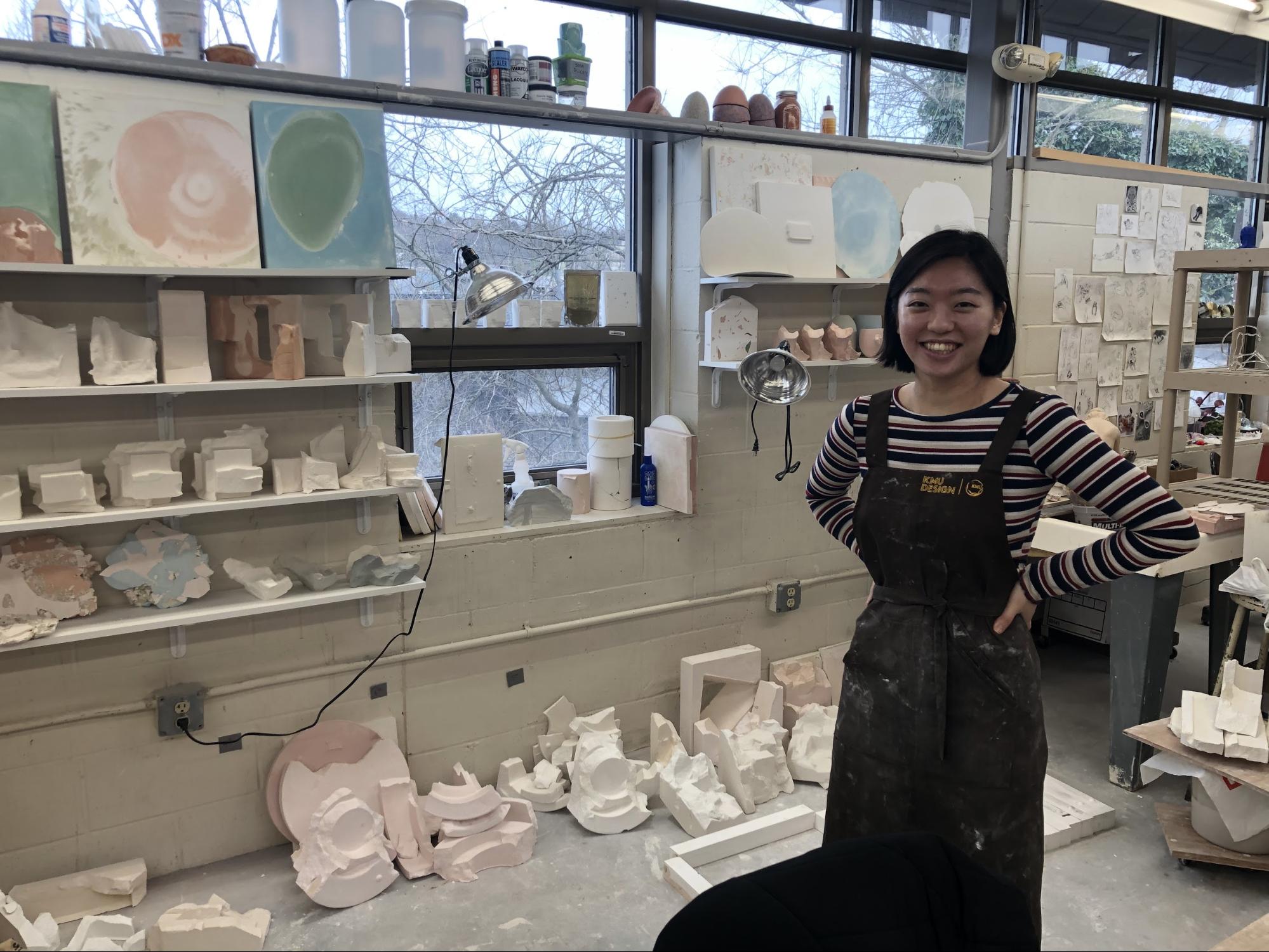

Hae Won Sohn likes breaking things. In her studio at Baltimore Clayworks, she’s constantly creating plaster molds, casting pieces, and breaking them to create new assemblages. Engaged in the dialogue between fine art and craft through sculpture and ceramics, these new works feel like precious relics unearthed in some sort of archaeological dig. For Sohn, the work is about process, evaluation, and experimentation.

A graduate of both Detroit’s Cranbrook Academy of Art’s exploratory MFA program and the College of Design at Kookmin University in Seoul, South Korea, Sohn’s exploration of the limitations of plaster and porcelain runs deep. I visited Sohn’s studio this past February to talk about process and material and what’s next for her practice.

Suzy Kopf: How did these plaster works originate for you?

Hae Won Sohn: I’ve been experimenting with oxide pigments mixed into the plaster and I ended up with a lot of leftovers. That’s how I started to think, instead of just throwing them away, they’re also a part of my studio practice; they become a trajectory. It kind of indicates how my studio is working through the leftovers. These pieces are pretty fragile so they need an extra structure to hold it together. I was thinking about resin, so it kind of looks like it is floating inside the block. I don’t finish one piece and then move on—it’s more like they’re all working up at the same time and then finishing at the same time. I have a lot of pieces that are just maturing in the studio to see what the next step is.

I start with a basic form and then I make a mold out of it, break it, and splice it together to make the first prototype. Each of the pieces has separate molds. Then they get combined to make the prototype and then I make another mold, break it open and select one of the broken pieces of molds, and then combine it to the second prototype. So, each one of these is unique, but they’re building on the same process. It’s evolving through the broken pieces of molds. And you could only make one.

I started making molds in undergrad to work with multiples, but now it’s kind of odd since I’m using mold-making techniques in order to arrive at a unique piece. It’s an excessive process, but that’s how the form ends up really abstract because I don’t really have control over how the mold is going to break. It’s the material that’s doing its thing and I’m only doing this selection.

Are all the works entirely made of plaster?

They are solid casts of hydrostone which is a kind of plaster that has less water absorption. It has some fiberglass mixed into it; it’s more of an industrial plaster that is really hard when set. I use hydrostone for the casts but I use normal plaster for the molds because it has to be easier for me to break open.

When I have some mixed colored plaster inside the bucket, rather than just draining it out or throwing it away, I pour it onto a glass sheet, and they kind of form a floral pattern in the center, and then they just naturally spread out. Then I flip it upside down and build a cuttle board around them and whenever I have a new batch of mixed plaster leftover I add it on to it until it fills up the block. I called this series my plaster paintings. They have very different aesthetics compared to my sculptures but it’s interesting how it takes the same concept but it comes out in different forms.

You’ve been so productive in the studio since the last time I visited a year ago! How do you get this much work done?

My process and my final product are always mixed together since I work simultaneously on many things. I don’t feel productive because I don’t always get to see it until I arrive at the final product. Unless I have an exhibition or a studio visit—that’s when I start to process what is actually done.