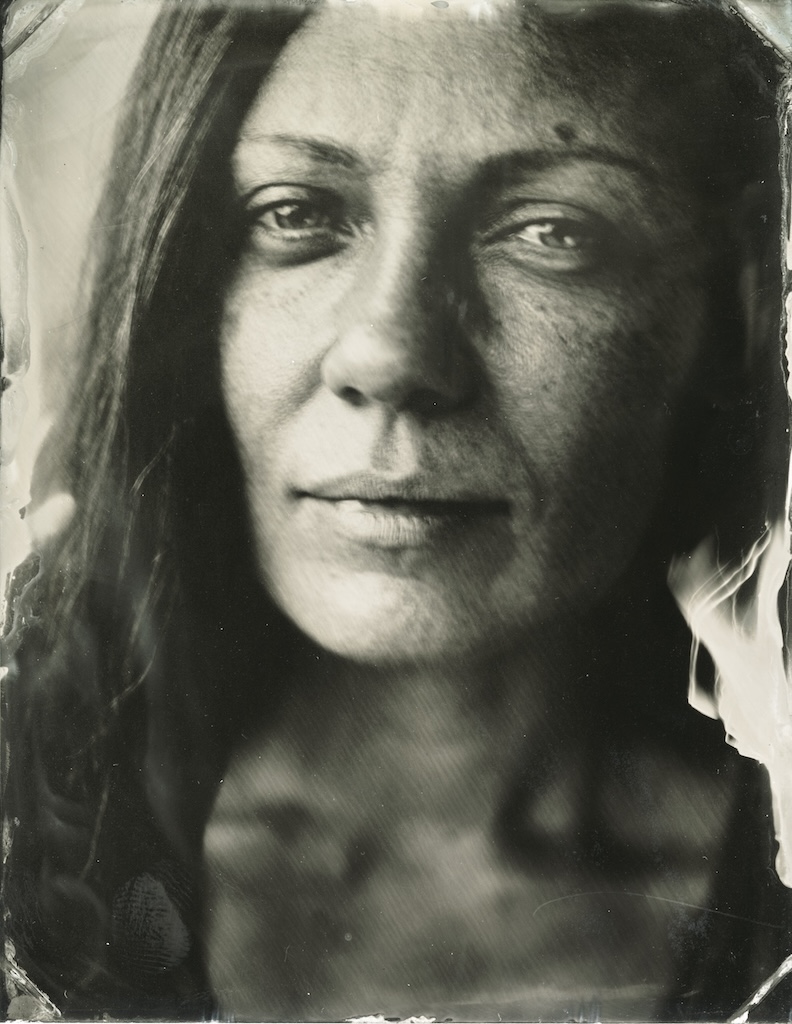

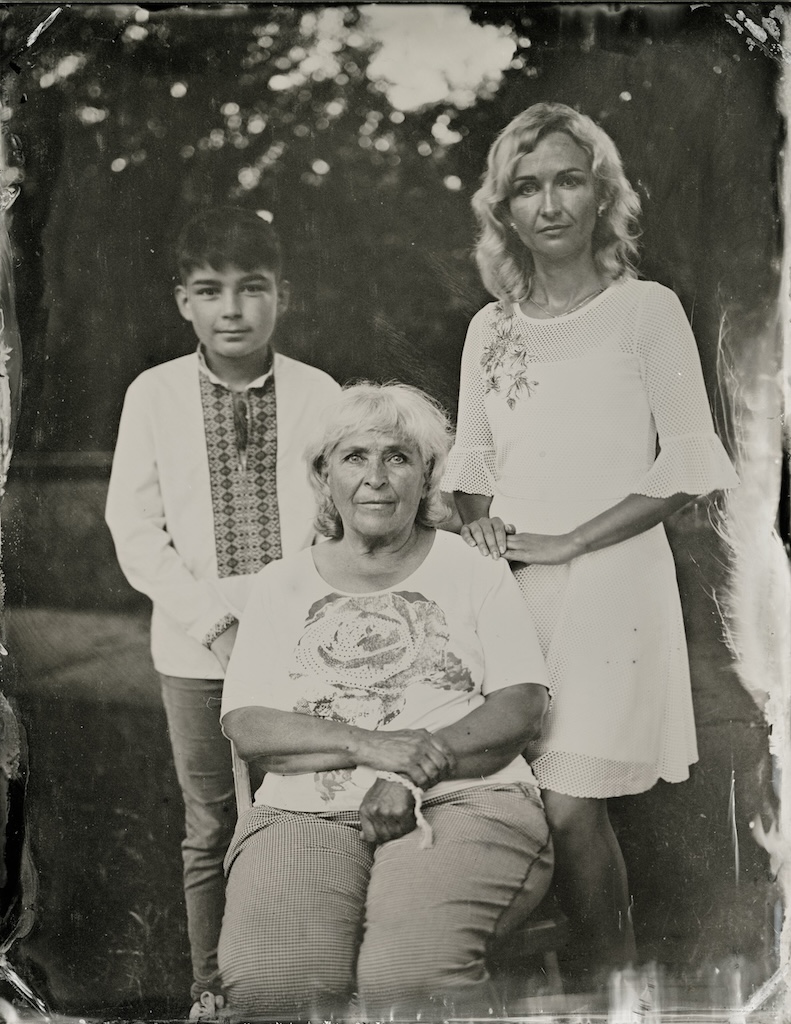

Mirroring the reaction of her sitters, there is a visible ambiguity to the portraits in this series as well. Volkova employs a wet plate tintype process that makes her monochromatic images reflective, the faces difficult to discern depending upon the quality of the exposure and angle at which one holds the plate. Sometimes a frame will look blank and then suddenly a family of four flickers into view, father and son standing, daughter seated in her mother’s lap, all slightly iridescent.

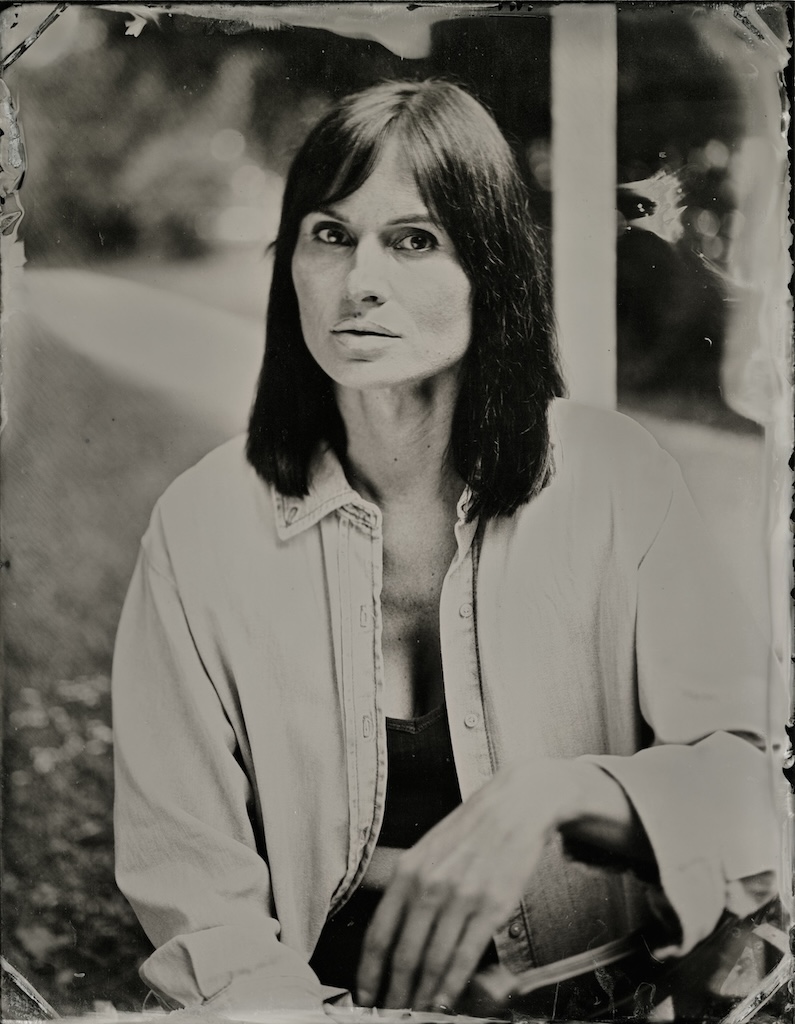

Tintype photography is an old, slow, manual process, most prominent in the mid-1800s. Images are created by exposing thin metal plates coated in a collodion emulsion, a sticky, transparent medium that is soaked in light-sensitive silver nitrate while wet and produces a direct positive image. A great deal of light is required for this process, and, as a result, exposure times are much longer than a typical photograph. The smallest movement in front of the camera—like the distracted head of a child—results in a blur.

There is an interesting juxtaposition between the medium of tintype and the subject of refugees. Volkova’s project aims to fix, however momentarily, a population defined by movement—people dislocated by war. They live in a state of suspension as the violence continues and the future remains uncertain. At the same time, the portrait sitters are engaged in the act of preserving this moment of fluidity. In most of these images, time is rendered multifaceted; though the context is one of extreme conflict, the people are most often choosing to represent themselves in a moment of empowerment, love, contentment, or joy. In one, a woman theatrically holds a ringed finger to her lips, staring askance at the viewer, as if she knows the next move is hers to make.

