As a Baltimore city-dweller, what disrupted my sense of normalcy upon my first visit to Glenstone was not the art. Instead, I was jarred by the impact of a meadow, expansive and diverse in vegetation, buzzing and jumping and rustling with wildlife, all peacefully illuminated below the wide, cloudy sky.

Removed from the city—which often speaks its language in construction cones and traffic lights, helicopters and sirens, layers of commerce past and present—I did not just see an alternative way of life but felt it, like an instinct suddenly activated. Watching a white, hairy caterpillar going about its business on a tree, I wondered, with a twinge of estrangement: When was the last time I’d seen such a thing? Or had the time and space to do so?

Glenstone is an art museum in Potomac, Maryland, that tends to its outdoor environments as much as the indoor ones that house much of the art. The major difference between visiting Glenstone’s grounds and hiking in a natural environment like the Blue Ridge Mountains is that the museum’s 350-acre campus is cultivated, even though the land seems to be utterly wild.

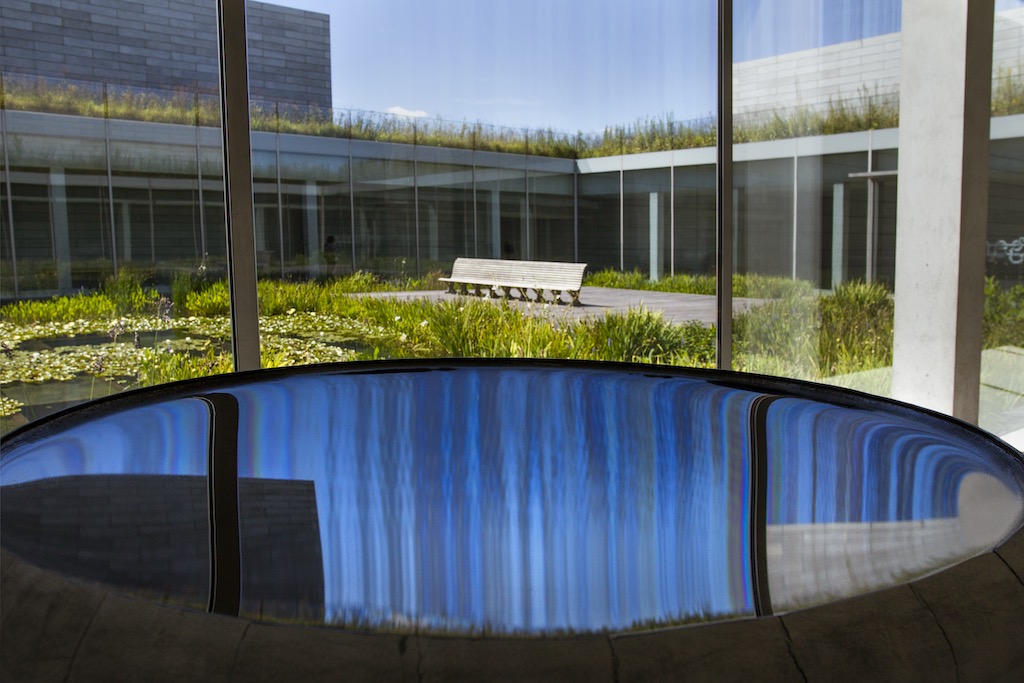

The grounds are man-shaped, designed by landscape architects Peter Walker and Partners, and Glenstone encourages visitors to think of the landscape through the lens we usually reserve for inside a museum. Glenstone’s largest indoor exhibition space, a series of linked pavilions designed by Thomas Phifer and Partners, devotes an entire room (the only one with a window looking out) to contemplate what takes place outside the walls rather than within.

Trevor Garbow, Glenstone’s Deputy Landscape Superintendent, emphasizes the tremendous effort of nurturing native plants while keeping invasive species, such as Japanese stiltgrass, at bay. Since Glenstone began cultivating the land twelve years ago, a huge diversity of native plants has thrived: little bluestem, purple top euphorbia, rattlesnake master, milkweed, and mintweed, to name a few. A host of new insects soon followed, attracted to a feeding and nesting ground that had previously been a barren monoculture.