When one sees Amy Cavanaugh and her infectious smile greeting visitors at Maryland Art Place’s spotless galleries, it’s not easy to picture her playing in bands at the infamously grungy punk mecca CBGB. But when we look at Cavanaugh’s journey from classically-trained cellist to indie rocker to community organizer to arts administrator, we get a richer picture of one of Baltimore’s hardest working cultural leaders.

In 2012, Maryland Art Place (MAP) was located in a cavernous rented space within Power Plant Live, but MAP’s Board of Trustees had decided to relocate the arts organization back to 218 W. Saratoga Street, its original home in a building owned by the organization. They needed a leader to create and enact a feasible plan to accomplish a successful move and renovation of the original building. When Amy Cavanaugh was hired as its Executive Director in 2012, she had a background in arts administration as well as in cultural economic development, which made her uniquely prepared for the multitude of challenges that lay ahead, in establishing MAP as a central anchor in Baltimore’s Bromo Arts District.

As with many of us working in the arts, Cavanaugh started out her career as a practicing artist. She was raised in the Washington, DC area, with the majority of her childhood spent first in Georgetown and then in Fairfax, VA, which was mostly fields and farms back then. From the age of nine, she studied the cello, with a classical training that continued through secondary school, culminating in her participation with the National Symphony Orchestra in her junior year at Lake Braddock Secondary School.

She earned a scholarship to Catholic University in Washington, DC, where she studied cello with Bob Newkirk, principal cellist for the Opera House Orchestra at the Kennedy Center and after that, returned for a Master’s Degree. However, a year in she decided to switch her focus from solo performance to chamber music because she much preferred to play in groups, but this concentration was not available at the time at Catholic U. Cavanaugh decided to drop out of grad school and spent a year learning how to improvise.

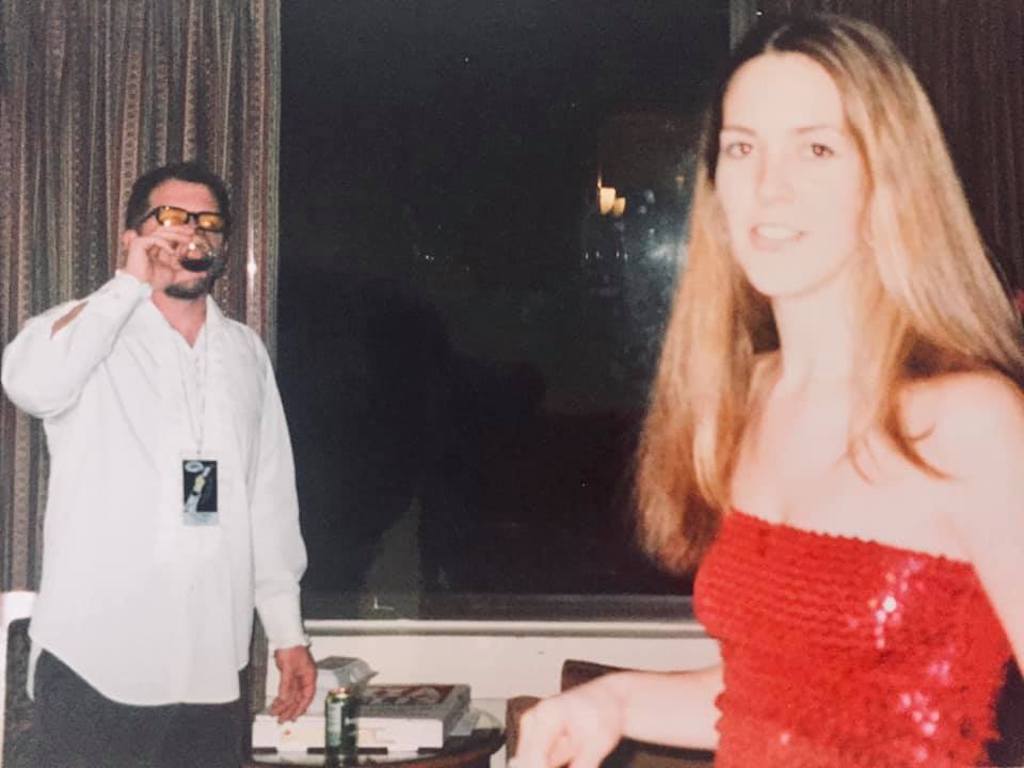

“I forced myself to play with different groups, and this is how I met the members of my very first band, called 24 FPS (Frames Per Second),” Cavanaugh says. They released their first EP in 1996, and performed in clubs on the East Coast up into the early 2000s.