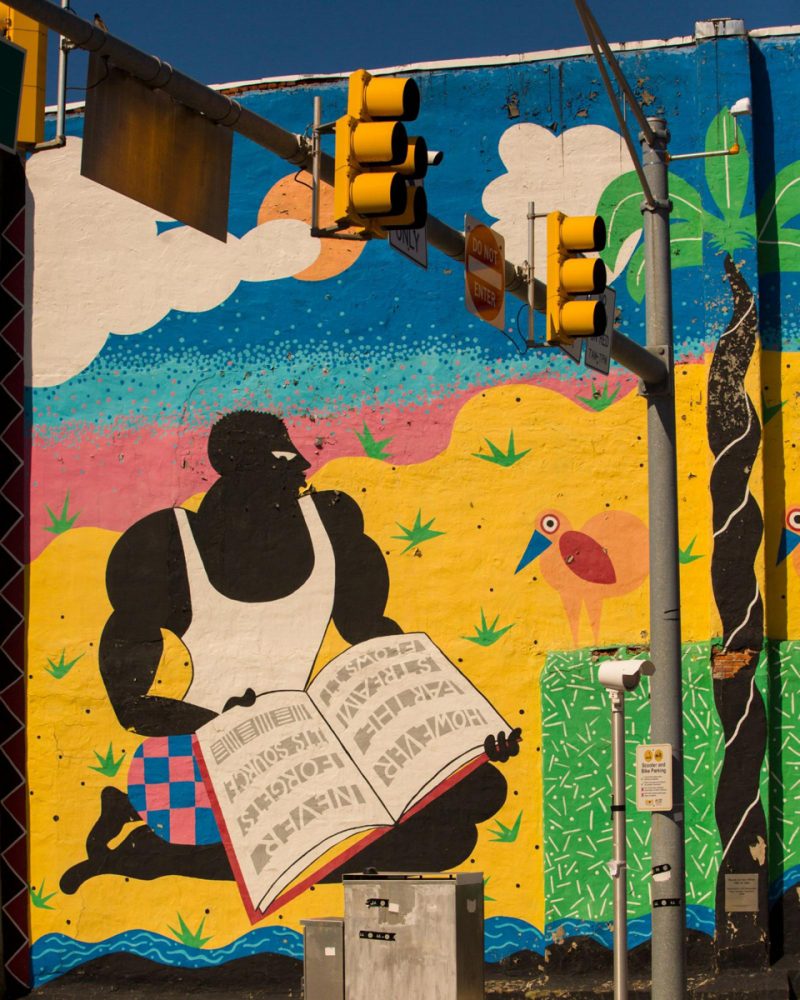

If you’re ever at a red light at the intersection of E. North Avenue and Harford Road, take a moment to look around. Hopefully you’ll get a good view of two of my favorite murals in town, painted by Baltimorean Tom Miller. On one side of the road there is an expansive wall depicting “Children Playing”—a zooming bicyclist, a boy enjoying ice cream on the stoop, a toddler with beads in her hair, and white marble steps—a recurring detail in Miller’s paintings.

On the other side of the street there is a big, black, and beautiful man sitting on a sandy beach. Perhaps he is on a tropical island, as a palm tree stretches up the wall and colorful birds look on nearby. He is relaxing with a book in hand. The open pages feature a Nigerian proverb: “However far the stream flows, it never forgets its source.”

