The French poet and statesman Alphonse de Lamartine once complained that museums are cemeteries of the arts, and it’s not hard to see why—separated from their original contexts, the objects in a museum can feel lifeless and embalmed: static monuments to a distant past. But even cemeteries, in the right conditions, can be surprisingly powerful and moving places. And if we look closely and think creatively, the most inert and seemingly remote museum object can become surprisingly vivid.

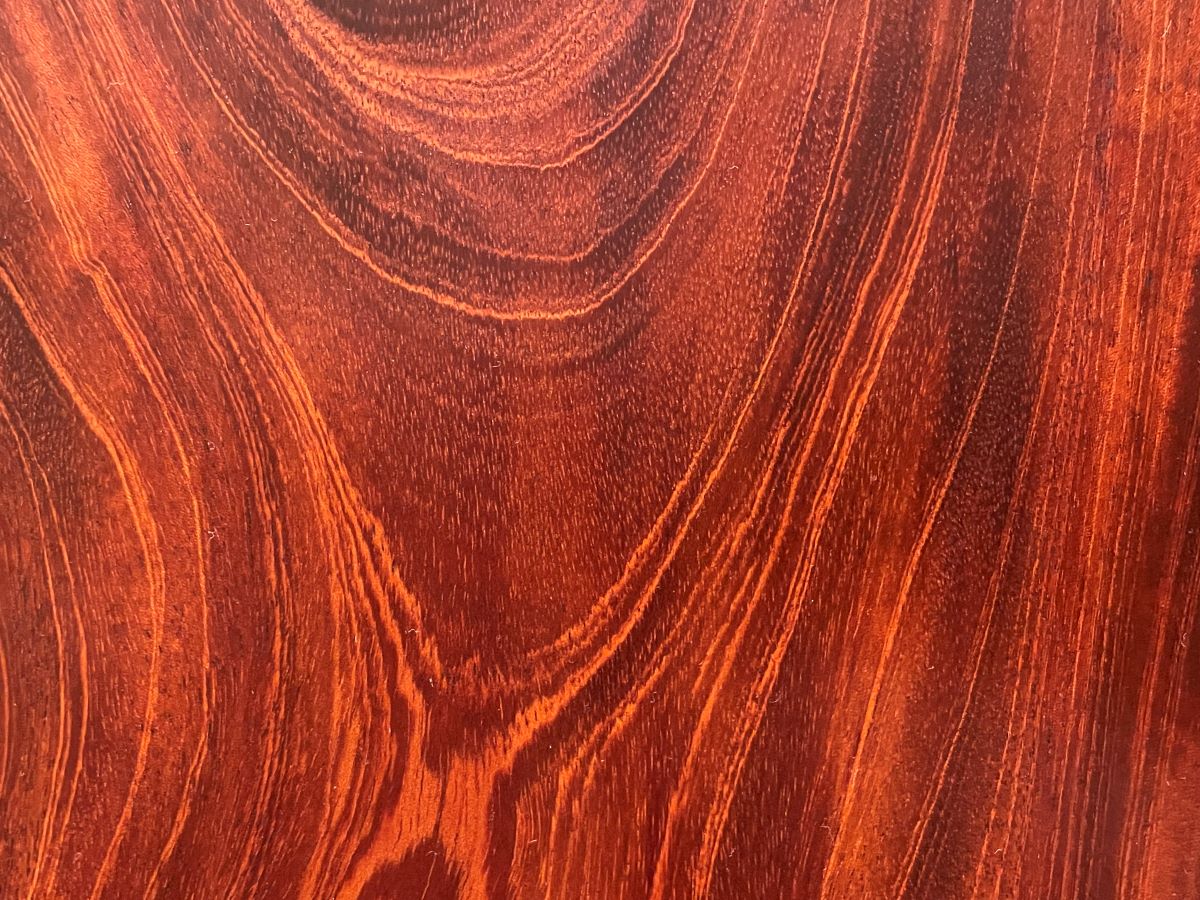

The Duffield clock, which was made in Philadelphia in around 1770 and is currently on view in the Baltimore Museum of Art’s American Wing, offers a useful example of what I mean. At first glance, it can feel intimidatingly formal: at nearly nine feet tall, it’s huge, and its sleek surfaces, made of wood, brass, and glass, suggest dignified sophistication. Clocks like these were among the costliest domestic objects in colonial America, and they were often placed in the corner of a public room, as a subtle but visible demonstration of a privileged family’s relative wealth.

But their placement was also motivated by convenience. Set in a parlor or on the landing of a staircase, a clock could be quickly consulted by family members, easily maintained by servants, and occasionally admired by guests—and heard throughout much of the house. Sometimes, clocks were also placed in kitchens, in order to help measure cooking times. More often, though, they served as points of reference for entire households, at a historical moment when personal timepieces were still rare.