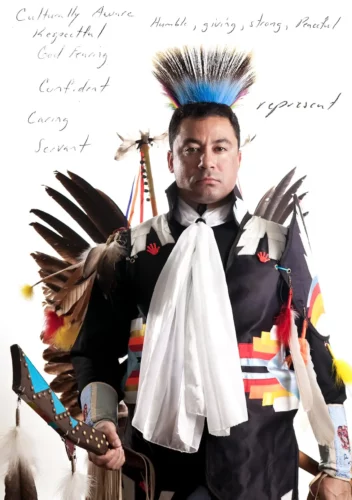

That man’s name is Will Walker and he’s the charismatic founder of the running collective A Tribe Called Run. To say this group changed my thoughts and feelings about what running could do and be would be a vast understatement. I’ve been a runner since I was about fifteen years old, which means that—as I shuffle through middle age—I’ve been a runner longer than I was a non-runner. But I never ran cross country or track and only recently started running as a social activity.

If you asked me why I run, I would probably tell you that I started around the time depression and anxiety kicked in so hard that I couldn’t sleep at night. I’d probably parrot some platitude about running being “meditative” for me. But now, as I train for my first marathon, I find myself wondering (to paraphrase Haruki Murakami) what do I think about when I think about running? How does running figure into my mental health regimen and my creative work? Is it meditation or ideation or more than that? And, if I’ve spent so many hours of my life doing this one thing, shouldn’t I consider what it means to me?

For Murakami, running is “both exercise and metaphor.” In What I Talk About When I Talk About Running (the running memoir every vaguely literary runner you know has read) he describes his running practice as solitary and uncreative. He doesn’t use his long runs as a way to generate ideas for his novels, but rather as a time to clear the mind and focus on self-improvement. A writer friend recently described Murakami as having an uncanny ability to “write about emptiness,” which rings true of his approach to running. It’s quiet and spare—disciplined, even. And, since the book is a rare example of a novelist writing about running, it’s easy to take it as a blueprint for a creative life that is also a running life. But what if you think—like I do— that running could be much more expansive than Murakami’s approach suggests.

It is also not lost on me that I’m re-reading this book, which Murakami partially wrote in Hawa’ii, as parts of the state are in cinders due to wildfires caused by the climate crisis. In fact, the title of this piece is lifted from Natalie Loveless’ How to Make Art at the End of the World: A Manifesto for Research-Creation, which in turn takes its framework from Timothy Morton’s Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World.

Loveless sees the arts as having a role to play in the contested epoch known as the Anthropocene, or the human-created ever-warming hellscape we now call the world we live in. She argues that the arts “offer modes of sensuous, aesthetic attunement, and work as a conduit to focus attention, elicit public discourse, and shape cultural imaginaries.” I think what Loveless is getting at in her book is that creative practices can be a mode of understanding and rethinking humanity’s place on our ever-warming planet. I wonder what role running might play? But more on that later.