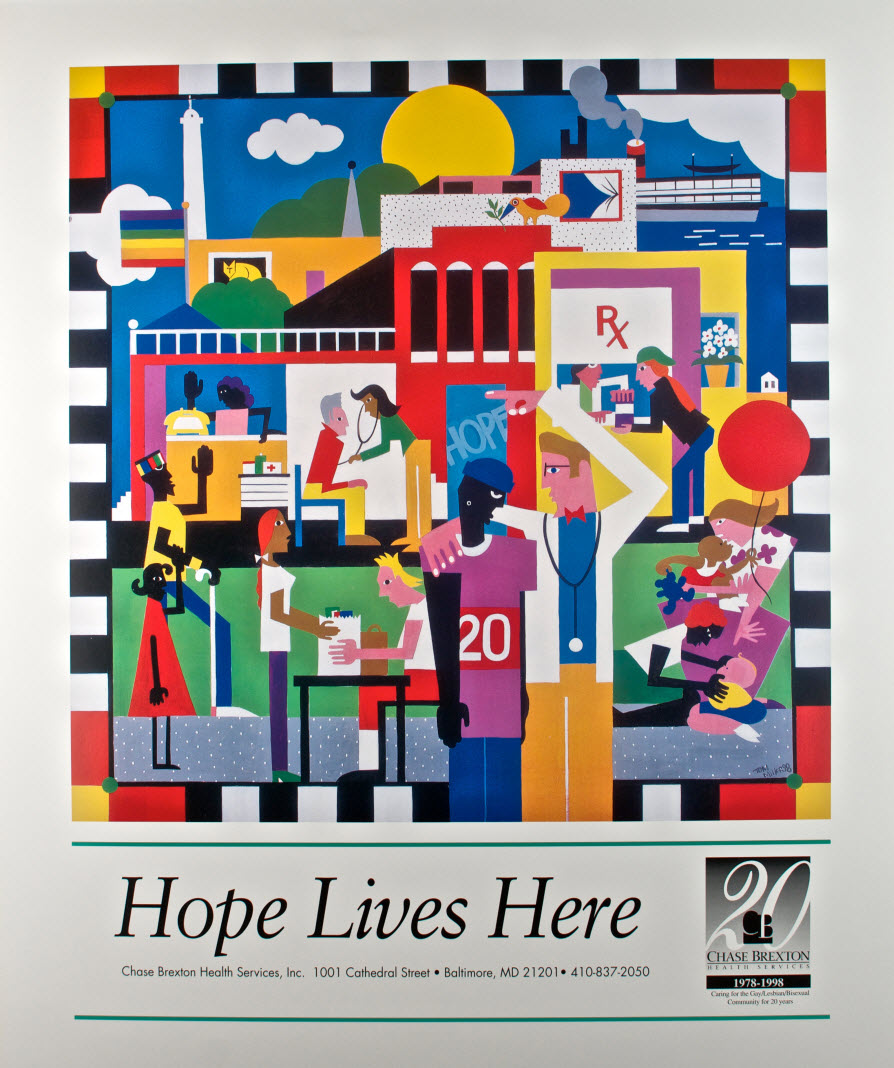

Baltimore was the primary source for Miller’s inspiration. To this day, his creative stream still flows throughout the city. He was born here, grew up in Sandtown-Winchester, went to Carver Vocational Technical High School, studied at MICA, taught art in Baltimore City Schools, and passed away at the Joseph Richey Hospice. Miller highlighted everyday scenes and landmarks through his art, as evident in his screen prints “Maryland Crab Feast” and “The National Aquarium in Baltimore.”

