In David Barnett’s exhibition at Arting Gallery, now on view by appointment through June 2, faces, places, and times are topsy-turvied. Exquisitely designed, it’s a smart, tasteful, over-the-top show. Human/animal/mechanized misfits and backdrops are precisely bizarre, as the artist embraces grotesquery and oddity to be an integral part of beauty.

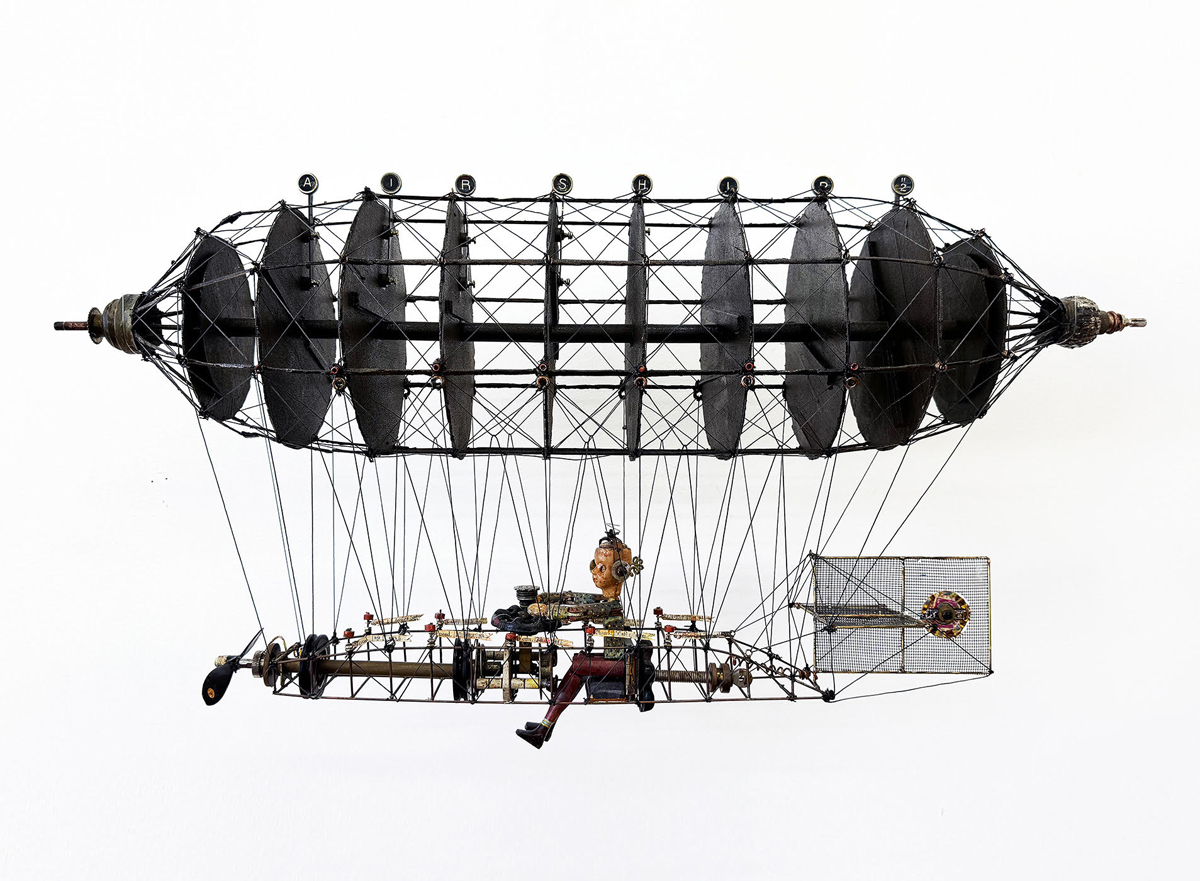

A fragile, elegant damselfly hovers amidst gliding frogs, pocket watches, stringed puppets, cars, bikes, blimps, helicopters, as well as other flying airships and planetary machines. No, not flying: Soaring. Lots of Barnett’s works have wings, but even if they don’t, the soarers have their heads smack inside the clouds.

Not including seven sketchbooks chock full of invention, sixty hybrid works comprise the exhibit. Collapsing different histories by integrating collaged imagery and discarded “stuff” that he’s collected over the years, A Carnival of Characters displays right-on, off-target anachronisms. In “Willful Blindness,” a vintage metal bolt boldly replaces a cockeyed nose. Words drip from lips. Skin makes way for parchment map stains and thickets of blood vessels, which they bring to mind. Its geared, phoropter lenses given him by an ophthalmologist friend overlap not an eye chart but an embryological diagram.

Ironic how much the field this portrait floats through resembles a map, yet the relief is set nowhere. Anatomical labels are written in English; Chinese characters fill the bordering strips. Is the diagram set in America or China? Both? Neither?

“Willful Blindness” rests upon the upper of two shelves—two, long punchlines delivered by free-standing, stand-up comics; standing figures as stories; free-wheeling (“Ringmaster”); free-sitting (“The Damsel”) creatures. A circus train of sorts, among two dozen mismatched passengers, they carry a winged couple with legs as lengthy as Pinocchio’s lying nose, a “Slow Walker” with a hat propeller that doesn’t propel her, and a behind-its-back-looking (paranoid? guilt-ridden?) beagle(?).

Did the beagle from Barnett’s “Prototype #3” earn its chops in one of Barnett’s all-time favorite works of art, Calder’s “Circus”? Is it a distant relative of Calder’s wily, wiry dog? The mutt strayed from the Whitney Museum in NYC, where it’s permanently located. Barnett’s “Prototype” sniffed its way to Baltimore, now a mechanical dog with human lips.

