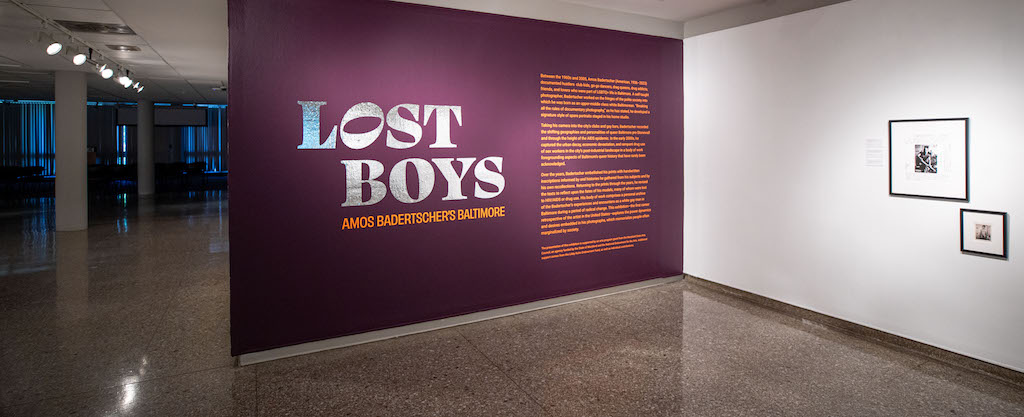

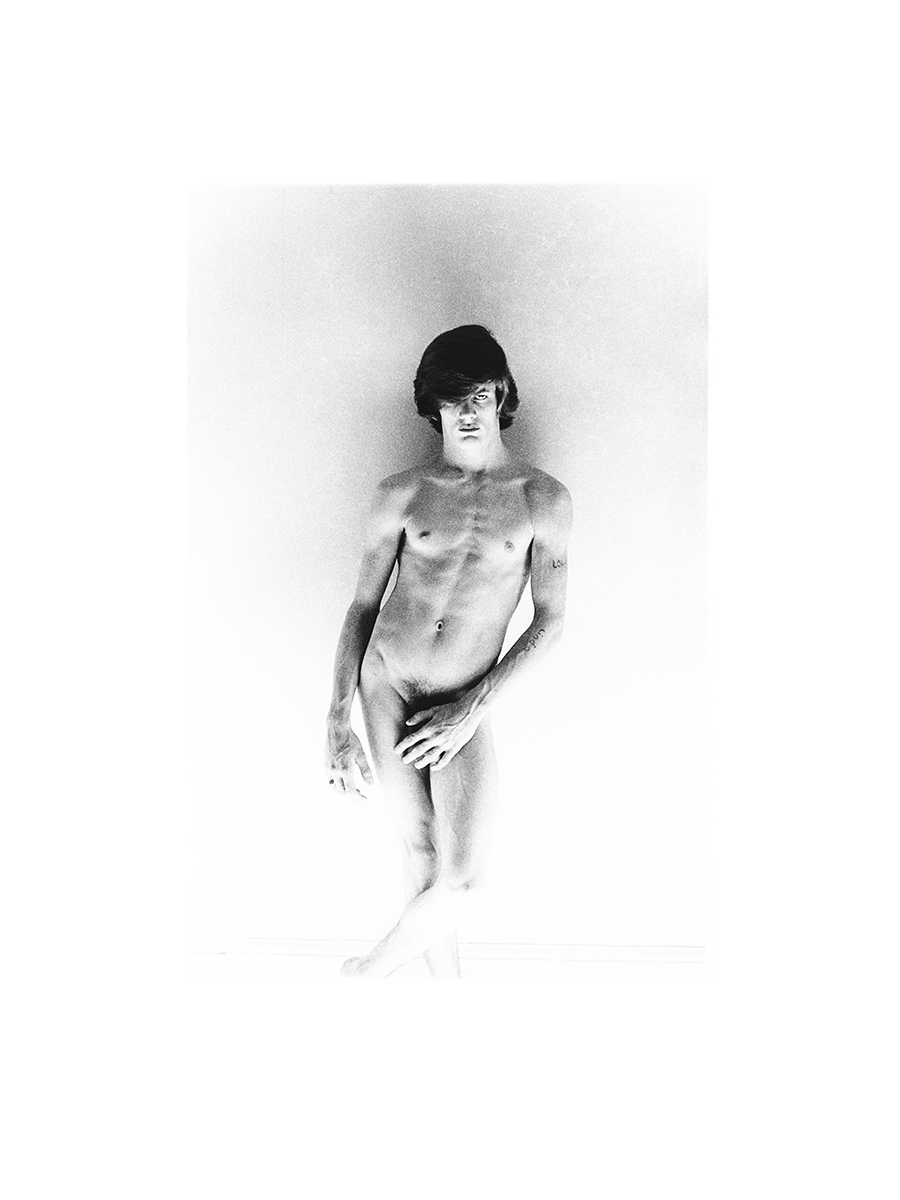

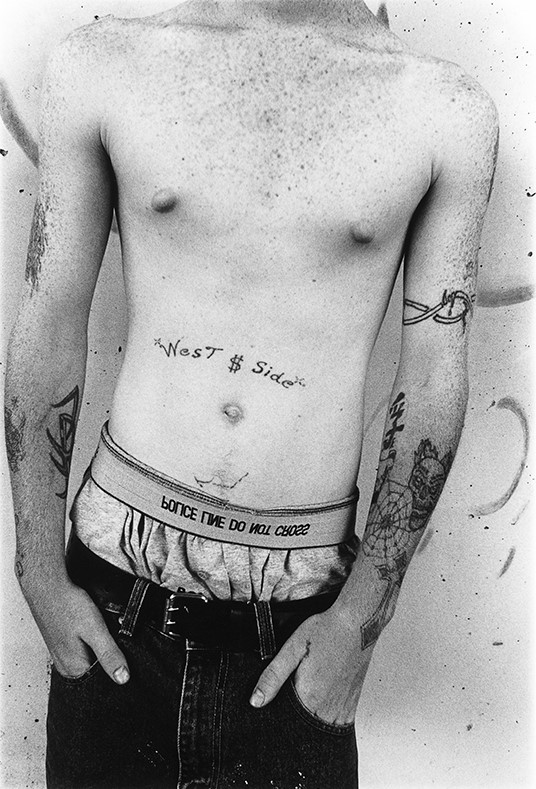

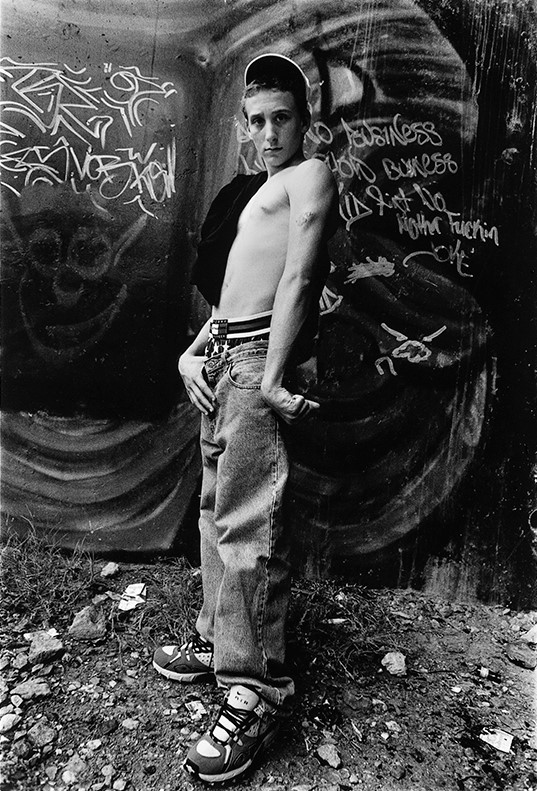

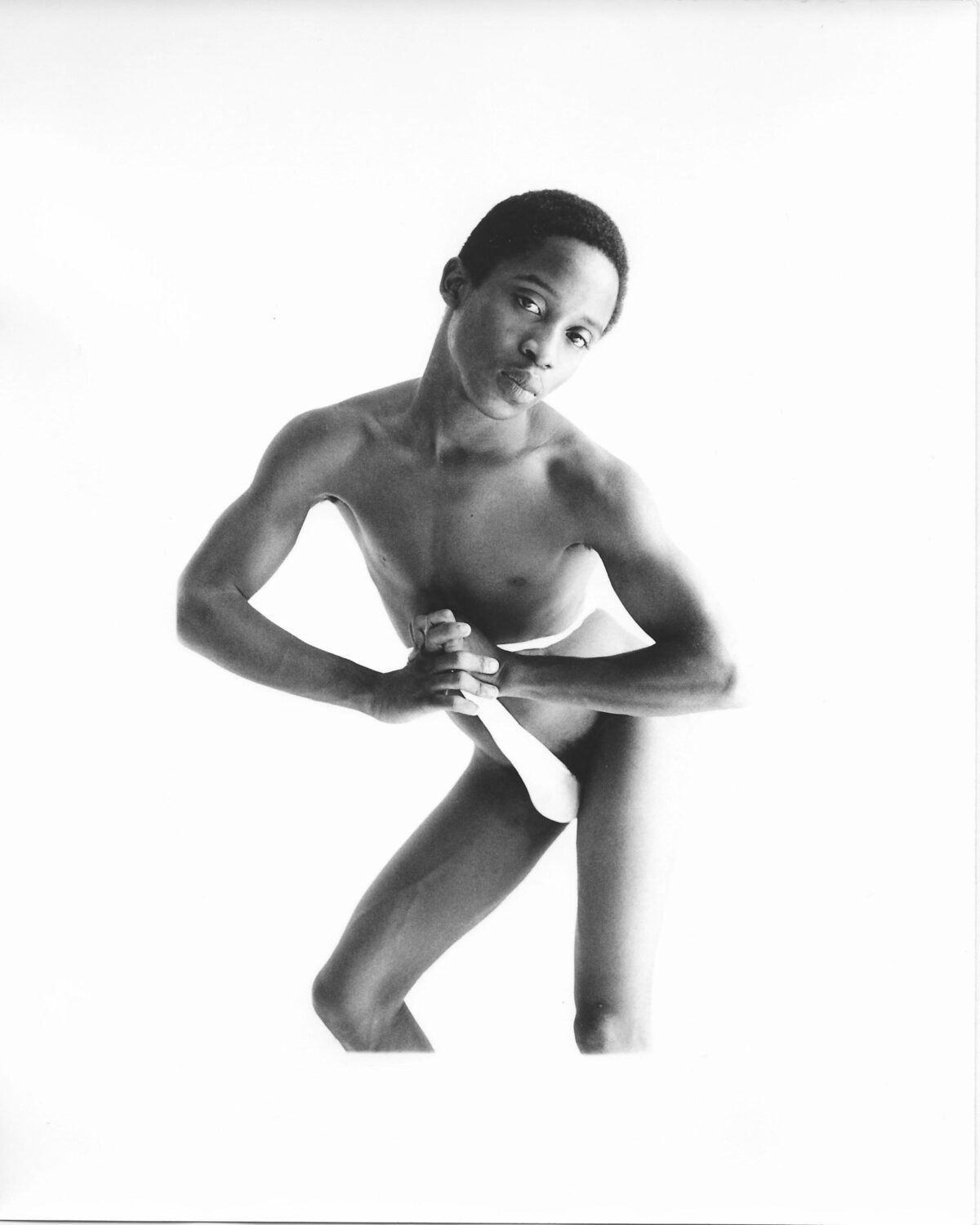

Featuring nearly 200 photographs and extensive accompanying texts, Lost Boys: Amos Badertscher’s Baltimore (in UMBC’s Albin O. Kuhn Gallery, through December 15) is a potent and complex demonstration of one man’s abiding fascination with Charm City’s demimonde. From the 1960s to the early 2000s, Badertscher shot a motley parade of rent boys, homeless gamins, slinky twinks, club kids, and drag queens, many of whom he befriended and then watched with interest over the years.

