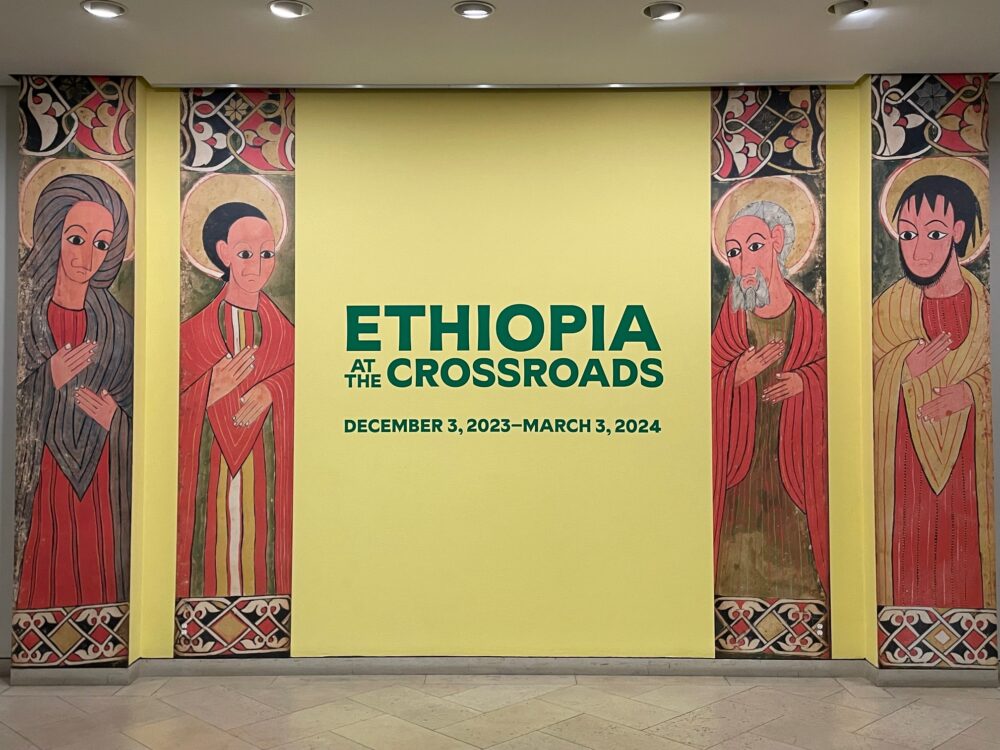

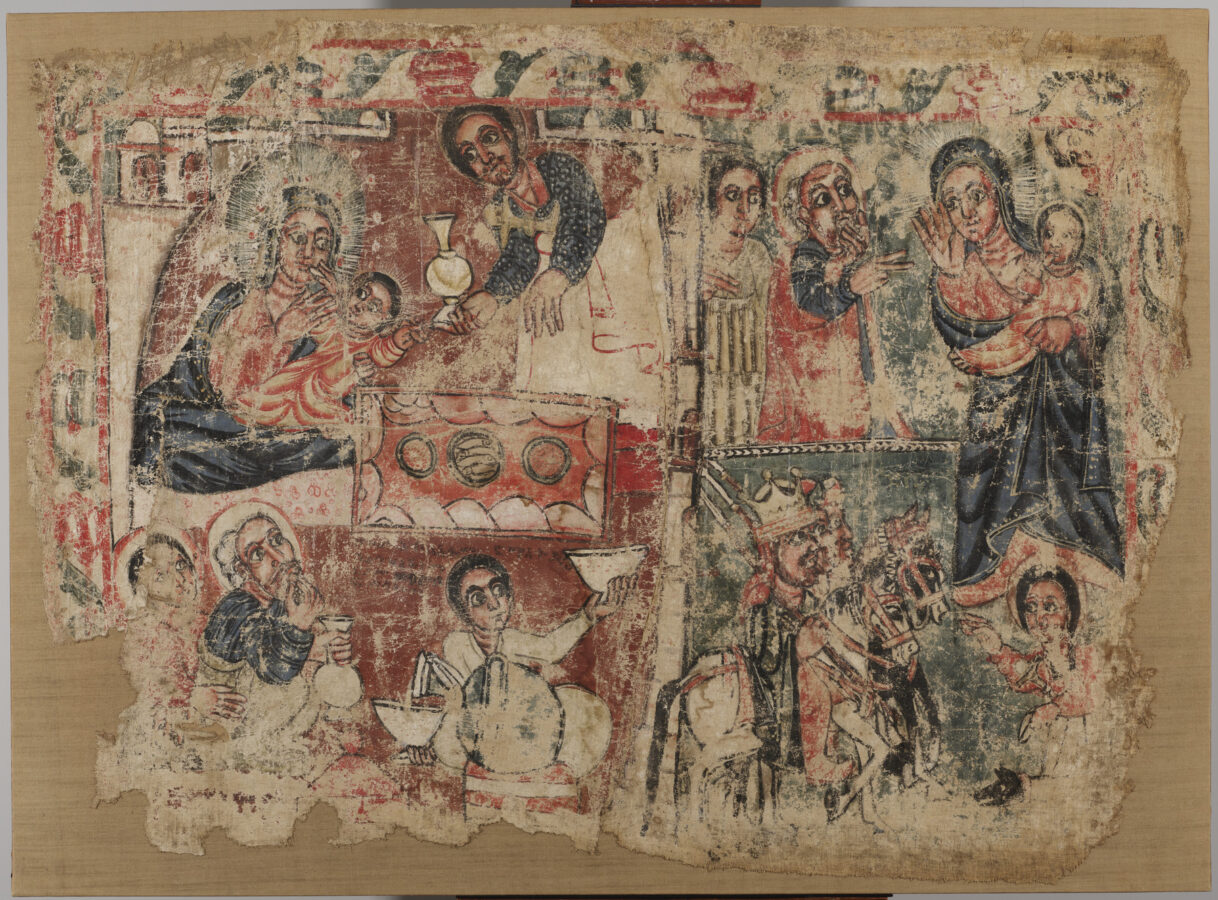

Among the first works in the Walters Art Museum’s recently opened Ethiopia at the Crossroads (through March 3) is a delightful 18th-century canvas mural that depicts, among other things, a rapt Virgin Mary. Wide-eyed, she gestures in demure astonishment as she receives a wafer from her precocious child. But her gaze also wanders towards a handsome vessel gently extended by a priest. Agog, Mary is vibrantly alert to the appeal of material objects—and to the broad implications that lie behind them.

In that sense, she offers a sort of model for those who visit this rich, ambitious exhibition, encouraging us to look for overarching meanings. For instance, the mural points to the centrality of religious art in Ethiopia—which, in addition to being one of the oldest Christian nations, can boast of significant Jewish and Islamic patrimonies. And its formal aspects (thick outlines; bold fields of color; restrained modeling) support, in their vaguely Byzantine aspect, the show’s central claim that Ethiopian art has always been profoundly influenced by regional traditions. Look closely enough, the Virgin’s eyes suggest, and you may begin to see in new ways.