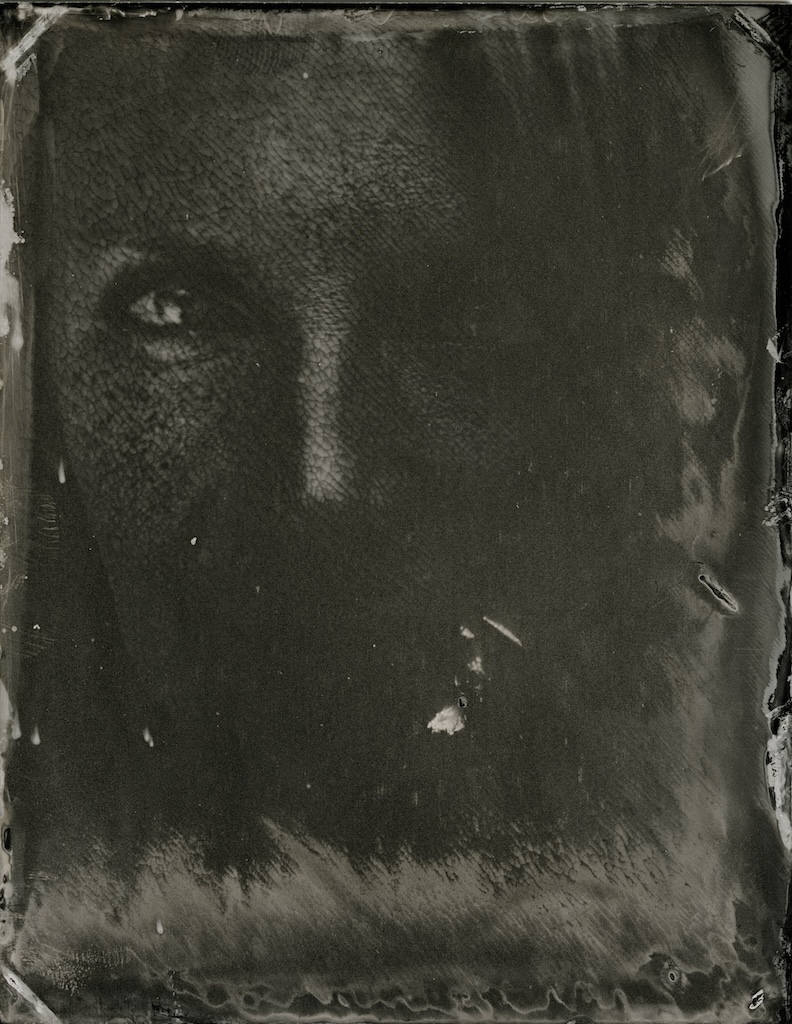

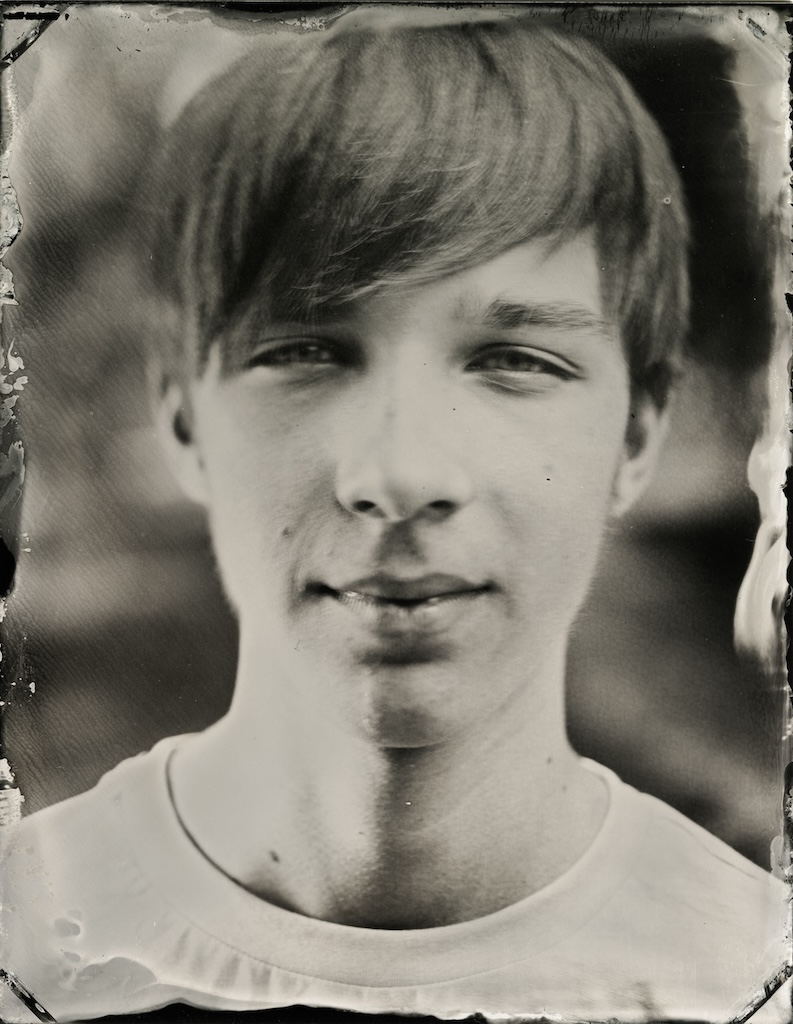

Volkova describes tintype as a medium in which an artist must let go of attachments to mastery because there are so many factors beyond control. Using volatile outdoor light, subtle shadows can quickly become dark and deep. Since she is collaborating with her subjects, she also needs to study a person’s nuances while navigating each fresh social circumstance: two lovers with their eyes closed, faces touching; a boy somewhere between smirk and smile; a woman shaking her head back and forth. There is no way to preview a tintype, nor can it be duplicated. The medium captures every success and failure with equal permanency, the irreplicable moment’s banalities and exceptionalities archived on a metal plate.

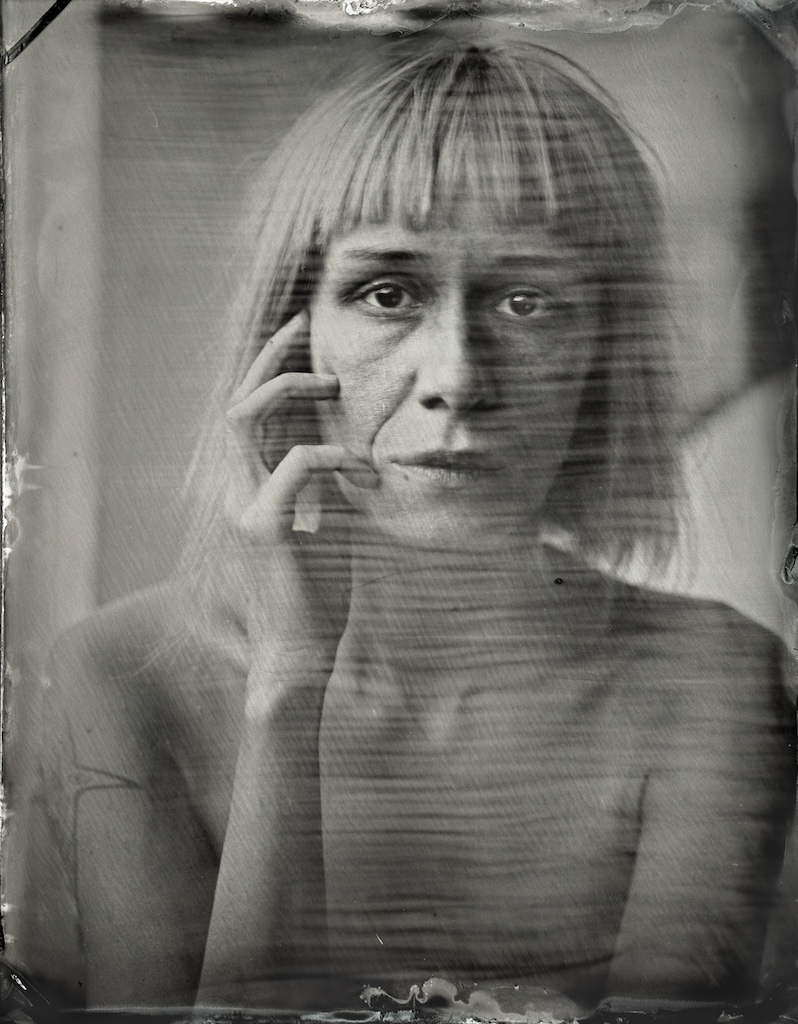

In the heat of summer in Stuttgart, Augsburg, and Berlin, the wet plates were drying more quickly than the images could develop, leaving behind milky white streaks. These ethereal waves and ripples—what some might call a mistake but what Volkova terms an “artifact”—make some of the portraits look ghostly, as though one is peering through a veil to another world. An aura laps at one woman’s hair; another young woman stares at a white apparition; one couple looks as though their faces are pressed to the folds of a sheer curtain.

At times, these “artifacts” also function as negative space in the image, an outcome with a significance on which Volkova is still reflecting. They bring an element of emptiness to each portrait—a genre that is ostensibly all about presence. Considering the subjects are refugees in a war that is still very much present, these people might be considered both literally and figuratively within a negative space. If to negate is to counteract, then the space these refugees (and consequently these portraits) occupy is indeed a negative one: a space sought out in reaction, a defensive measure. Thought of in this way, the negative space might be preferable for now, if not yet positive.