The line of demarcation between “folk” and “fine” art in America is centuries old and extends far beyond the founding of our nation. The former, which includes practices like needlework, woodwork, basket weaving, and ceramics has long been considered the lesser of painting, sculpture, and other works that align with art world standards.

There’s no coincidence these works are often gendered, associated with the home and “feminine” qualities, racialized, classed, thus deemed “unrefined” and considered “skilled labor,” more akin to artisan than artist.

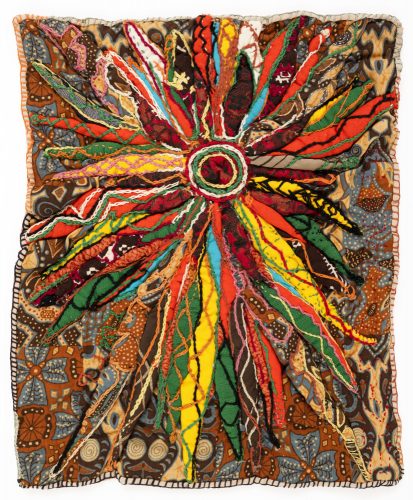

Black cultural production has been heavily marginalized within the art historical canon. This is especially true of those whose practices have been steeped in vernacular. Somewhere in the midst of the second wave of feminism, gay rights, civil rights, and the subsequent Black power movement, several artists found inspiration in a return to craft.

An example can be seen in Faith Ringgold’s use of textiles for her Feminist (1973-1993) and Slave Rape (1972) series’, both precursors to her story quilts. Though slower to catch on, curators and scholars began turning toward rural roots, expanding critical discourse and establishing pathways through the hierarchical landscape.