“What images and thoughts emerge when myths and histories collide?” Lisa Graziose Corrin, a founding curator of Baltimore’s celebrated Contemporary Museum, asked this question to a panel comprising the artists featured in Histories Collide at the BMA earlier this month. The exhibition features Jackie Milad, Nekisha Durrett, and Fred Wilson—whose seminal Baltimore exhibition Mining the Museum Corrin helped organize back in 1992 at the Maryland Historical Society.

The artists were candid about their art practices and shared anecdotes of their lives, even pinpointing moments in time in which their lives previously intersected without their knowledge. As they all shared throughout the night, one main thread remained: the importance of who tells history and how it is shared.

“My works are not endings. They are beginnings,” explained Fred Wilson, “They’re to think about the reframing and rethinking of these histories, why it’s happened, and how they were intersected. But also, how we have changed how those relationships to suit an audience.”

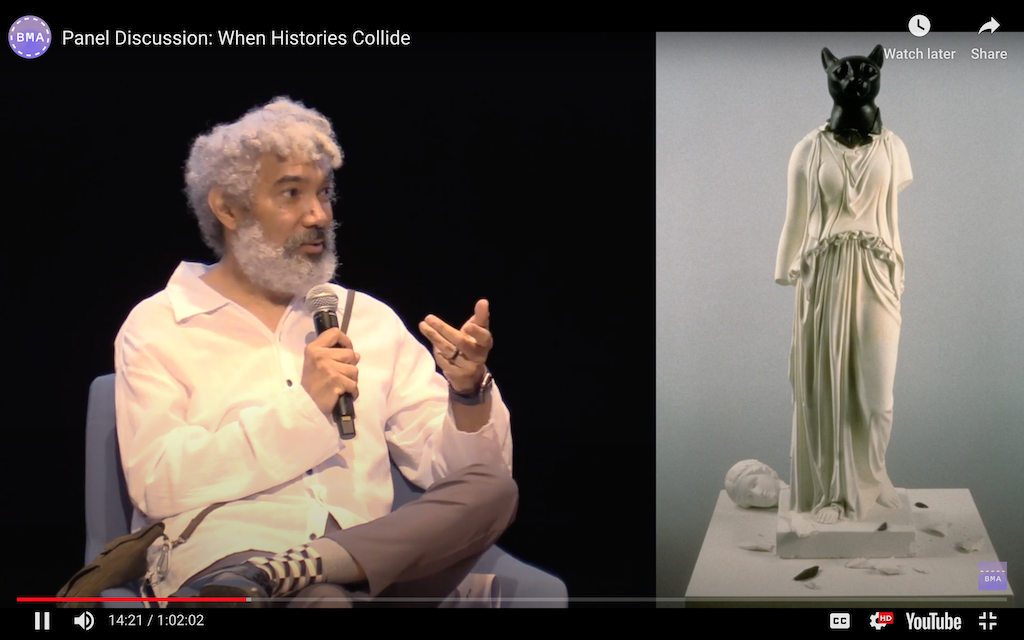

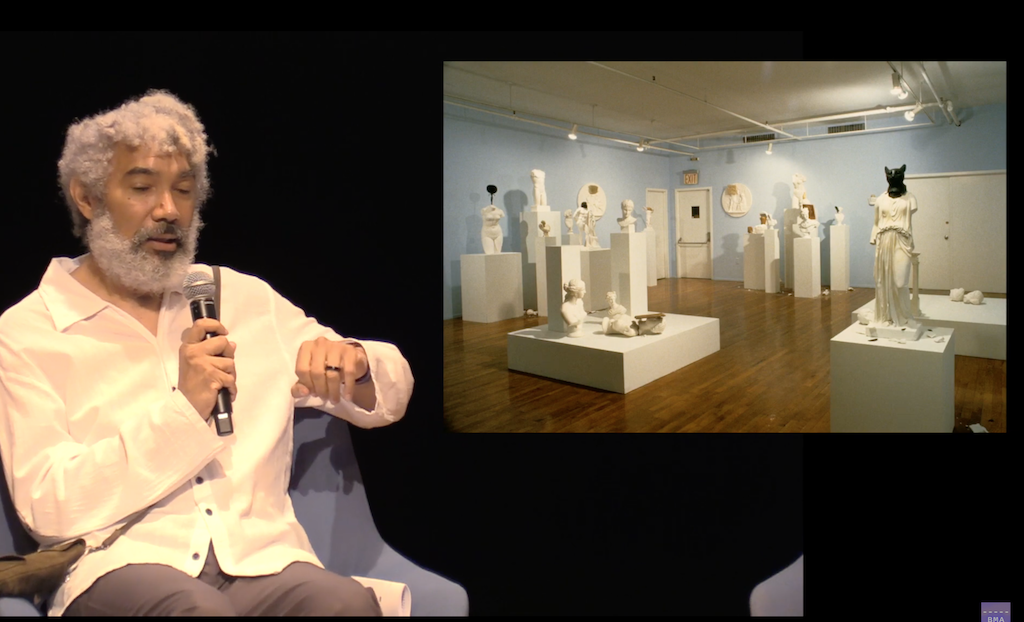

Fred Wilson’s “Artemis/Bast,” centered in the BMA exhibit, embodies the concept of collision between histories and culture and inspired the other two works in the show. The plaster and paint sculpture is composed of two found objects. The lower half is a white figure of Artemis, a Greek goddess, cut off at the neck upon which sits a black feline head of Bast, an Egyptian goddess.

Both deities are associated with the same concepts, including fertility, the moon, and protection of women and children, but their place in history has been largely separate. “Artemis/Bast” does not stop at pointing out the similarities between these two mythological figures, but rather makes a grander statement about the erasure of Africa’s cultural contributions and the whitewashed retelling of the Ancient World through Greek and Roman sculpture.