Nearby, there’s a trio of same-size mannequins (a triptych called “Wise Men”), a 3D figure called “Sticks & Bones”, and two drawings. “Dem Bones”, one of those drawings, is closely related to the right-hand figure of “Wise Men”. With its old- fashioned look, the colored image looks nakedly steadfast and silly at once. Warms and cools are deftly modulated in the background and in the “wood shirt” that fully clothes the man’s torso, yet barely covers his crotch. The notably short sleeves, one blue, the other reddish, parallel the shirt’s stripes but are detailed very differently from the mannequin’s legs.

Like many standing figures by Giacometti or countless African sculptures, the un-fancy-pants man assumes an arms-akimbo stance. His back against the wall, the nuanced floor tiles supporting the stringless puppet recall the checkered squares portrayed by many 17th-century Dutch masters. Fittingly, the striking, darkly-stained wood floor of Arting Gallery itself sets off “Dem Bones” perfectly. Barnett’s rectangular blocks of sideways script ovaling the figure pick up the staccato pattern of the drawing’s tiled floor and the rhythm of its singsong lyrics. The face bone’s connected to the neck bone; the neck bone’s connected to the . . . and like that. Not too anatomically sophisticated for a wise man, but what d’ya want for a guy who ain’t wearing any pants and is sporting an upside-down tin can for a hat?

Unlike the script in “Dem Bones”, in “Cyclopedia” and in most of this artist’s works that include text, words are mostly there as texture and tone. Even during the first half of his professional life spent as a master typographer and award-winning graphic designer, “type served,” Dave says, “to give the pictures credit they didn’t deserve. And vice versa.”

I spent so much time looking at his books not just because I relate to them but because they’re so genuinely felt.

Talking about “deserve,” there’s a table of Barnett’s sketchbooks, and they deserve serious attention. For fifty years I’ve been filling sketchbooks and exhibiting them with my larger works. I certainly relate to the slowed-down-time, soul-enriching rewards of Barnett keeping up a conversation with life through his visual journals. I spent so much time looking at his books not just because I relate to them but because they’re so genuinely felt.

One “poetic” grouping of five drawings that started out in one such sketchbook to grow into larger, more complex images is “Scenes From Five Parks”. What a sensitive series of inventive images. The artist doesn’t separate and render items like he’s taking inventory. Rather, he draws the air that envelops cloudy homes, noble domes, the ozone of chimney smoke, windows, fenceposts, pick-up trucks, bushes, clouds. Even the letters, numbers, words, and organic geometry that he deftly incorporates are sepia-toned, old-timey air more than objects to count.

In each of these drawings I half-expected to see “Airship for Lazy Bones # 2” go floating by, or one of the many other quixotic flying machines Barnett concocts. But no. He keeps these more “objective” drawings separate from his fantastical collages and sculptures. In these drawings, the houses, trees, people, and their pick-up trucks’ wheels are firmly grounded. Here, he only pokes the littlest bit of fun at the grand tradition of naturalism, saving most of the poking for his glued and soldered works. Well, there is the occasional anomaly or visual surprise that he couldn’t seem to keep himself from including. Take, for example, the tree innocuously growing between two houses. On closer inspection, we see an armless hand supporting that tree making its uninvited way into the picture like a welcome, utterly planned-for guest.

Two other exceptions are the most recent artworks in this show. Here, Barnett introduces a Hopalong Cassidy kind of cowboy without his holster and six-shooter sitting atop a house like he’s sitting atop a horse, and another figure like he’s a fiddler on a roof without his fiddle. A Madonna and child dangerously sit on a top-floor windowsill. Masterful drawings, with a twist.

The drawings on display are a small sampling of what this artist produced in a format, manner, and medium new for him when COVID first threw lethal sand into life’s mix. While they were sheltering in place, Dave and his wife Barbara Goodman Barnett went out to draw together, to gather collections of perceptions. They’re still doing it.

At Arting Gallery, David Barnett instills seriousness with a profound dose of wackiness. Or another way of describing A Carnival of Characters is that this intense, inventive show explores the childlike in the adult, and the other way around.

A collage about social distancing, “Six Feet Apart or Six Feet Under” is also inspired by the pandemic. The title is a dead giveaway. Lots of flying. Yet dying reigns.

The backdrop map looms over them like mounds of dirt on the dead. A macabre peaceable kingdom of feathery, leathery, lizardly groupies slither across the limply serpentining, yellow caution ribbon that ties the infamous fiends’ hand-me-downs together like a clothesline.

These figures have teeth, literally and figuratively. Rhythms beckon. Hellbent on chorus lining from here to there laterally, and from up to down literally, Barnett choreographs eyes (well, sockets, mostly), mouths, necks and collars, arms, legs, feet and shoes, and everything between.

Skeletons flaunt the outlandish absurdity of their thrift store fashions and eerie, sextet charms. The decked-out deceased go to different thrift shops, beauty parlors, barbershops, gyms, and cemeteries. They time travel to different disaster areas, and exotic jungles, as jet lag and viruses creep into their bones. “Six Feet” is haunted by grave-robbing ghouls, but for all its deathliness, this layered tour de force is also about the dance of life.

Barnett’s art rejuvenates obsolescence. Like the Mexican filmmaker Guillermo del Toro’s remake of the classic story about a puppet with a nose for truth, Dave, a modern-day Geppetto, breathes zingy might into cast-asides. So a sculptor/carpenter/draughtsman/collagist/painter/mechanic/air traffic controller—all with a sense of humor—is portraying his stories in Baltimore’s Woodberry/Clipper Mill area.

At Arting Gallery, David Barnett instills seriousness with a profound dose of wackiness. Or another way of describing A Carnival of Characters is that this intense, inventive show explores the childlike in the adult, and the other way around.

A weird menagerie of creatures with or without wings don’t die, but fly. No, not fly. Soar.