Over the last decade, Baltimore filmmaker and photographer Jonna McKone has developed an extensive body of visual art that has exhibited across the country, spanning portraiture, experimental documentary, music video, and interdisciplinary genres.

McKone’s vision, coupled with a strong drive for collaboration and a desire to explore the “legacies of empire, the fragility of truth, and the land and body as vessels of memory” has already made her a fixture of Baltimore’s art landscape—and she’s continuing to engage with these questions in her ongoing and new bodies of work.

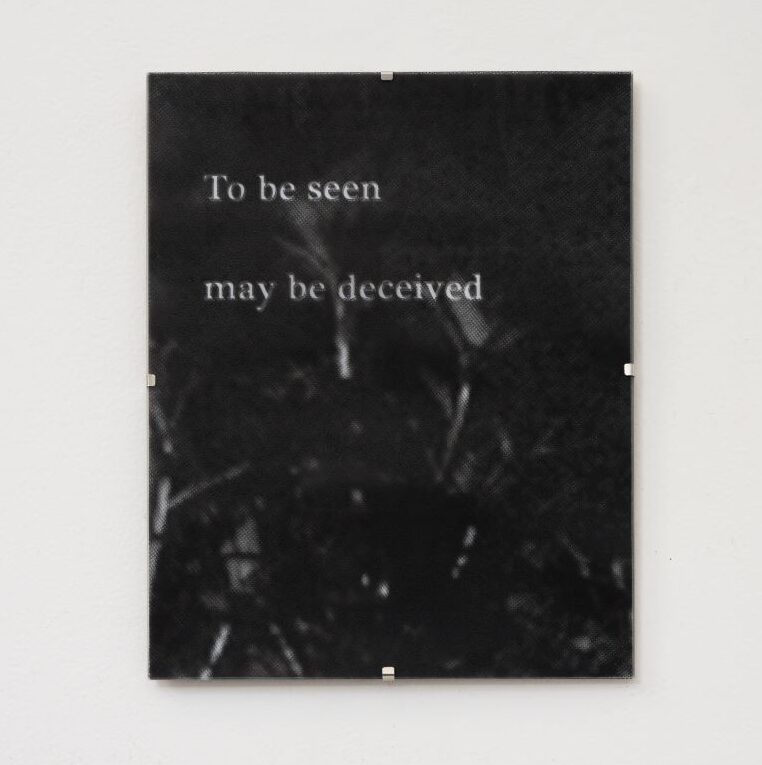

Earlier this year, McKone exhibited first last light, at Baltimore’s Full Circle Gallery. For this exhibition, McKone and artist/historian Alicia Puglionesi worked together to develop ideas around geological time, perception, and how memory is embodied in materials. Puglionesi, who recently published, In Whose Ruins, a book exploring the hidden costs of ruthless economic growth and the myth-making intimately tied to place, produced poetic texts to accompany McKone’s images. In this collaboration, they explored modes of staging photographs to evoke the past of inanimate objects.

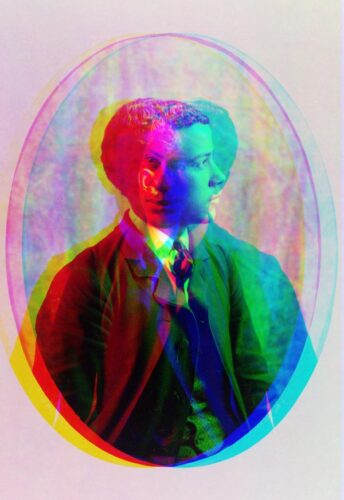

The images of first last light are filled with quiet tension: verdant landscapes laced with otherworldly colors alongside bucolic black and whites of humans merging with land and foliage. When people appear, they seem as elemental to the landscape as the plants and trees and rocks in the frame.

One of McKone’s pieces from first last light is on view through August 12 in Richmond, VA as part of Candela’s Gallery’s annual juried and invitational show UnBound12!