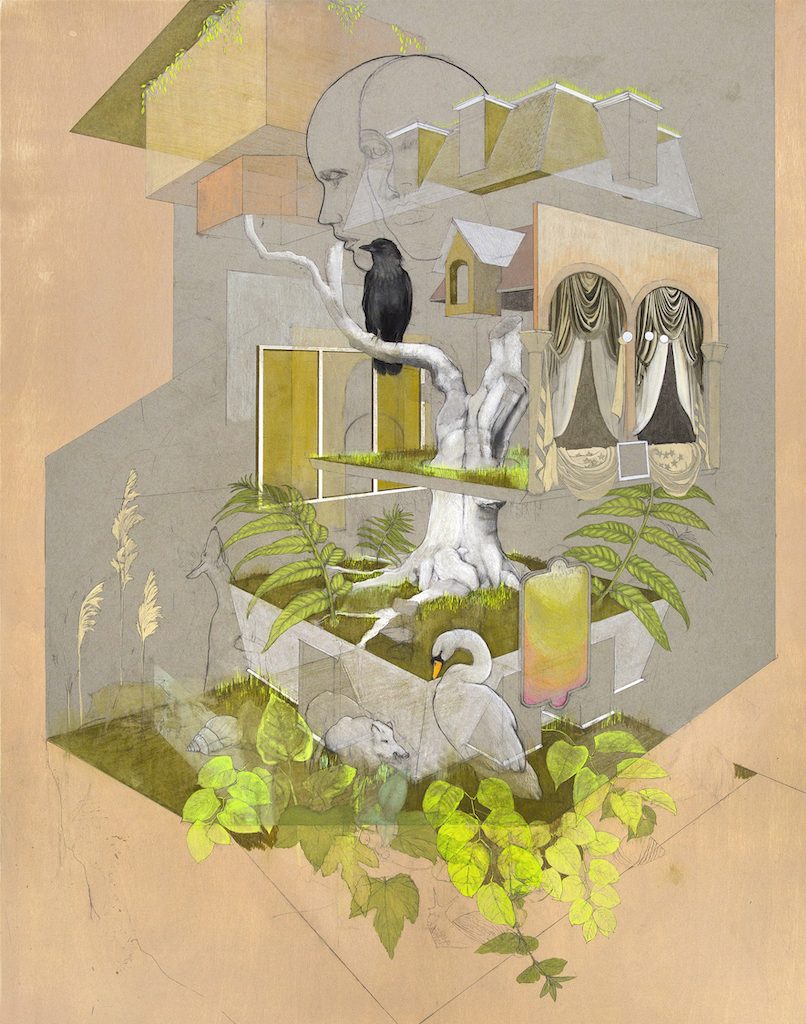

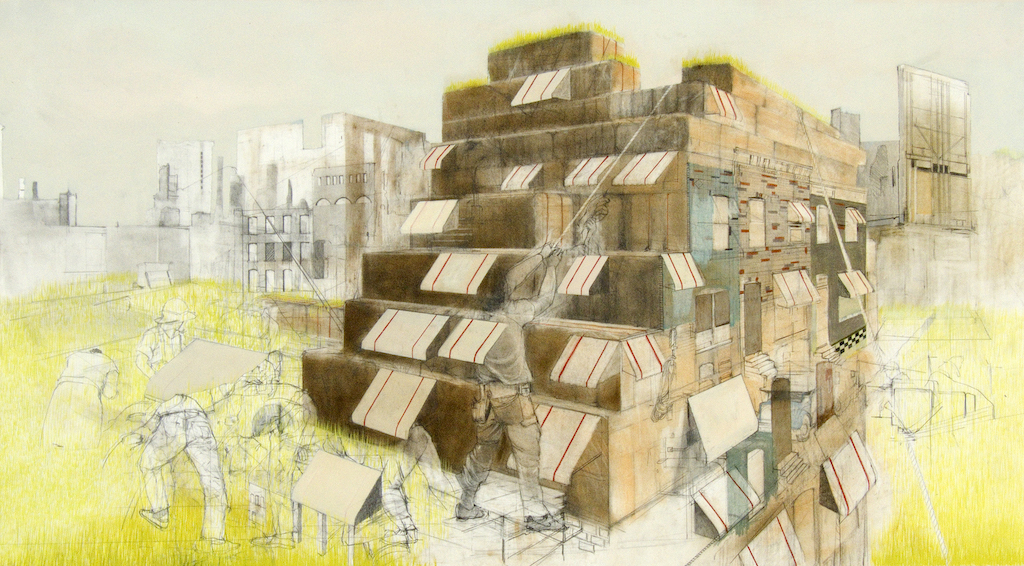

The cultivation of an artist’s career can be a winding journey, and in some ways Alyssa Dennis’ path has come full circle. The Baltimore-born artist first established her palette as a painter and architectural illustrator with an interest in permaculture and sustainable building while still an undergrad at MICA. After graduating with a BFA in General Fine Arts, she traveled. From New Orleans, then to Mali, New York, and Peru, she discovered a through line to herbalism, and established a practice of “restoring the human soul in its integral presence with the vital powers of the earth.”

“I had a teacher once who told me, ‘All we are is our patterns.’ It was really profound, and my response was,‘Okay, how do I make the right patterns?” says Dennis.

“I’ve always had this curiosity for what was ‘other,’ and I felt like art was a way to see what was secret about life.” Dennis discovered some of those secrets during her formal art studies at George Washington Carver Center for Arts and Technology, MICA, and Tulane University, and still others working in green construction, but the pieces all came together while completing a certificate program at New York’s ArborVitae School of Traditional Herbalism in 2020.

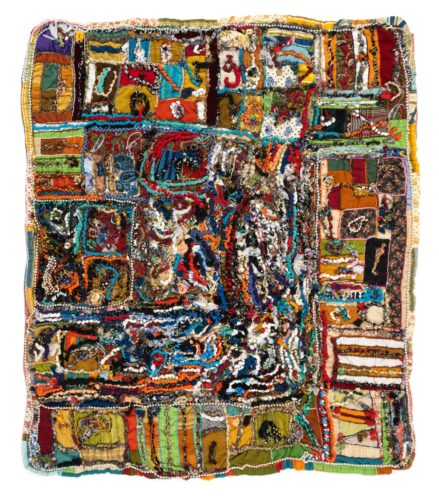

“Art and herbalism are my chosen vehicles to understand and express systems of oppression upon the planet, those that negatively affect our health and the environment,” says Dennis. “I call this the ‘overculture,’ where we only see reflections of ourselves in the world. Architectural interests and imagery have been a big part of how I visualize and express the overculture.”