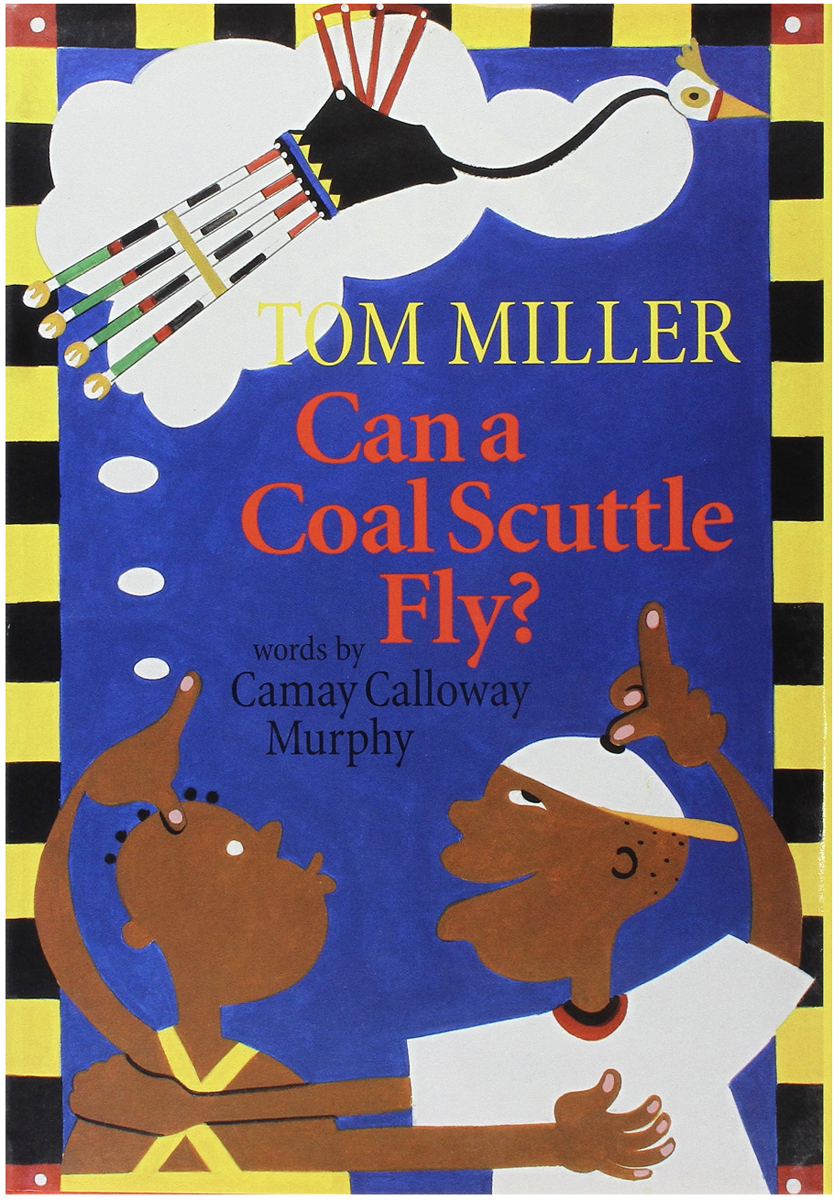

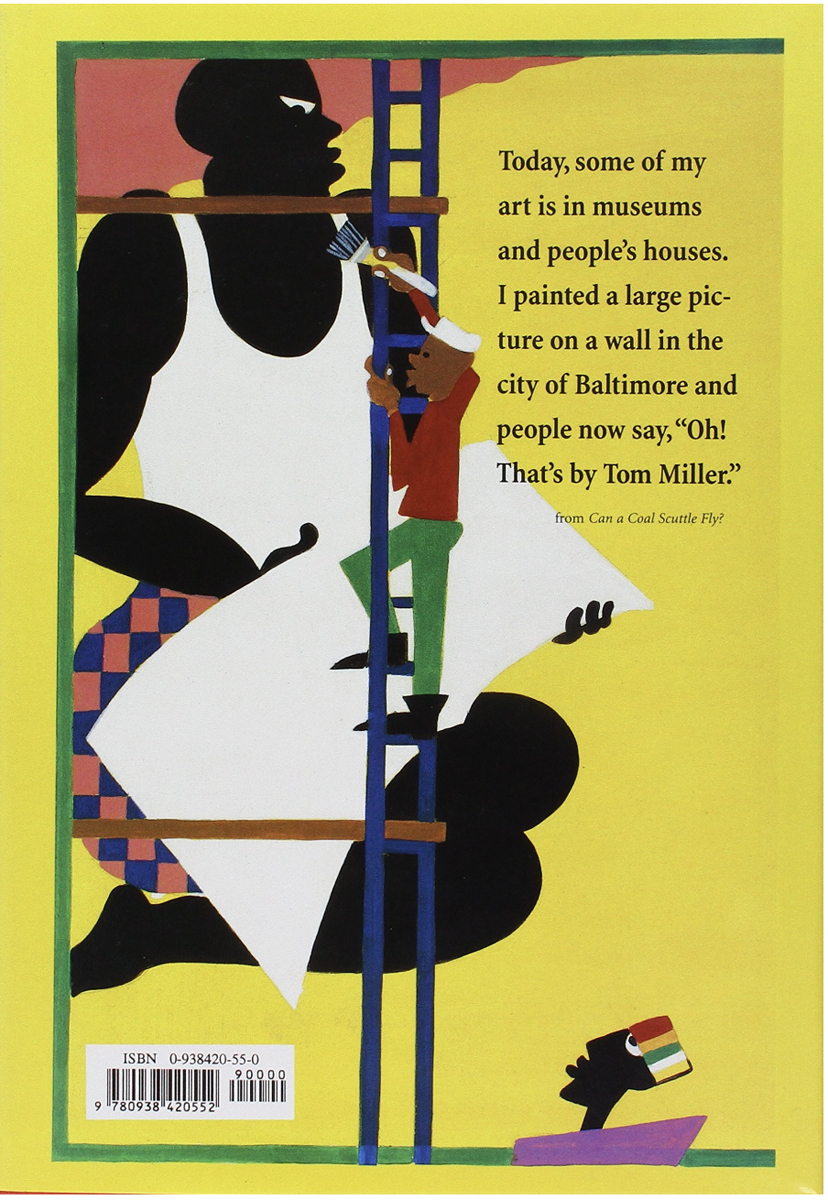

I first learned about Miller through the book Can a Coal Scuttle Fly?, a biography written by Tom Miller’s friend Camay Calloway Murphy (daughter of Baltimore-born jazz musician Cab Calloway). Miller illustrated this children’s book which tells a chronological story of his joyful upbringing as well as his journey on becoming an artist.

The story begins with an infant Tom coming home from the hospital. “My mom says I liked color from the beginning. She brought me home from the hospital in a bright red baby blanket. When I peeked out from the blanket and saw the colored brick houses and rows and rows of white marbled steps, my little feet began to kick and my fists pummeled in the air with joy.”