A final room thus offers a fitting coda. Designed largely by two students in Deyane Moses’ ongoing Exhibition Development Seminar (which includes students from MICA, Morgan State, Coppin State, and Johns Hopkins), the space includes a timeline of Scott’s life and an array of books related to quilting. But it also features a scrapbook, a video, and a number of items from Scott’s 1998 exhibition at MICA, Eyewinkers, Tumbleturds, and Candlebugs, which was curated by Ciscle and the very first cohort of EDS students.

This is thus a chance to reflect on a quarter century of local history—and to look forward to a host of related exhibitions and events that Moses and her class will direct at eight other sites around Baltimore City from February to May 2024.

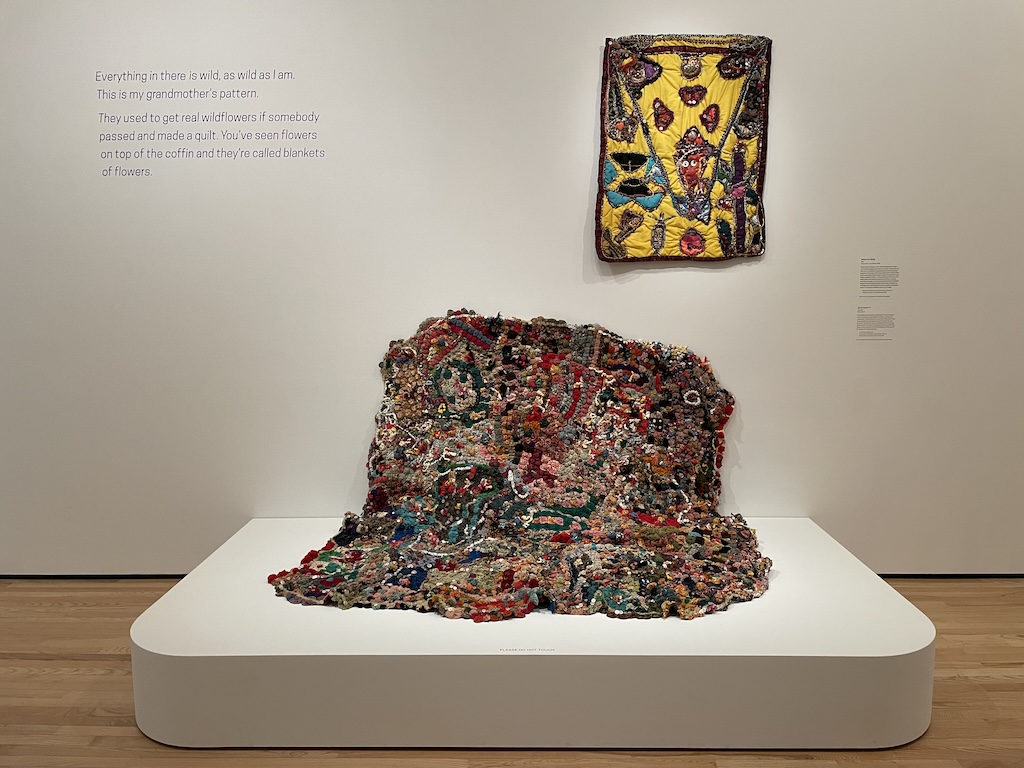

As a result, this is very much a show about community. Study the labels closely, and you’ll discern the outlines of a sprawling social network: an artistic ecosystem in which Scott was a vital nexus. Given that, the BMA’s attempts at truly inclusive exhibition design feel especially apt. Through the provision of multiple entrances, various seating options, braille wall texts and a touchable quilted sample, the museum anticipates the differing needs of a diverse audience, and upholds Scott’s basic interest in affirmation and the irreducible value of each individual.