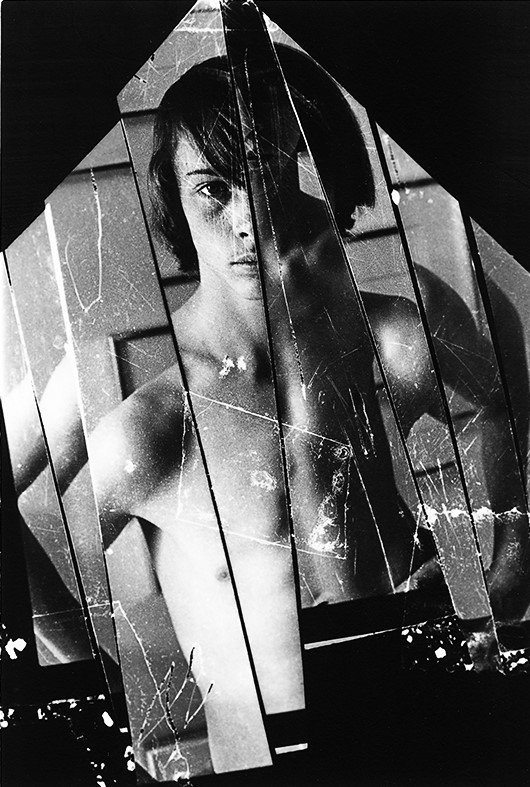

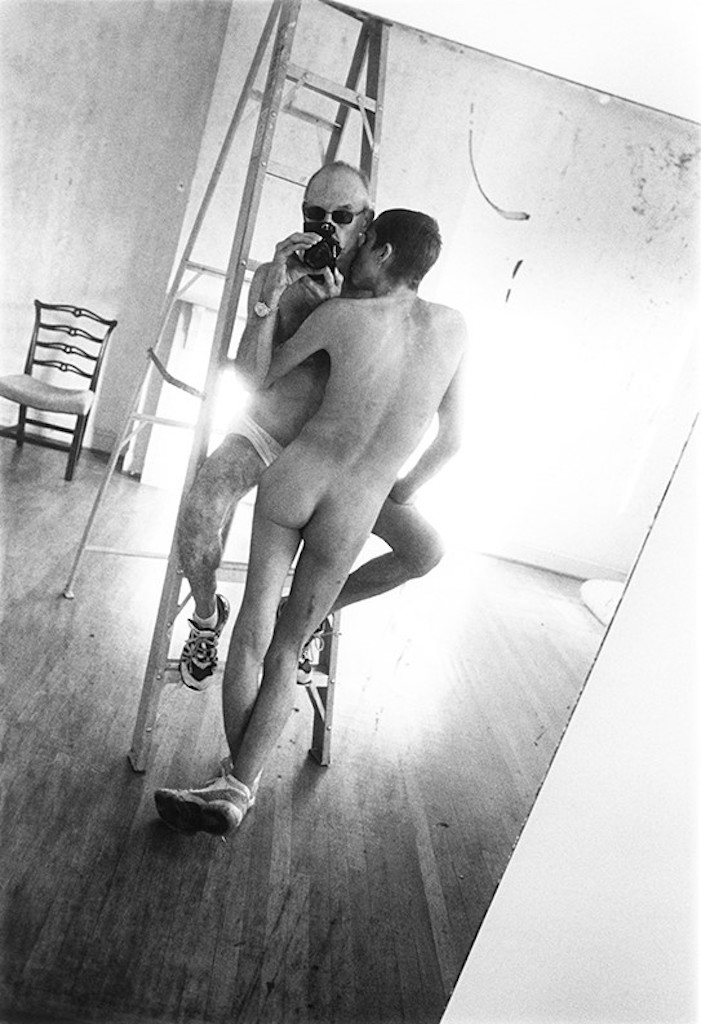

This show, curated by Beth Saunders, offers a thorough and responsible account of his artistic career: a chance to look through the lens of a significant queer portraitist. But it serves, too, as a sexy and spirited challenge to traditional norms, a sympathetic depiction of fringe cultures—and an unresolved exercise in thorny, asymmetrical power dynamics. The result is a diverse, fascinating, and complicated archive.

