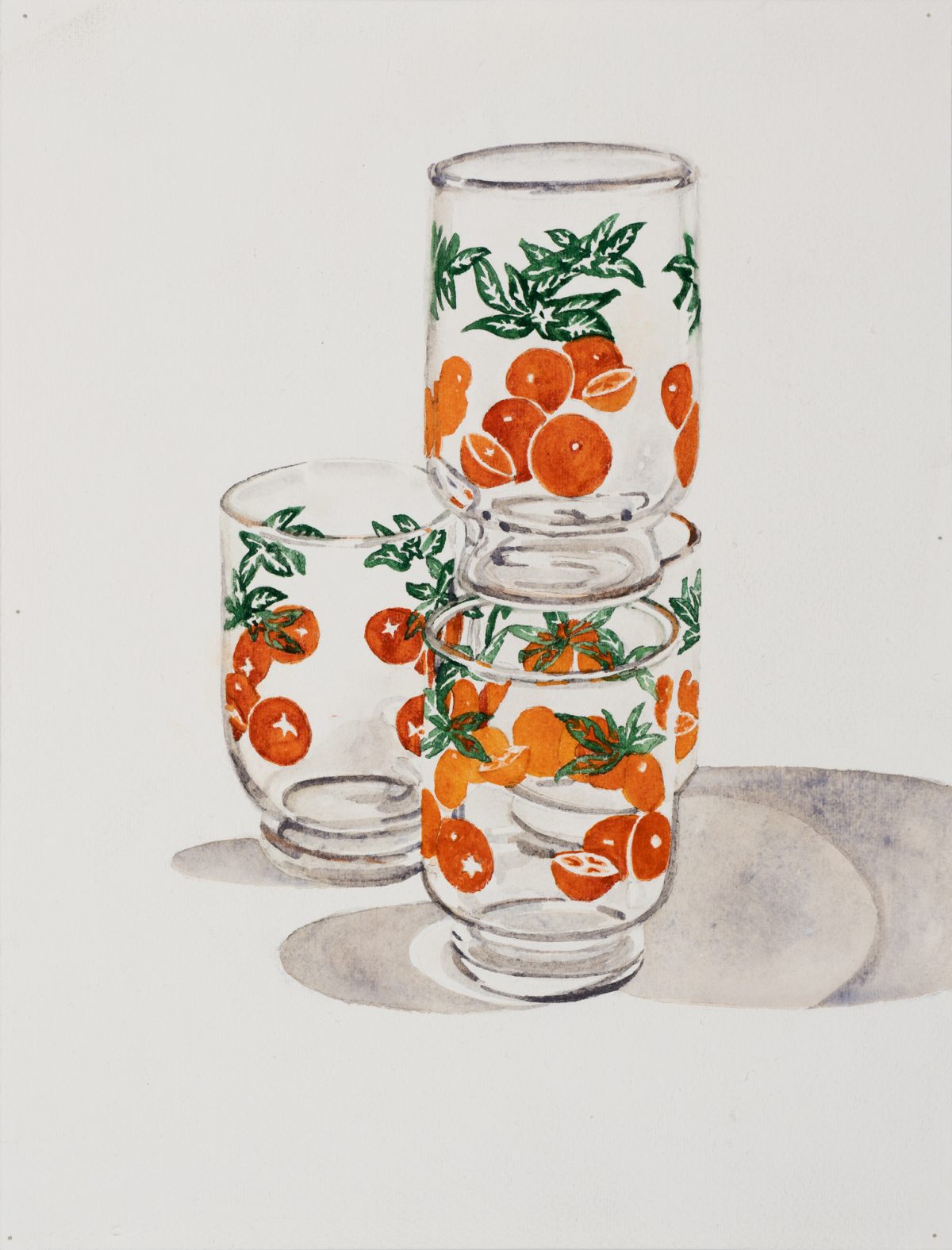

A series of watercolors depict deeply nostalgic “hostess sets”: decorated glassware produced from the 1940s and used exclusively for orange juice. Central in the gallery are wooden crates, stacked and filled with more than 100 slipcast ceramic oranges and lemons; perfect in form but pale in color, they mimic what citrus looks like after being sprayed with pesticides. On the opposite wall, 10 digital prints combine actual citrus-crate labels from the orange industry’s boom era with alternate versions made by the artist that advertise pesticides like arsenic and methomyl. These labels also feature photos of the underpaid, largely immigrant and non-white laborforce of pickers, whose images were left out of company promo; companies opted instead for “orange girls” who, in Kopf’s large-scale prints, pose on ladders with suggestive skirts full of citrus. And finally, a series of collages depict the historic and present-day challenges of orange infrastructure along with illustrations from a 1938 Sunkist coloring book aimed at children.

The work is built on both textual and material research, including a summer 2021 fellowship at the Hagley Museum in Wilmington, Delaware, where Kopf studied orange industry marketing materials like crate labels, logos, and pamphlets from the first half of the 20th century. She also used a grant to hire the artist Hae Won Sohn to teach her how to make plaster slip-cast molds.

Most BmoreArt readers will have already recognized Suzy’s name here as a longtime contributor and former full-time staffer at the magazine. Given these conflicts of interest, it would be impossible for BmoreArt to properly review Suzy’s show, and typically I don’t interview friends. But since I’m from Florida, she’s from California, and this work is about something so central but ordinary in our lives, it seemed like just the right occasion for us to talk about how we feel about oranges, marketing, the sunk-cost fallacy of the orange industry, and whose home state grows superior oranges.