So how, finally, to think about Scott’s practice? Certainly, it’s possible to see her work as an extension of diasporic traditions and as loosely related to the work of other African-American quilters. The notion of stones charged with potency has a lengthy history in Africa, and Hausa dyers sometimes work stones into bunches of fabric. Sharon Kerry-Harlan occasionally employed buttons and round objects in the 1990s, and the shells and snakeskins that dot Scott’s compositions also appear in the work of Dindga McCannon. These are significant, if limited, continuities.

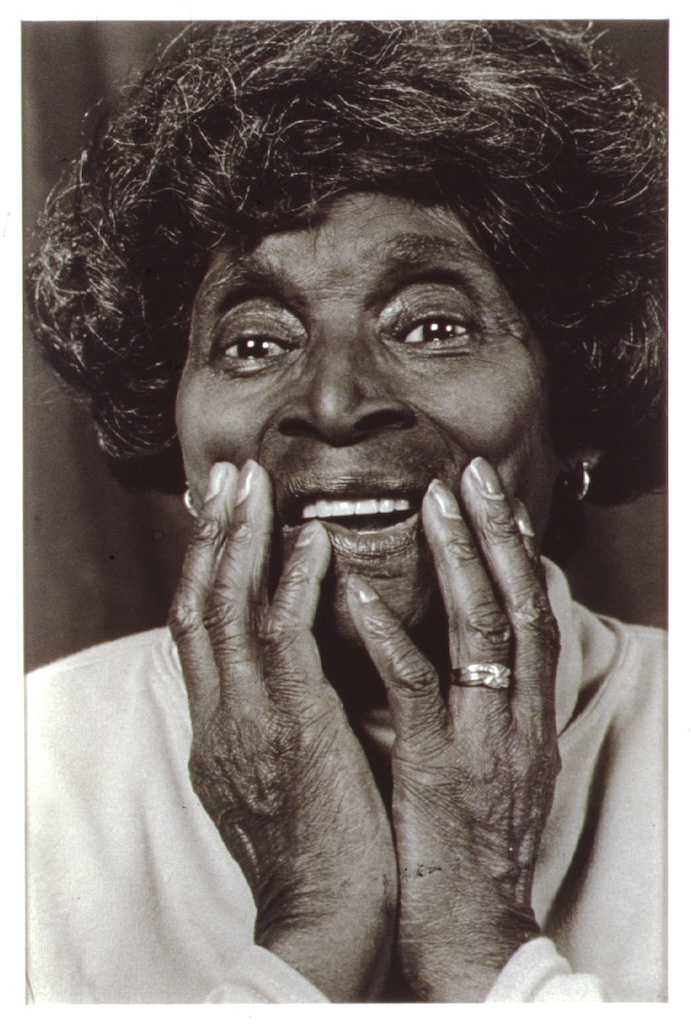

But as the siting of this show implies, it can also be rewarding or even liberating to think of Scott’s work simply as contemporary art. Her recurring use of items with personal histories (one of the quilts on display is made largely of neckties that belonged to a donor’s grandfather) embodies the “archival impulse” that Hal Foster famously discerned in 1990s contemporary artistic circles. And her fluid embrace of multiple mark-making and signifying strategies makes her work a semiotic wonderland. When she was coming up, Scott says in one of the videos, she called herself a quilter—”but now I use the word from the web. I’m an artist.”

She certainly was, and this show clearly conveys her audacious, irrepressible artistry. In the process, it also offers a subtle but insistent disruption of traditional museological and art historical logic, gently expanding our sense of what contemporary art might encompass. After revisiting this show, I found myself thinking about Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz, an iconoclastic 1961 jazz album built around raucous, heterophonic improvisation and featuring, on its cover, a reproduction of a painting by Jackson Pollock.

Arguably, Eyewinkers, Tumbleturds, and Candlebugs involves a comparable energy and a related openness to casual cross-genre connections. Animated by cosmic allusions and personal histories, Scott’s works certainly achieve their soulful aim. But as this show demonstrates, they can also hold their own in conversations about contemporary art. Alluring exercises in stitchwork, they thus hint at what it might mean to tug at the stitches of a history of art that has not always been welcoming to such magic.