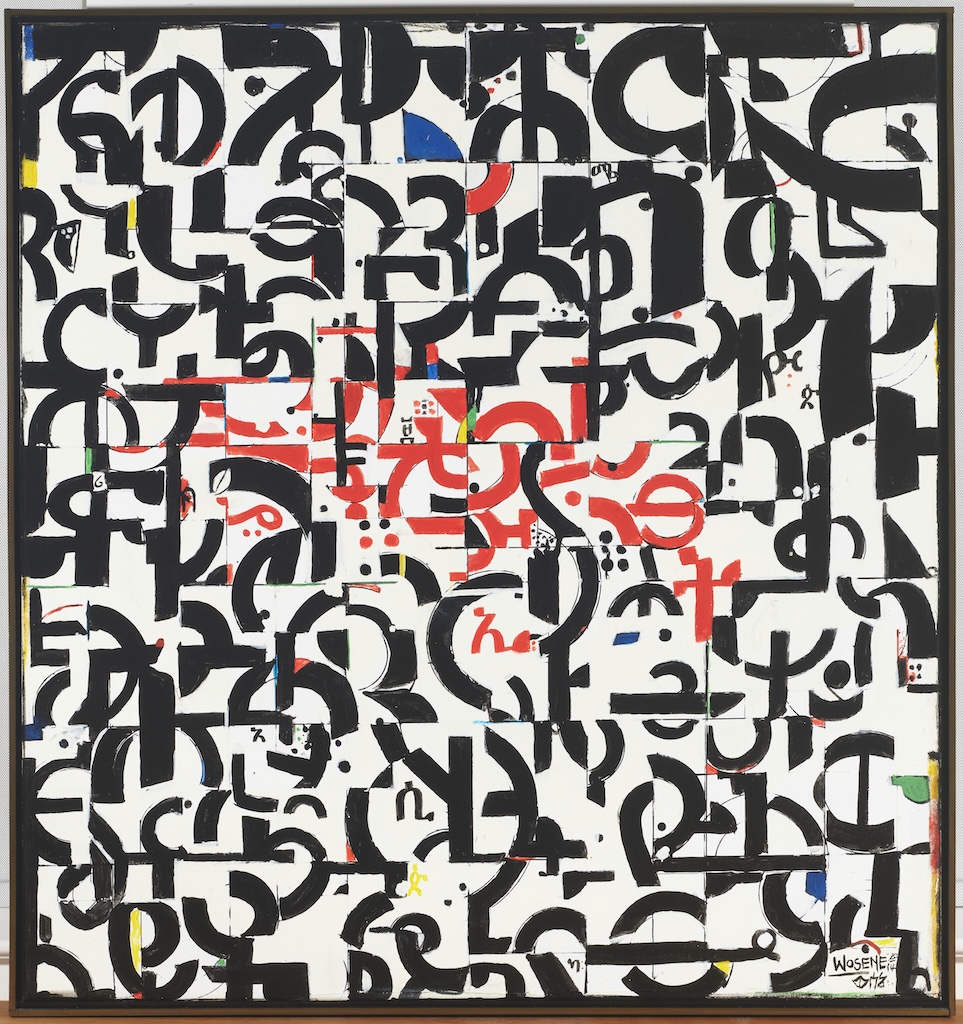

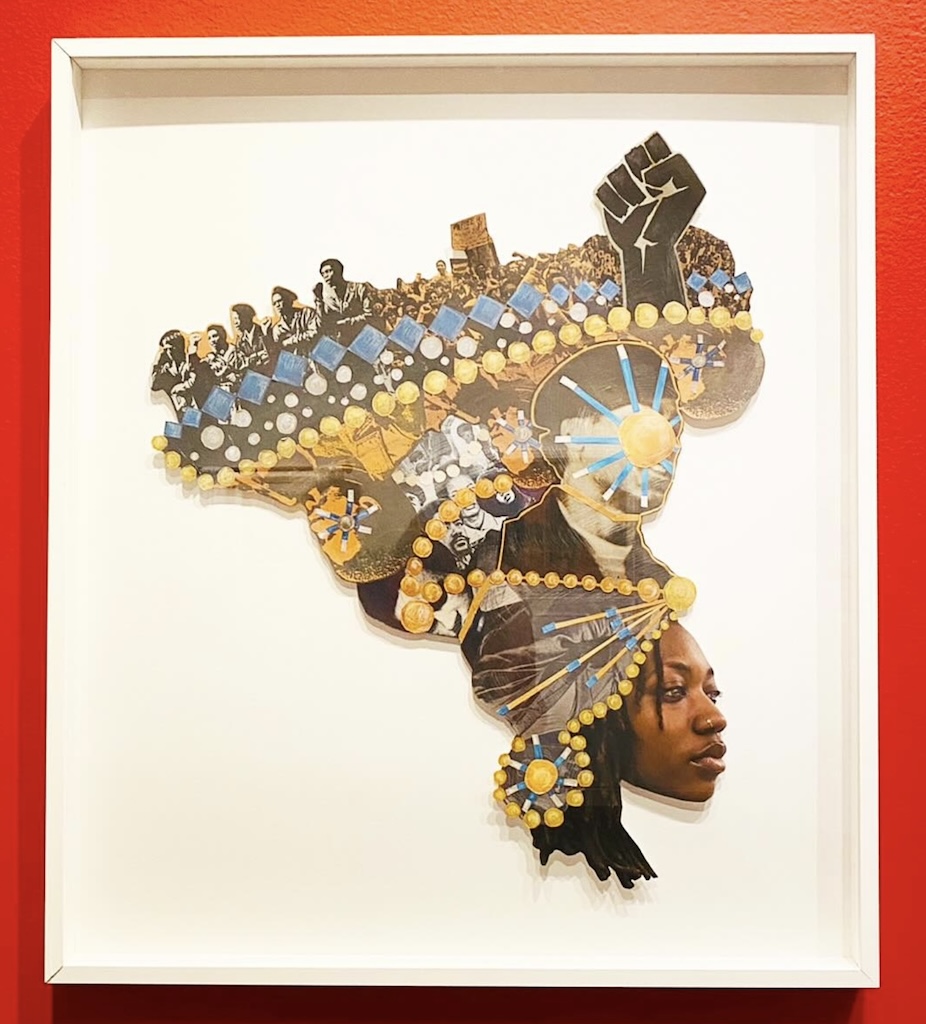

And indeed, you might. While the Walters has been able to boast of one of the strongest collections of Ethiopian art in the world since the 1990s, the current exhibition offers a meaningful attempt to tell a complex and relational visual history in unprecedentedly detailed ways. To that end, curator Christine Sciacca worked with several American and Ethiopian institutions and community groups, and she commissioned Tsedaye Makonnen, a DC-based artist, to address a slate of works by artists in Ethiopia and members of the extensive Ethiopian diaspora. The result is a rewarding show of diverse objects that collectively attest to deep continuities and extensive cultural exchanges.