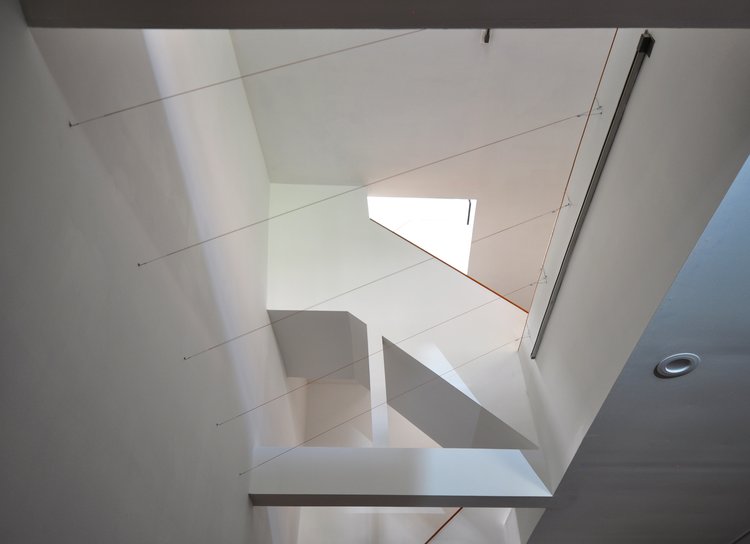

EV: Let’s discuss the objects and their relationship to space, but also making the objects and making the installation. What was interesting to me was that you could see the steel and the strings, and the motors that activate the sound, but the rest is hidden. But there’s an implication that all the pieces are connected (and Vlad revealed that all of the pieces are connected). I kept thinking about you making these pieces, Luba, and installation as a labor. Let’s talk about the relationship between hiding and revealing, and your priorities. How would you like your piece to be experienced visually?

LD: What has happened previously (or how people perceived my work) is that I make everything obvious. There’re wires you can see; as you said, you can see the motors. And still, the fact is that the sound is created via vibrations; it’s not prerecorded, it doesn’t have speakers. All the sound is analog vibration resonance, a reflection of sound, even if everything is presented. There is confusion in the space about what’s happening overall with sound.

I used to be more concerned about making everything hidden, like the wires. I wish I could hide the motor, but it seems not very important. What’s important is the experience of hearing and seeing the space, and how the pieces relate to architecture, to natural light, to how the person moves through the space as they enter it, and how the parallax changes as the person travels through space. Some things align; a lot of things are aligning with corners, depending on your position. These alignments are how I structure the work. Certain pieces should be viewed from a certain angle, in my mind. So everything is constantly connected: perception of visual information and sonic audio perception.

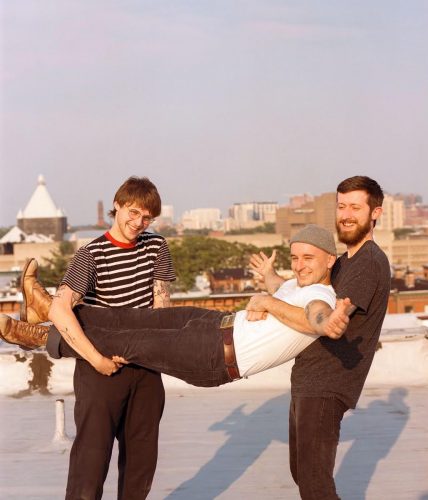

EV: Talk about how you two worked together. How did you decide, Vlad, on Luba’s work for your gallery? Why did you think it was a good fit?

VS: That’s both a really simple and complicated question in terms of how these things come together. In a very general sense, the site specificity of Luba’s work aligns with my vision of what a gallery is. Every exhibition is site specific. Sometimes we place that fact further back from the immediate perception of the viewer, but Luba brings that to the front. So this show aligns with the kind of participation that I want people to have with any exhibition. Luba’s work makes that inevitable—and I think that mostly has to do with sound. Because you can close your eyes but there’s something about sound that goes into your body, even if you plug your ears. So, I think the psychic aspects of art in general are operating in an overt way in her work. That’s interesting to me.

EV: Luba, is there anything you found specifically interesting about working with Vlad? Were you excited to collaborate?

LD: I came up once or twice to take pictures and 3D-scan the gallery so I could have an idea [of the space]. I made a 3D model and looked at it and thought about how the space operates with the viewer in there. And then at the beginning of July, I came up to Baltimore and stayed for two weeks off and on, installing the work.

We haven’t worked together before, and it was great. I felt like there was a grounding that happened in our collaboration on making this piece, or just working with Vlad; everything seemed aligned. There was a centering of thought that happened in making the work. The space is incredible for it; there are sonic pockets in space and that’s really great.

VS: To add to that: anyone that’s been here knows the way the sound bounces off the walls and the spatial dynamics of the architecture are perfect for working with an artist dealing with sound, with architecture, and with industrial materials. You’re addressing the bones of the house and using the building itself as an instrument. I also have a background in music and have paid attention to what sound does in the space. So when Luba started installing her work, I was bringing my background, my history with sound into it as well. And I was fascinated by it. I mean, Luba heard me humming and singing and snapping my fingers, walking around trying to relate to the sounds that her objects were making through my own processing system. And a lot of people do that, as you’ve seen. I loved when Joyce Scott was singing here because I feel like you don’t usually walk into a gallery and start singing, but Luba made it an invitation. It was incredible.

LD: That’s absolutely stunning. I have no words. That was spectacular. I’m really grateful that that happened, actually.

VS: With Joyce, she came in and was like, Where’s the show? And then in 5 seconds she just totally plugged in, and then started making vocal sounds in almost a call-and-response way with the work. And she made a point even to say when we were sitting and talking that she didn’t consider Luba’s installation to be a backdrop to her as a solo voice. She was thinking about it more like her participating with the sounds that were there. And that’s obviously an important distinction. I had a sound artist comment on the video that we were both reverberating the world. Everybody’s vibrating the world.