Franconia Notch is a glaciated valley in New Hampshire, and Drozd is interested in the ways glaciers move and sound as they drift and eventually disappear. In fact, there is no ice present in this work—just granite sourced from a quarry in the glaciated valley. The presence of the glacier is spectral, like a star that has blinked out of the sky. Drozd orchestrated her sculptural installations to address the dual ideas of circuits and extinction: The notes from the piano strings vibrate against the granite, play then pause then play on loop. Though the sounds may seem cyclical, the vibrations are subject to changes in temperature, or humidity, or airflow from people filling a room. The sound, ultimately, is not static but mutable. Fleeting.

As Drozd chose thick, bass piano strings for her work, the sound produced is a deep drone rather than the ethereal note a harp string might have made. This resonating drone might be considered meditative or lulling, but there is also an ominous quality, as if the sound were the dial tone for the universe—and Drozd is unsure if anyone will start to dial. Though one could easily mistake the sound as the banal mechanical hum of industry, given the environmental themes of the work and the planet’s escalating climate crisis, Franconia Notch 01-12 asks us to have a human response.

Scientists often use personified language when referring to a glacier’s life cycle. A healthy glacier grows each year more than it melts; a glacier’s memory is stored within its layers and disappears when it melts; when part of a glacier stops moving altogether, it is considered dead ice; when Iceland’s Okjokull glacier went extinct, geologist Oddur Sigurðsson held a memorial service and issued a death certificate. Drozd acts in the same capacity in here, giving the glaciers of New Hampshire a much-overdue funeral song.

Perhaps what is most interesting about this editioned work is the tension created between the ephemeral nature of Drozd’s art, the instabilities of the natural world, and the solidified object-ness of these 12 pieces. The numbered, black weather-proof cases protect and preserve the artwork but also codify and conceal it. Will the owners of these editions choose to display the case, lid open, to showcase the aesthetically pleasing geometry inside? Install the piece on a wall and allow the piano string to reverberate and come alive? Keep the case shut and stored away, conserved but not in use?

One could ask a similar set of questions about our human responsibility to the planet. Where is the line between preservation and intrusion? Between protection and obstruction? Can one own an artwork that is also a piece of nature? It is noteworthy that the Franconia Notch 01-12 editions are the first artworks Drozd has ever needed to sign, an act she found both novel and disconcerting.

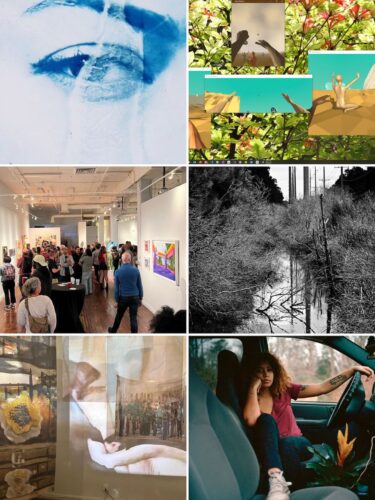

I was surprised to learn that many of the people who attended CPM’s edition release told Drozd which one of the cases they would pick out to take home with them. But upon further reflection, I should have expected it. Afterall, engaging in an act of commercial evaluation is as human a response as any. And it’s precisely this paradoxical desire—to encase experience—that makes CMP editions so compelling.

Note: CPM Edition Release: Franconia Notch 01-12, by Luba Drozd, will be on view through July 15 by appointment.