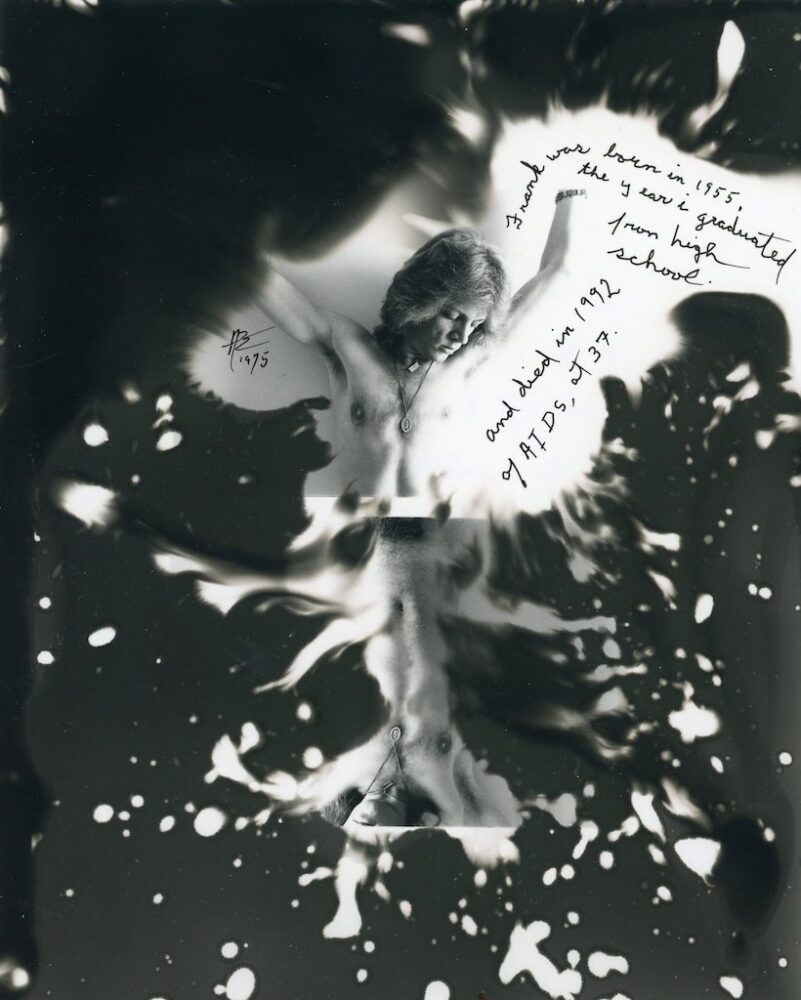

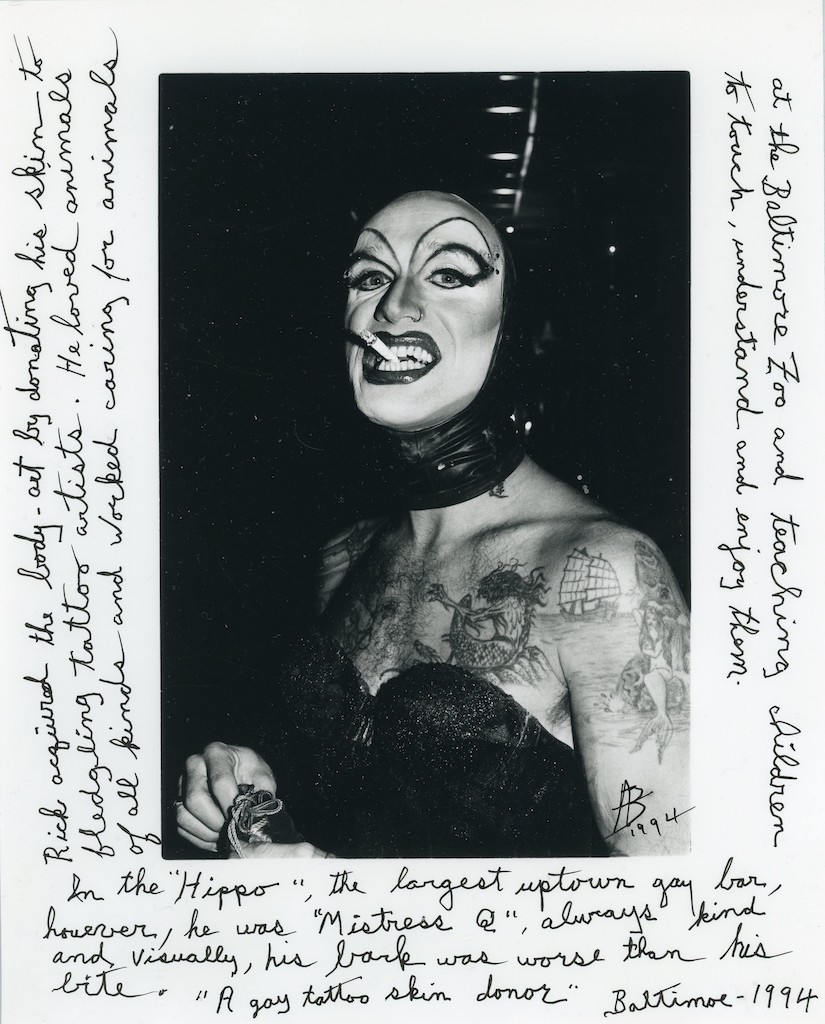

It’s also, in several senses, an elegy. Many of the individuals photographed by Badertscher died young, due to the AIDS epidemic, substance abuse, violence, or societal neglect. In some cases, their biographies are evoked in affecting handwritten accounts that the photographer later added to his prints, or in printed excerpts of conversations between the photographer and Hunter O’Hanian (who served as consulting curator, and who spoke with Badertscher during the planning stages of this show). Those conversations acquired a special resonance in the wake of Badertscher’s death, at the age of 86, this past July. Moreover, several of the gay bars and clubs in which Badertscher met and sometimes shot his subjects—the Hippo; Grand Central; Club Bunns—are now shuttered. This is a show, then, shadowed by loss.

But the predominant tone of the photographs is not melancholy. Rather, it’s a combination of relentless energy and resolute assertiveness. And, as the first career retrospective of Badertscher’s work staged in the U.S., this show offers a compelling case for the historical importance of his work (which was also featured in a 2020 survey at Berlin’s Schwules Museum, and will be on display in a concurrent show opening at Clamp, a Manhattan gallery, on September 14.) Much like Badertscher’s models, who confidently vogue for the camera, Saunders’ exhibit firmly rejects a lengthy history of marginalization.